By some measures, democracy is in downward decline in quite a few countries across the world, while censorship is only increasing. (A coincidence? Hardly.) But even with so much valid concern about the fragility of the world order more broadly, artists pressed ahead in 2025, producing valuable works that contended with police violence, abuses of power, fallen monuments, climate change, and trans rights.

This list taking stock of the 25 artworks that defined the year includes many pieces confronting these issues. Not every work here is a protest, of course; there are also pieces that conjure science-fictional worlds and new possibilities for abstraction. (Not every artwork is even particularly great—we’ve included one piece we really didn’t like but found significant nonetheless.) But in a time when freedom of expression is under threat, just about any kind of art feels political in its own way. This list is a reminder that artists can, and will, forge onward, even in the darkest moments.

It’s also a reminder that artists did just that in the past, too. To complement the new and recent artworks featured here, we’ve also roped in some older pieces that speak well to our current mood. These works show that history is unsettled—particularly at a time when some political forces would prefer for the past to remain set in stone. —Alex Greenberger

Adrien Brody, My Marilyn

Image Credit: Photo Alex Greenberger/ARTnews We loved Adrien Brody in The Pianist (2002) and The Brutalist (2024), but “the artist” is a role he is unable to master, judging by the ridiculously bad, overdetermined products on view in his summer show “Made in America,” in which he portrayed iconic characters like Mickey Mouse and Marilyn Monroe, who artists great (Warhol) and not-so-great (KAWS, Banksy) have long since worked with. But the show was seemingly all anyone could talk about. In another great movie, The Matrix (1999), when Joe Pantoliano’s character is going to be plugged back into the fake world, he says, “I want to be rich. Someone important. Like an actor.” But even some actors, with all their money and fame, deep down, just want to be artists. Is that at least something that artists can feel good about? —Brian Boucher

Lu Yang, DOKU the Creator, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy Amant As hysteria over AI reached a fever pitch this year, artists began tackling the technology’s implications in refreshingly off-kilter ways. Shanghai-born, Tokyo-based artist Lu Yang is a case in point. Though the artist has been creating videos, installations, and interactive works featuring his virtual avatar Doku since 2020, this year Yang debuted a new installation, DOKU the Creator, that became the talk of Art Basel Hong Kong. (It later traveled in a modified form to the Amant art space in Brooklyn.) The piece is a sensory overload of an installation anchored by an hour-long video in which Doku moves through a surreal dreamscape that blends video game animation with AI-generated imagery.

In Hong Kong, the video was presented inside an interactive installation that included a pop-up store. Works were sold in “blind boxes,” each hiding one of 108 possible pieces—a setup that laid bare the casino-like nature of the art market. The video and its surrounding environment evoke an art world in which the artist is no longer essential to the system’s functioning. Doku appears to operate autonomously, free to create, destroy, and mourn the value of art without any mediation by its creator. What distinguishes Yang’s work from other AI critiques is that he seems unbothered by this state of affairs. Drawing on Buddhist philosophy, he suggests that all creation functions like an algorithm—endlessly combining and recombining the totality of human thought and creativity into conceptual forms. Our mistake, he implies, is in attaching too much meaning to the artist, or their originality, at all. In the end, they are all temporary illusions. —Harrison Jacobs

