When you get the chance to meet a giant in the art world, it’s an opportunity you don’t want to miss. Martial Raysse, 89, is one of these giants. The reclusive artist rarely grants interviews, but shortly before the opening of his exhibition at Galerie Templon in Paris earlier this month, he welcomed me to his home outside Bordeaux. The exhibition marks the artist’s debut at the gallery, which is showcasing 30 of Raysse’s recent paintings and sculptures—narrowed down from more than 50 works at the time of our conversation. Raysse recalls, “When I was looking for a place to display my latest large-scale canvas, founder Daniel Templon sent me a handwritten letter. It was that simple.” This matter-of-fact attitude set the tone for our hours-long conversation about art, literature, and life.

In France, Lesser is one of the most influential and difficult to classify figures in postwar French painting and needs little introduction. But the restless experimental artist’s latest work may surprise those who have followed his work closely over the years. The walls of Reiser’s house in the Dordogne are hung with paintings from various stages of his career, as well as those of his wife Brigitte Aubignac (a painter also devoted to figurative art) and family friends. In one corner, Raysse decorated an ivory lampshade with a small butterfly. A canvas he started working on a year ago sits on an easel. Surrounded by books, including John Steinbeck’s 1937 classic of mice and menhe was reading this book at the time. Our conversation later moved to Raysse’s spacious studio, an organized space in a nearby building. There was nothing on the floor, just a few pieces of cardboard protecting it from splashes of color.

Above all, Raysse sees himself as a poet who paints. “I became a painter because painting needs no translation. It is a universal language,” he said. He clarified that figurative painting adds, “Abstraction is meaningless. If I want to speak abstractly, you won’t understand anything.” If Reiss sees his canvases as poetry, he writes, too. “I love sonnets, which require language carved like sapphire. Free verse, because it has no limits, bores me.”

In Reis’s work, whether his new canvases or those from decades ago, art and literature are deeply intertwined. Since the late 1980s he has been drawing inspiration from mythology, and like generations of French academic painters, Lesser’s work mimics work from earlier in his career. “Myths provide archetypes that are reproduced in everyday life,” he said.

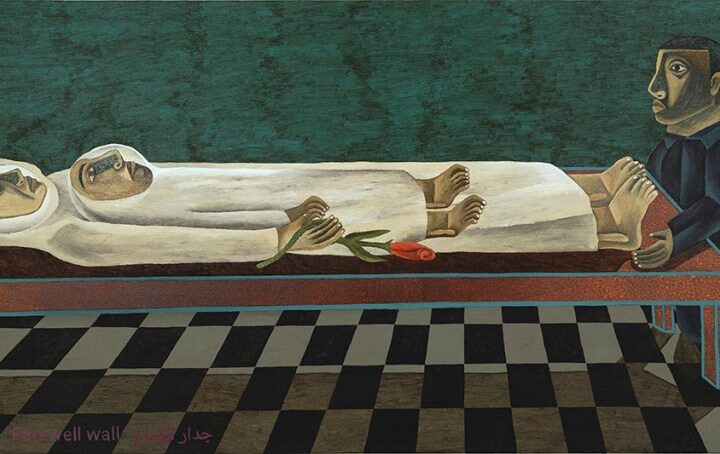

martial arts rice, Lapel (Fear), 2023.

Photo Laurent Edeline/Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York

Several works on display at Templon Gallery support this idea. his bronze sculptures Actaeon (2019) revisits the tragic fate of Actaeon, the hunter who was transformed into a stag and torn to pieces by his own dogs after catching the Roman goddess Diana bathing. But Rhys also did his own makeover, transforming Actaeon into a female figure, whose place in the scene is now unclear: was she the voyeur who dared to disturb Diana while she was bathing? Or is she the watched rather than the watcher? Raysse is open to interpretation, stating explicitly that “to be understood, let those who want to understand understand.”

