February 19, 2026

Seoul – South Korea’s Seoul Central District Court will rule on Thursday on whether former President Yun Seok-yeol led the rebellion by declaring martial law on December 3, 2024. The ruling will define the legal implications of the crisis and the scale of penalties that will follow.

The court’s Criminal Division will rule at 3pm on Thursday, 443 days after Yoon Eun-hye’s late-night decree triggered South Korea’s worst constitutional unrest in decades. The hearing will be broadcast live.

On Wednesday, Yoon’s legal team said he would attend the sentencing, refuting speculation that he would be absent after several previous court hearings. His lawyer added that there were no plans to provide further written submissions.

Special prosecutors pointed out that Yoon was a rebel leader under Article 87 of the Criminal Code and sought the death penalty.

Under the statute, rebel leaders face the death penalty or life imprisonment. Article 87 defines rebellion as an uprising within South Korean territory aimed at excluding state power or disrupting the constitutional order.

If the court finds that Yin led the rebellion, the sentencing range will actually be narrowed to these two penalties, and severe punishment is inevitable.

According to the indictment, Yin conspired with senior security officials to declare martial law in the absence of war or an equivalent national emergency.

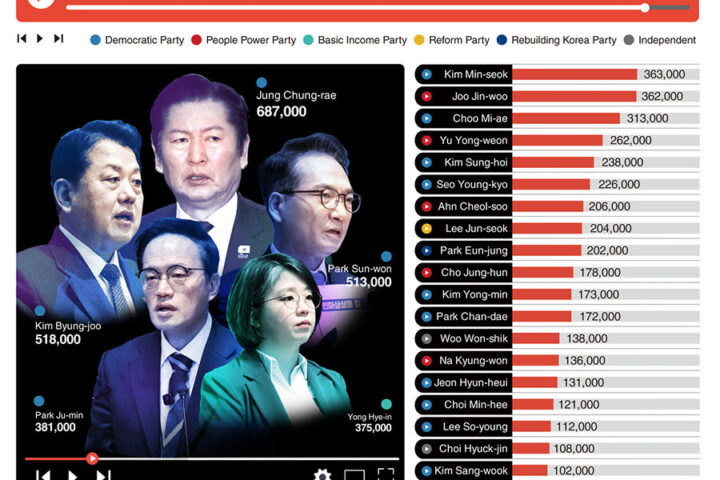

Seven senior military and police officials who are co-defendants, including former Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun and former National Police Agency Chief Cho Ji-ho, will also be sentenced for their participation in rebellion.

Shortly after Yin declared martial law, armed forces and police were deployed to blockade the National Assembly.

Soldiers smashed windows and entered the building as police blocked access. But lawmakers forced their way in and passed a resolution shortly after midnight calling for the lifting of martial law. Yin removed the decree at 4:27 a.m.

Prosecutors argued the move was aimed at silencing the legislature and undermining a core pillar of constitutional democracy. They claimed they planned to detain key politicians and election officials, framing the incident as an attempt to subvert the constitutional order.

Yin denies this characterization.

In his final court statement, he said the decree was a legitimate exercise of presidential power and a warning to the public about what he said was legislative overreach by the opposition. “This is a call for people to pay attention to politics and defend the country,” he told the court.

He made no apology for the riots that ensued and argued that the rapid withdrawal of troops after the parliamentary vote was proof that parliament had no intention of imposing military rule.

The case also tested the authority of the Senior Officials Corruption Investigation Office.

Yin’s legal team argued that the agency lacked jurisdiction to investigate the insurrection and that alleged procedural flaws, including the division of detention periods between agencies, rendered the prosecution ineffective.

The investigation was marked by an unusual turf war between prosecutors, police and the chief information officer, raising questions about overlapping investigations before the cases were consolidated.

However, in a separate ruling last month, another panel of the same court recognized the agency’s authority to investigate abuses of power and said the underlying facts were directly related to the insurrection charges.

Yoon became the first sitting South Korean president to be arrested after investigators made a second attempt to execute an arrest warrant. Initial efforts were thwarted when presidential security officials set up a human wall to block entry.

He was formally detained in January 2025 and formally removed from office by the Constitutional Court in April, when the court confirmed Yin’s impeachment.

Lower courts have taken firm stances in related cases. Former Prime Minister Han Deok-soo was sentenced to 23 years in prison, more than prosecutors had requested, in an incident that a judge described as a top-down rebellion or self-coup.

The determination that the December 3, 2024 statement constituted an insurrection is a prerequisite for assessing whether Han Kuo-yu participated, rather than a direct determination of whether Yoon himself led the operation.

Former Interior Minister Lee Sang-min was sanctioned seven years after a court found him aiding the effort, but played a more limited role, again using the results of the insurgency investigation as the basis for assessing involvement.