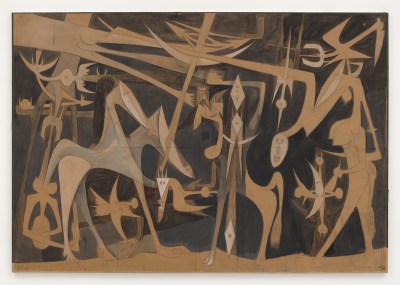

Wifredo Lam, Grande Composition (Large Composition), 1949

Image Credit: ©Wifredo Lam Estate/Adagp, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Museum of Modern Art Surrealism—which just celebrated its 100th anniversary—is having a moment even as its canon grows ever more inclusive, with rising auction prices for Surrealist works by women, a run of expansive institutional shows like 2022’s “Surrealism Beyond Borders,” and growing interest in formerly underknown figures such as Les Lalanne. A case in point is the Museum of Modern Art’s current Wifredo Lam retrospective, on view through April 11, which presents the Cuban Surrealist painter as a transformative figure rather than an exotic offshoot of a primarily European movement. Of Chinese and African descent, Lam was deliberate about using Afro-Caribbean imagery in his works, famously telling art historian Gerardo Mosquera that his art was “an act of decolonization.” A highlight of MoMA’s exhibition is Lam’s painting Grande Composition (1949), which features a hybrid horse-human taken from the African diasporic religion Santería. The work epitomizes Lam’s belief in what he told Mosquera was “the importance of bringing the Black presence into art.”—Anne Doran

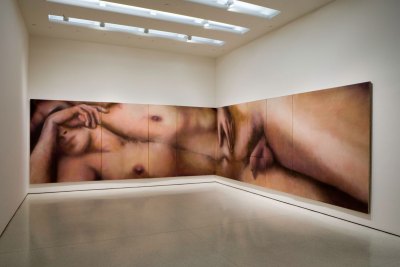

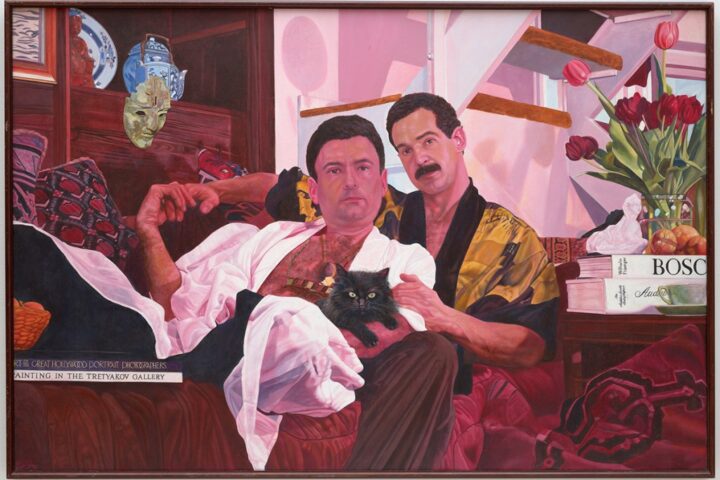

Harold Stevenson, The New Adam, 1962

Image Credit: Art: ©Harold Stevenson/Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Photo: ©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, All Rights Reserved Invited to create a work for the Guggenheim’s 1963 Pop Art exhibition “Six Painters and the Object,” artist Harold Stevenson produced The New Adam, a 40-foot-long wraparound painting of a nude man. (Actor Sal Mineo was the model for the body; the partially obscured face is that of Stevenson’s lover at the time, British aristocrat Timothy Willoughby.) It was rejected by the show’s curator Lawrence Alloway, who wrote, “[The] problem . . . is publicity, rumor, and all those entertaining things which would go along with exhibiting a nude with a phallus the size of a man.” More than 60 years later the time finally seems right for Stevenson’s gargantuan canvas, which not only celebrates the male body but expresses homosexual desire at a scale impossible to ignore. It is currently on view through January 19 in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition “Sixties Surreal.” —Anne Doran

Claudia Alarcón & Silät, Un coro de yicas, 2025

Image Credit: Photo Izzy Leung Few works in 2025 carried the cultural and political weight of Un coro de yicas (A chorus of yicas), the centerpiece of Claudia Alarcón and Silät’s exhibition at James Cohan. The installation—composed of 100 hand-woven yica bags—made visible a lineage of Wichí women whose textile knowledge has been passed down by generations and until recently dismissed as craft. Each yica is made using chaguar fibers harvested, processed, spun, dyed, and woven through a communal, intergenerational labor system that Alarcón learned at age 12. The work crystallizes what their practice represents: not formalist abstraction but a living language, a structure of communication, memory, and autonomy passed from mothers to daughters across the Alto la Sierra and La Puntana communities in Argentina. Seen together, the 100 bags operate as both archive and chorus, a collective declaration of presence at a moment when Indigenous women’s labor is finally being recognized as contemporary art. —Daniel Cassady