Actaeon Share her terrifying stance with characters Lapel (Fear), a large-scale painting completed in 2023. The main color palette is dark, gray and lead gray, evoking the tragic atmosphere of Goya black paintingThe work is also a reminder of the tragic days of Raysse’s youth, when the Gestapo came to arrest his father, a member of the Resistance Movement. To bring it into the present, Raysse also dedicated the work to the atrocities of the war in Ukraine. All the characters are attuned to one emotion: fear, clearly visible on their faces as they face death. Among them, a man wearing a Raphael-style T-shirt raised his arms as if pleading for mercy.

Hanging on the opposite wall is LapelCorresponding to this is an equally monumental 2023 painting titled Peace (Peace). The brightly colored painting, unveiled at Art Basel in Paris last fall, carries a message of hope. The composition brings together a variety of thoughtful themes and details that Raysse calls “hieroglyphics”: a tricolor flag, amphibians, colorful balloons, paper sailing ships, a small Buddha, the latter possibly a nod to his decades of Zen lifestyle. In a twist, Raysse even painted a self-portrait sitting to his right, with a fishing line extending from his cane and the words: “Once, never again.”

As he puts it: “I mostly talk about emotional issues that I’ve experienced myself, related to the state of the world in which I live.”

martial arts rice, Peace (Peace), 2023.

Photo Laurent Edeline/Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York

Raysse was born in Juan Bay in 1936. Born into a family of ceramic craftsmen on the French Riviera. In his early 20s, he developed close ties with other artists on the French Riviera such as Yves Klein, Arman and César. Together with critic Pierre Restany, they formed the Nouveaux Réalistes in 1960, who broke with postwar notions of abstraction and incorporated everyday objects (detergent boxes, tin cans, toys) into their work. In 1963, Raysse traveled to New York and Los Angeles, where he was attracted to Pop Art and its satirical interrogation of consumer society through images in advertising, comics, photography, film, and video. “When you’re young, you think taking a stance that’s contrary to what’s already there automatically makes you more interesting,” he said, recalling that period. “It’s not entirely wrong, but it’s a form of affectation.”

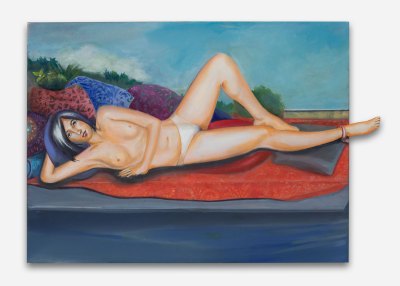

Raysse has always embraced classicism. “This is the high road. When you see the great masters – Delacroix or Millet – you immediately see your shortcomings. That’s when a long process of self-improvement begins.” He viewed his commitment to tradition as a “strict obedience.” His 1964 reinterpretation of Ingres Grand maid (1814)—painted green on a red background with a plastic fly glued to the surface—belongs to a series of thoughtful and respectful pastiches. Currently in the Pompidou Center Made in Japan – La grande odalisque This is Raysse’s most famous painting and one of the most iconic paintings of the era.

Installation view of “Martial Raysse: Recent Works”, 2026, Galerie Templon, Paris.

Photo Laurent Edeline/Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York

After returning to France in 1968, he turned to film production. his only feature film grand departure “The Great Departure” was released in Paris and Morocco in 1972. When asked why he turned away from Pop Art, Reiser replied: “An artist must avoid falling into rhetoric; doing something else is a way of transcending the problem.”

He would do it again and again during those ten years. Throughout the 1970s, he created a series of knick-knack sculptures called “CocoMato”; revisited psychotherapeutic-style paintings filled with grotesque figures; and began the “Spelunca” series, a series of seven paintings inspired by the Renaissance monk Francesco Colonna The Dream of Polyphilus; and moved to Oussy-sur-Marne in the eastern region of Paris to escape the capital’s art scene. “In order to focus, you have to move away from distractions,” he said of changes in your surroundings.

