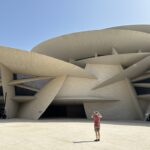

When the first edition of Art Basel opens in Doha, the differences from other fairs will be immediately apparent. This is the smallest Basel fair to date: just 87 galleries, all hosting individual shows and a layout that feels closer to a curated exhibition than a commercial free-for-all. By comparison, Paris has 206 galleries and Miami has 283. While sources tell me that subsequent editions in Qatar will expand to the size of Paris and Miami, the smaller scale of the first edition is intentional. Unlike sister fairs, where aisles can blur into each other and it’s not uncommon to see popular artists on multiple booths, Art Basel Qatar has strict restrictions in place.

Most galleries use only two walls and display only a small number of works. There is no built-in power supply, which effectively rules out video and large installations, and there are no chairs or tables in the booth. (Each gallery, however, offers a custom-designed bench.) Dealers can keep works, but I’m told there are limits on how many, if any, re-hangs are allowed after the fair opens. The result is a show designed to be slower, calmer, and easier to read, especially for those who may not be used to the circus.

During the planning stages, the format aroused concern and even some outrage. Individual booths are nothing new at Baselworld, but requiring them across the board is a shift. It’s not hard to imagine multiple galleries scrambling to argue about who can bring which market darling before signing on the dotted line.

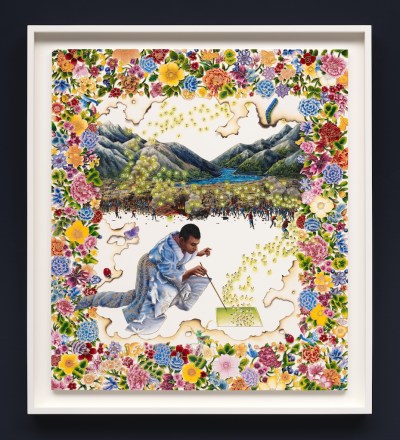

Ali Cherri, The Summoner (Grafting), 2026. © Ali Cherri

Courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech

Art Basel has set the theme of “Becoming” for the exhibition and hired Egyptian artist and Doha Fire Department Chief Wael Shawky as the artistic director of the first art fair. In press materials for the fair, Becoming is described as a loose framework about change and the systems that shape everyday life, with the Bay Area providing a fitting backdrop for this conversation. The specific format is: personal display only, with strict restrictions on booth space and display content.

Unsurprisingly, hosting the expo in the Bay Area also sparked rumors. Some dealers have heard that the Qatar royal family subsidizes freight and booth fees. One gallery told me directly that no such arrangement was offered to them. Others simply avoid the question. Shipping and other costs are subsidized, but the subsidy is provided by Basel, not Qatar, according to a source familiar with the show’s economics who requested anonymity.

Another rumor circulating is that Art Basel will receive huge financial commitments over the next decade in exchange for moving the show to Doha. When asked to confirm whether this was true and the amount committed, an Art Basel representative said, “As a general rule, we do not comment on the financial terms of any partnership.” For comparison, look at the Qatar Web Summit 2026, which takes place in Doha from February 1 to 4. As art market expert Magnus Resch noted in a recent article, the same conference in 2018 signed a ten-year deal worth $128 million with Portugal to keep its capital, Lisbon, the European home of the Web Summit. More than 20 cities competed for the conference. It’s not hard to imagine a similar competition taking place before Art Basel Qatar is established; after all, in 2024, multiple sources told me the fair is partnering with Abu Dhabi. Maybe that city was just one of many trying to get the fair.

What is clear, however, is how differently galleries approach the market.

Almine Rech presents his sculptures and works on paper exclusively to Ali Cherri, exploring history, materials and the body through a grounded, tactile language. According to the gallery, the watercolors in the booth will cost $36,000 and the new sculptures will cost $156,000. Cherri’s work is also on display simultaneously in Almine Rech’s Tribeca space, providing multiple entry points for collectors.

At VeneKlasen, new paintings by British artist Issy Wood are on display, priced between $35,000 and $190,000. The booth also has additional significance: it is the first fair organized by Gordon VeneKlasen under the name VeneKlasen (he recently parted ways with Michael Werner), and his gallery will officially open on February 1st.

Raqib Shaw, Revelation 1: To all countries without post offices (2025)

The focus of Thaddaeus Ropac is Raqib Shaw, whose colorful and confident works on paper sell for about $254,000 and paintings for about $900,000. The pricing places the presentation at the higher end of the show, at a time when galleries are taking a variety of approaches to aggressively price work in Doha.

This disagreement over strategy came up repeatedly in reporting this story. Some galleries said Doha was wise to bring in top-notch work at high prices, signaling that this was a fair worth taking seriously from day one. Others take the opposite view: appeasing collectors with lower prices and a clearer entry point is the only way to build confidence in a market that is still forming. Walking on the floor, you can see both ideas at work simultaneously.

Elsewhere, the solo format makes familiar names more compelling. Hauser & Wirth presents three major paintings by Philip Guston, including dialogue (1978), a late self-portrait painted towards the end of his life. last time dialogue In 2007, the work went on the market and brought in $2.7 million at Christie’s fall evening auction. Order, Also from 1978, the work had appeared at auction as early as 1989, when it sold at Sotheby’s for $528,000.

Philip Guston, dialogue (1978) Housewell and Voss

David Zwirner also presents three paintings by Marlene Dumas, all from the artist’s “Up the Wall” series, which was first exhibited at the gallery in 2010. Works from the series are in the collections of very important institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Broad Museum and the Dallas Museum of Art, the gallery said. Most of these works were drawn from media images and clippings related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict provided by Dumas.

Meanwhile, White Cube showed Georg Baselitz, Mignoni showed Donald Judd, Gladstone Gallery showed Alex Katz, and Acquavella Gallery showed Jean-Michel Basquiat. These are artists familiar to Basel regulars, but the minimalist setting makes their work feel less like inventory and more like a stance, and signals the dealer’s desire to attract institutional attention.

All in all, Art Basel Qatar feels less like an offshoot and more like a test case. Could the show be a little quieter without losing a sense of urgency? Can fewer works carry more weight? Potential collectors in the area (that’s what this fair is for, don’t be fooled) will respond to clarity rather than overload. By the end of Tuesday’s VIP preview, dealers will have a better idea of which strategy paid off. Regardless, the inaugural Art Basel in Doha is already doing something unusual: forcing the art world to slow down simply because there is less to absorb.