Ser Serpas, tube of brief cadavers made sadder still, 2025

Image Credit: Kris Graves/Courtesy MoMA PS1 This mixed-media sculpture by Ser Serpas featured in the MoMA PS1 exhibition “The Gatherers,” which brought together the work of artists whose practices collect and accumulate various forms of detritus in a world that is increasingly wasteful and on the brink of environmental collapse. Serpas is one such young artist who has injected new energy into this form of assemblage. Her installation, titled tube of brief cadavers made sadder still, might on its surface resemble a trash heap at a dump, but the two main items juxtaposed together—a plastic orange saddle-like contraption that could be part of a boat, and shredded silver fabric recalling emergency blankets—lend the piece a connotation of migrants fleeing by sea. Its haunting title seems to confirm that allusion, memorializing those who do not make the crossing and, more recently, those who are being targeted in such boats. —Maximilíano Durón

Bruce Yonemoto, Broken Fences, 2025

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews The history of Japanese internment—when the United States government detained and imprisoned its own citizens—never seems to loom as large within American consciousness as it should. Perhaps that might change with Bruce Yonemoto’s Broken Fences, which debuted in the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial this year, where it emerged as one of the show’s standouts. For the piece, Yonemoto has constructed two fence-like armatures into which he has embedded video screens. On the screens play two sets of propaganda—sometimes side by side, sometimes separately: one produced by the U.S. War Relocation Authority documenting the deportation of Japanese Americans, and one created by the Nazis about the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Both falsely promote the supposed “benefits” of these detentions. (The work’s dominating audio, however, comes from the German propaganda film.) Yonemoto poignantly underscores how two opposing wartime powers deployed strikingly similar visual and rhetorical tools, drawing a chilling parallel between their methods and the ideologies they served.—Maximilíano Durón

Ayoung Kim, Delivery Dancer’s Arc: Inverse, 2024

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and ACC More so than any other artist this year, South Korean phenom Ayoung Kim took the American art press by storm, with her work appearing on the cover of simultaneous issues of Artforum and Frieze this fall. (ARTnews also profiled her around that time, too.) There’s good reason to be suspicious of any artist who receives so much attention so suddenly, but Kim is the real deal, as proven by her current MoMA PS1 exhibition and a Performa commission staged this past November. The centerpiece of her PS1 show is this video installation, one of three chapters in a trilogy of works about motorcycle-riding female delivery workers who seem to attract and antagonize each other. Projected onto three formidably sized screens that hang from the ceiling, Kim’s footage switches seamlessly between imagery made using gaming engines and AI, and often displays impossibly tall ramps and staircases in futuristic worlds. Those worlds may not look ours, but the workers who scale them are navigating a capitalistic rat race that feels a lot like the one of the present. —Alex Greenberger

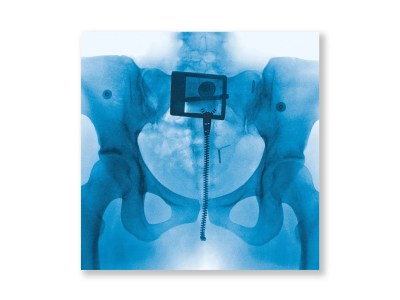

Heji Shin, cover for Lorde’s Virgin, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy Republic Records The mercurial pop-music star Lorde tapped the art world in a number of ways in the promotional push around her fourth studio album Virgin, including a video that alluded to Walter De Maria’s seminal Land art work The New York Earth Room and, in a booklet that accompanied the vinyl LP, a bare-it-all picture of a waist in see-through pants by photographer Talia Chetrit. But the cover of the album was the master stroke: an X-ray image of a pelvis by Heji Shin. Bones in the arresting image are joined by a zipper (the same one as in the pants in Chetrit’s photo?) and an IUD. —Andy Battaglia