In 1978, Raysse moved further south to three abandoned houses in the Dordogne region, where he has lived ever since. “At the time, I couldn’t afford to fix the roof,” he said. “For two years, I had a tarp over my head.” A turning point came in 1992, when super-collector and luxury goods magnate François Pinault acquired Périgueux Carnival (1992), a large cast of characters wearing masks and costumes. Subsequently, major exhibitions were held in Paris, Venice, Sète Port and other places, and Raysse’s market value increased significantly. In 2011, when Old age in Capri (1962) sold at a London auction for £4.8 million ($6.4 million), making him the most expensive living French artist. Three years later, the Center Pompidou organized a major retrospective of his work.

martial arts rice, Shire Blue Millet Blue2014.

Photo Laurent Edeline/Courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris – Brussels – New York

Raysse has been meditating for the past 40 years At least 45 minutes a day, starting at 4am. “That’s why I walk on water,” he said with a laugh. But as an artist, he was less strict: “I’m not a union painter!” He took a more serious tone, explaining that his relationship with art was driven by desire. “The artist has an almost physical need to express himself, but there is no fixed time to fall in love.” He was still very prolific, but would only go to the studio if he felt like it.

Raysse seems to have been in a particularly good mood over the past five years. He prefers acrylic, which can be thinned with water and dries quickly, like murals. Paint tubes, glue cans and brushes were of course arranged in order on a large table. “I prefer lean meat to fat,” he says of his choice of ingredients. “I know how to paint in oils, but that’s not part of my story. I’ve always dreamed of painting murals; acrylics remind me of this technique.”

The studio is also home to much of Raysse’s work. Most of the canvases are stacked one on top of the other, while three large works are displayed in their entirety. One depicts a man in a suit stabbing an anthropomorphic creature: george and the dragon (1990), one of Martial Raysse’s earliest mythological paintings. other, Diane Des Terrain Blur (1989), depicts the Roman goddess of the hunt, based on his daughter Alexandra. Both paintings belong to the artist’s personal collection and are not for sale.

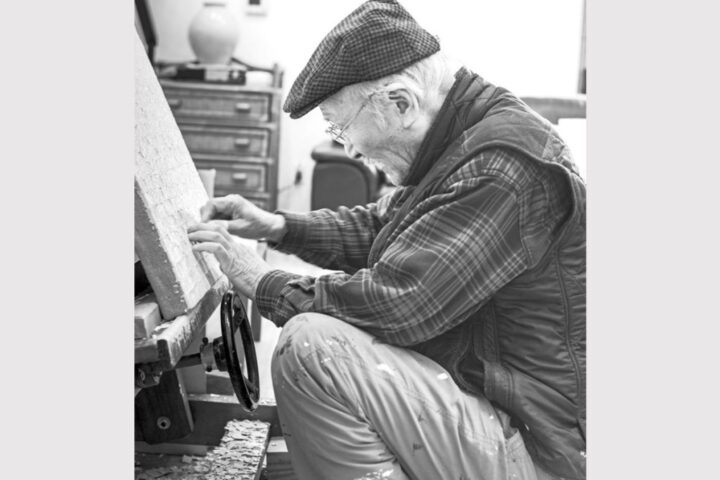

Martial Raysse at work in his studio earlier this year.

Photo by Sarah Belmont for ARTnews.

Against the third wall is an allegorical canvas in progress, referencing a French nursery rhyme. “This is the story of the ferret [who] Grabbing a girl’s scarf and running away, leaving her alone with a piece of fabric, a fragment of their love. The female figure is hidden under a white sheet, while the ferret – or “little rascal” as the artist calls it – is already visible, wearing red shorts and a blue T-shirt. However, the painting did not appear in Raysse’s Templon exhibition because he refused to show the work unfinished. “Many artists exhibit works before they are completed – that’s fraud!” ”

Looking back on the paintings he is working on, Raysse says: “I’m fascinated by candles that are about to go out. At my age, time is heavy. In front of each painting, I wonder if I can finish it.” I ask him if he thinks he has achieved his goal. “I never set any goals, but when I think about it, I’ve done a lot.” He points out that, to be precise, he created more than 2,000 pieces in nearly seven years.