On October 27, 1918, Egon Schiele painted his wife Edith, pregnant and having a fever in bed. She died of flu the next day. He died three days later.

Edith, 25, and Egon Schiele, 28, were two of the 50 million victims who began to sweep Europe in Europe that year. For nearly a decade, Schiele has portrayed his intimate life in art, creating about 3,000 and 400 paintings, and he continues to paint until the end.

Today, Schiele often takes photos of him from the moment he dropped out of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in 1909 and took off from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in about 1914. His mature and sober works are often overlooked.

The museum’s new exhibition “Age of Change: The Last Years of Egon Schiele, 1914-1918”, will open on Friday and last until July 13, trying to change that. The artist’s approximately 130 original works and dozens of personal documents allow you to enjoy Schiele’s later career.

“I wouldn’t say that later work is better than earlier work, and vice versa,” said Jane Kallir. “Their period in Schiele’s life and his creativity is very obvious.”

Kallir called Schiele’s “Expressionist Breakthrough” early works using bright lines and soft colors to present sexy and twisted nudes, usually characters from Demimonde, Vienna.

In 1912, he was arrested, charged with presenting indecent drawings, and staying in prison for 24 days. He also had a notorious relationship with his strawberry blonde model Walberga Neuzil, who was 16 years old when he immortalized her in his famous 1912 oil painting “Portrait of Wally Neuzil.”

Schiele’s wild life broke out in 1914 after World War I. The couple’s first child was born before marriage and lived with their grandmother, giving birth to a second child. Carrier said being an uncle changed the artist’s perception of relationships, parents and women, making him more considerate and serious.

His paintings shift their attention to the emotional life of the babysitter, rather than their posture or sexual behavior. Kallir began to focus, “He is in the mind of humanity. He is indeed grasping the personality of others.”

He also developed his skills as an artist, she added. “In terms of his control over the medium of painting, there is a technical mastery,” said Carrier. “While the painting style becomes more classical, with more volume, more realistic, the painting style is actually more expressionist, and you’ll see bolder dents and brighter colors.”

In 1915, Schiele married Edith Harms, a mean middle-class woman after staying in touch with Neuzil. Edith’s diary is a gift from Schiele before the wedding, revealing intimate details about their most unpleasant lives. The diary is on display on the show and is released for the first time in the catalog.

After a quick honeymoon, Schiele had to join the army. He left Edith at a hotel in Brague with little money and told her to sell food.

Schiele hates military service and writes to many contacts seeking escape. An antique dealer named Karl Grünwald managed to transfer him to a military supply warehouse in Vienna in January 1917, with relatively little responsibility, so he could once again focus on his art.

During the last year of his life, many of Schiele’s creative goals began to crystallize. In March 1918, a sold-out exhibition at the prestigious Vienna Separation confirmed his new figure.

“Schiele was an artist whose mission was to reconcile the contradictions of realism and expressionism, psychological insight and spirituality, and he was always struggling to deal with these elements. He reached a different point of view in merging them in later works.”

“You can see his lines become more organic, calmer, thin, thin,” Jesse said of the artist’s later portraits. “His early works show these very thin characters, but then, his body starts to have life, their hearts beat, and they start to live.”

But with a new sense of vividness in his work, the pandemic that killed him was also taking steps. After World War I, the flu began to spread, and in February 1918, Schiele’s friend and mentor Gustav Klimt died of a stroke, and pneumonia might have been brought by the flu. (Schiele depicts him on the drawings of “The Head of the Dead Gustav Klimt”.) Schiele became the new ruler of Austria and sold everything at his Vienna Schiele.

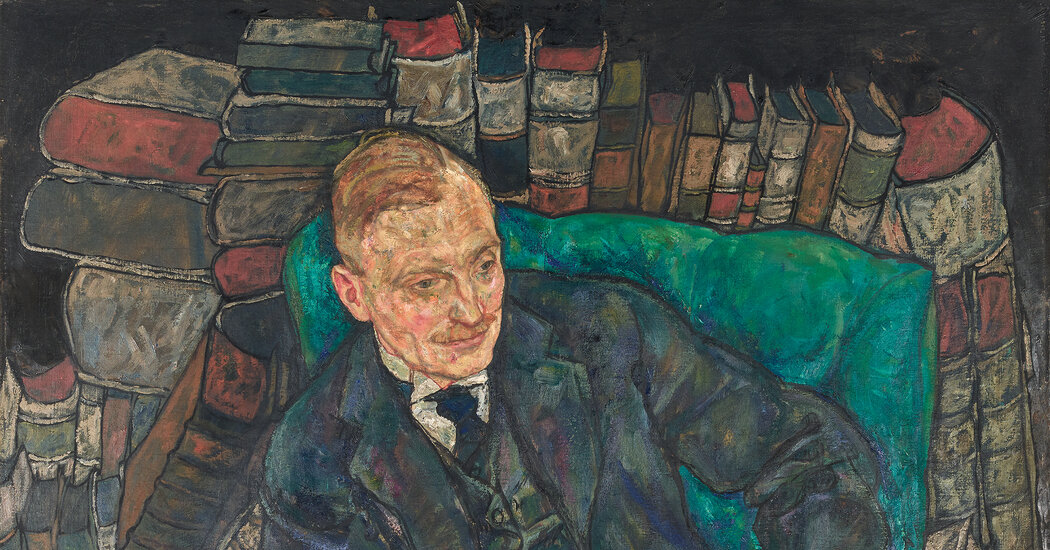

Carlier said his last oil painting was a portrait of his friend painter Albert Parisvon Gütersloh, indicating Schiele was “the pinnacle of his artistic power” when he died on October 31, 1918.

Jesse said that if Skiel had more time, he had already made great contributions to art history, and it was hard to imagine that his contribution to art history had become huge.

“Some artists have done the same amount of work in their careers, which lasted for 50 or 60 years,” she said. “He died suddenly, so we don’t know which way he is going.”

Age of Change: The Last Years of Egon Schiele, 1914-1918

March 28 to July 13, at Leopold Museum in Vienna; leopoldmuseum.org.