Goldin+Senneby, “After Landscape,” 2024–

Image Credit: Photo Dario Lasagni This one’s very meta. When climate protestors threw soup on Van Gogh’s sunflowers and mashed potatoes on Monet’s haystacks, their detractors decried defacing any art. Never mind that all their targets were protected with plexiglas, a veneer made from fossil fuels poetically shielding these human-produced views of nature, which apparently seemed more precious to some than nature itself. Beyond the ragebait headlines, the boring moralist should-they-or-shouldn’t-theys, the protestors’ gesture blurred protest and art in more ways than one. A series by Goldin+Senneby honors the Just Stop Oil group’s conceptual heft while turning cries of conservation on their head. Working with professional conservators, the duo meticulously recreated each splattered plexi vitrine to scale, showing them against blank walls and turning them into paintings themselves. You can bask in their irreverent glory at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, where I first saw them, through mid-March. —Emily Watlington

Wafaa Bilal, Domestic Tension, 2007

This is a game: Move your mouse across a digital landscape, select your drone’s target, press “X” for death. In Domestic Tension, Iraqi American artist Wafaa Bilal argues that this is the numbing ease of modern warfare—where the distance between people and their would-be killers has been so thoroughly abstracted that devastation can be delivered from an office chair. The piece stands as an example of what Bilal has called a “networked performance.” He confined himself to a Chicago gallery for its duration, broadcasting live online 24/7 and inviting viewers to chat, observe, or—if they were so mysteriously compelled—shoot him with a robotically-controlled paintball gun. (Non-lethal bullets still hurt.) Domestic Tension simulated the unending anxiety faced by Iraqis worldwide, forced to anticipate violence—whether physical, like a US-made bomb, or existential, as the so-called War on Terror legitimized racism: it’s acceptable to fire, so long as the target is Arab. —Tessa Solomon

P. Staff, Penetration, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist On most days, David Zwirner’s townhouse on New York’s Upper East Side functions well as a domestic space converted into white-cube gallery, but during the run of P. Staff’s remarkable show there this fall, the building’s spiral staircase was occasionally drenched in a haunting shades of blue. The source of that emanation was Penetration, a video projected across all three of the gallery’s floors, in which a figure stands stoically in a darkened space. A laser beam shoots through the void, aimed directly at this person’s stomach. What did that mean? Never one to let viewers off the hook easily, Staff did not offer many clues, though those familiar with the artist’s past work might recognize in this video a statement on the surveillance of bodies that do not conform to conservative gender norms. That kind of violence is endemic right now in the US—the Trump administration recently announced a measure that would keep trans Americans from changing their gender on their passports—but Staff notably did not explicitly portray it. Sometimes, everyday life is scary enough. —Alex Greenberger

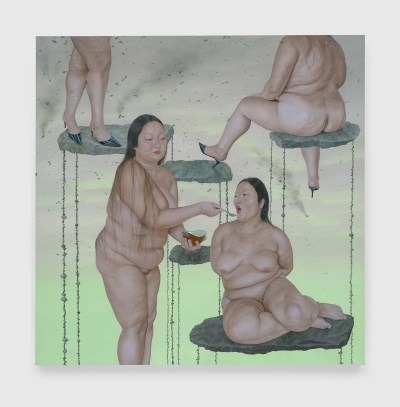

Sasha Gordon, Husbandry Heaven, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy David Zwirner The trend of women painting women and calling it “feminist” has been brewing for some time, but it exploded this autumn in what I dubbed “feminist figuration fall.” Yet there is a clear divide between work trafficking in—and profiting from—pastiche and normative fantasy, and those building new, feminist worlds. Amid it all, Gordon’s show at David Zwirner stood out. In this particular painting, luminous skin glows eerily green and is punctuated with cellulite and stretch marks. Meanwhile, each of our subject’s long hairs are rendered individually. Gordon stands naked in this self-portrait save for a pair of black kitten heels, not just echoing Manet’s Olympia but talking back to it. The work both repels and allures at the same time, drawing you in, then challenging all your first impressions. She’s not relying on normative ideas of beauty as a crutch so much as reimagining what beauty might be. —Emily Watlington

Laura Owens, “Laura Owens,” 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy Matthew Marks The difficulty of trying to remember all the little details in Laura Owens’s brain-bending painting/installation/show at Matthew Marks Gallery rhymes with the way that those details were hard to discern even when in their presence, in real time. The artist’s brush had bristled and stroked different dimensions, making for trompe l’oeil effects that twisted into spirals while turning inside-out and back again. Here too were traces of “painting” (as well as sly admonitions of it), as evident on the walls as they were on canvases that almost seemed to play a supporting role. Moving through the hidden door connecting the show’s two main spaces—each adorned with paintings of wallpaper and inexplicable things like pretzels floating in the air, and one with tiny mechanical panels that opened to reveal still more painting inside—gave rise to the most thrilling idea of an “art gallery” rather than the too-often humdrum reality of one. —Andy Battaglia

Alex Reynolds and Robert M. Ochshorn, A Bunch of Questions with No Answers, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy the artists This piece is a monumental act of witnessing: a 23-hour video drawn entirely from footage of U.S. State Department press briefings spanning October 2023 to January 2025, the end of the Biden administration. What begins with a journalist politely stating “I have a couple of questions” becomes an epic portrait of governmental irresponsibility as reporters—bleary, persistent, increasingly furious—try and fail to obtain clarity on Israel, Palestine, and the United States’s role therein. By editing out the spokesmen’s evasive, nothingburger replies, with cuts at times turning officials’ remarks into syllable salads, Reynolds and Ochshorn leave only the questions, revealing the briefings as a looping theater of deflection. It’s a horror film without the jump cuts: we watch the State Department rebrand its atrocities through the art of PR, confident in its own immunity.

Presented without commentary, the footage indicts by showing instead of telling: this system will neither acknowledge its hypocrisies nor confront the human cost of its policies. As the genocide escalates and trust erodes, the journalists’ inquiries move from specific facts toward procedural and ethical pleas—“How do you know?” “Is there any plan?”—questions that echo far beyond the room. The film stands as one of the year’s most urgent artworks, a stark record of accountability sought and systematically denied. —Emily Watlington

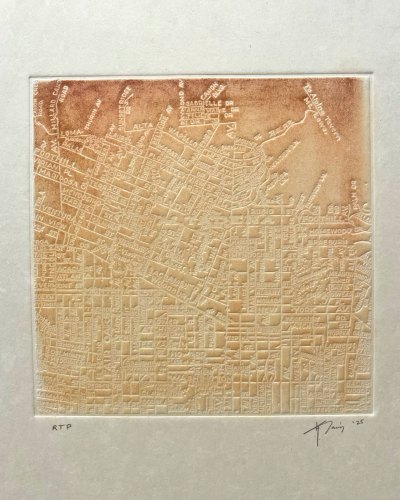

Kenturah Davis, Altadena, 2025

Image Credit: Maximilíano Durón/ARTnews The beginning of the year saw Los Angeles hit by devastating wildfires, including the Eaton Fire, which decimated parts of Altadena, an unincorporated part of Los Angeles County that for generations has been home to a thriving home of Black creativity. In response, Kenturah Davis created an embossed editioned print that featured a vintage map of Altadena onto which she had rubbed pigment that incorporated soil from outside her home, which burned in the fires. Altadena featured in an exhibition mounted by the California African American Museum just months after the wildfires to reflect on the immense loss and featured three generations of the Davis family. A work like Davis’s is a testament to the community’s resilience: from the ashes, a new Altadena will rise. —Maximilíano Durón

Omar Mismar, Still My Eyes Water, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy Taipei Biennale How does one represent Palestine? It’s a question that has plagued artists and writers throughout the last century, as even the most seemingly anondyne depictions can’t help but become freighted with meaning and political valence—a tendency that has only grown since October 7 and Israel’s war in Gaza.

In a work commissioned for the Taipei Biennial, Omar Mismar lands on a towering sculpture of flowers. The work is suffused with an unending grief, with the flowers evoking the ones placed typically at a tombstone. But Mismar is after something more complicated: the flowers are artificial, made out of fabric and modeled after illustrations found in Flowers of Palestine (1870), a book by Swiss missionary Hanna Zeller. Here, Mismar tackles a contradiction inherent in the idea of Palestine: some of the most detailed preservations of the land and culture were those created from a colonial gaze. The flowers do not wilt or smell. They are forever perfect, if inert. But read another way, Palestine remains an idea that will not wilt or die, due in no small part to the grief it inspires. —Harrison Jacobs

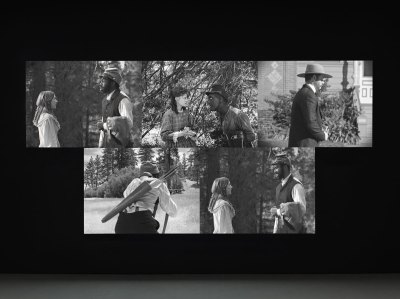

Stan Douglas, Birth of a Nation, 2025

Image Credit: Photo Olympia Shannon More often than not—and often for the worse—US history is a work of fiction at the mercy of its makers. This provocation animates Stan Douglas’s five-channel film installation, Birth of a Nation (2025), which reframes one of cinema’s most insidious legacies of white supremacy: the 110-year-old Klan rallying cry that shares its name. For it, Douglas, a keen reader of the messages smuggled into our media, constructed an alternative narrative to a pivotal 13-minute section of D. W. Griffith’s original film, in which a Black soldier named Gus pursues a young white woman to the edge of a cliff. Though this is a tragic case of misidentification, the woman ultimately leaps to her death to escape his designs, a moment intended by the film to obliterate any sympathies that still stood for formerly enslaved Black Americans at the height of Jim Crow; the soldier—played by a white actor in blackface—is later lynched. While this scene loops on one screen, the other four present alternate outcomes of the same sequence of events made possible by new perspectives included in Douglas’s script. The characters are released from their crude casts of “villain,” “damsel,” and “hero,” and open the possibility that viewers, too, might question how they’ve looked away from a clearer, more complex picture of the powers shaping our prejudices. —Tessa Solomon

Thomas J. Price, Grounded in the Stars, 2023

Image Credit: Photo Liao Pan/China News Service via Getty Images Sometimes, an artwork gains new importance for reasons that are less than fortunate, and that was the case when Thomas J. Price’s Grounded in the Stars visited Times Square over the summer. The piece had already appeared elsewhere, generating little controversy in the process, but when Grounded in the Stars came to New York, the sculpture suddenly gained the attention of conservative reactionaries, who mocked Price’s piece online, remaking it in racist memes and as AI slop. What, exactly, was so offensive about a 12-foot-tall statue of a Black woman standing around? Most of the sculpture’s detractors seemed to deflect the question in social media tirades and op-eds, though it was clear that a larger debate about monuments—who deserves to be represented with them, and who they are for—hung in the background. With Trump now calling for the reinstatement of monuments that were “removed or changed to perpetuate a false reconstruction of American history” in 2020 or afterward, pieces like Grounded in the Stars suddenly seem even more essential. —Alex Greenberger

Nadya Tolokonnikova, Police State, 2025

Image Credit: Photo Zak Kelley. Courtesy LA MOCA. More than a decade after Pussy Riot cofounder Nadya Tolokonnikova was incarcerated in Russia, the artist returned to a prison of her own making in her performance installation Police State (2025) at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles this June. Tolokonnikova reimagined her prison cell as a space for art—a form of reclamation not only for herself but also for the Russian, Belarusian, and American prisoners whose pieces were incorporated into the installation. Inside, visitors could observe Tolokonnikova making music or art, or even resting throughout the day, via security camera footage and peepholes. The eerie authoritarian state came to life extended beyond MOCA, however, when anti-ICE protests erupted and the National Guard was deployed. With Police State unexpectedly closed to the public during the protests, Tolokonnikova continued staging the work in private, underscoring the piece’s continued relevance amid the ongoing political conflicts in the US and abroad. —Francesca Aton

Cameron Rowland, Replacement, 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist You can basically count on art by being censored for obscenity and support of matters like the Palestinian cause. But how can a simple flag cause trouble? That’s at the heart of the mystery behind Replacement by Cameron Rowland. Shown at the Palais de Tokyo as part of the show “Echo Delay Reverb,” the piece consisted simply of the flag of Martinique, an overseas department of France, flown above the Paris institution where a French flag is typically hung. Martinicans have fought for freedom from French rule for centuries, the artist pointed out in an accompanying text, and the flag replaced the customary French one. Within a day, the Palais de Tokyo removed the work, posting a text noting that the piece may be “considered illegal.” How? No one has elaborated. Score one for the power of the most minimal artistic gestures to cause a ruckus. —Brian Boucher

Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo (Puppies Puppies), Liberté Morte (Dead Liberty), 2025

Image Credit: Courtesy the artist and Balice Hertling In 2016, Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo staged a performance called Liberté, in which performers of various gender identities dressed as the Statue of Liberty, turning a common New York tourist attraction into a kind of drag show. Nine years and two Trump administrations later, Kuriki-Olivo created a sequel in the form of Liberté Morte (Dead Liberty), a sculpture in which a Statue of Liberty costume is splayed out on a plinth. It was a a darker, more sinister approach that responded to the increased marginalization of trans people in the US between Trump administrations, and it suggested that freedom—a fragile notion right now—may be as good as dead in America. —Francesca Aton

Amy Sherald, Trans Forming Liberty, 2024

Image Credit: Kevin Bulluck/©Amy Sherald/Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Trans Forming Liberty (2024), a painting depicting the Black trans-femme model and performance artist Arewà Basit carrying a torch à la the Statue of Liberty, made its debut last year at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in Amy Sherald’s survey “American Sublime.” It didn’t cause controversy there or at the Whitney Museum, where the exhibition went next. But before the show traveled to the Smithsonian-run National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., the museum reportedly tried to remove the painting, leading Sherald to cancel the exhibition and allege censorship. Instead of shying away, Sherald told the New Yorker that the work “demands a fuller vision of freedom, one that includes the dignity of all bodies, all identities. Liberty isn’t fixed. She transforms, and so must we.” The painting thus became a symbol of protest—and even served as the cover for the August 11 issue of the New Yorker. —Francesca Aton

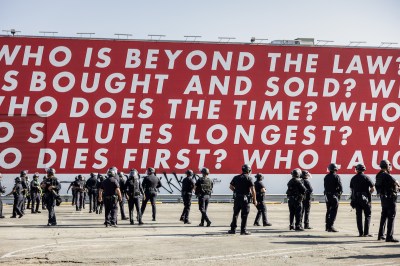

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Questions), 1990/2018

Image Credit: Photo Jay L Clendenin/Getty Images The notion that history repeats itself is both a cliché and a truth, and it is one that Barbara Kruger has always considered in her work, which often finds her remaking the same textual statements about power using the same signature font, just in different settings. Featuring such phrases as “WHO IS BEYOND THE LAW?,” Untitled (Questions) ended up proving Kruger’s point when it figured so prominently in the background of the anti-ICE protests that roiled Los Angeles over the summer. Pictures of the National Guard standing beneath Kruger’s mural, sited at the Geffen Contemporary venue of the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, seemed to answer the artist’s questions well enough, so it was hardly a shock when the photographs went viral. What was more surprising was just how closely those pictures mirrored ones taken in the same place in 1992, when the National Guard was deployed to LA to quell demonstrations following Rodney King’s beating by members of the Los Angeles Police Department.

In 2018, Kruger said of Untitled (Questions), “It’s both tragic and disappointing that this work, 30 years later, might still have some resonance.” Seven years on, it remains both tragic and disappointing that Kruger is always right. —Alex Greenberger

Kara Walker, Unmanned Drone, 2023

Image Credit: Fredrik Nilsen/Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and The Brick. There’s something familiar yet uncanny about Kara Walker’s Unmanned Drone, which this year served as the focal point of The Brick’s portion of the “Monuments” exhibition. For this towering sculpture, Walker dissected and dismembered a decommissioned statue of Stonewall Jackson atop his horse, Little Sorrel, that once stood outside a courthouse in Charlottesville, Virginia. The original, unveiled in 1921 and made by Charles Keck, stood 13 feet high and 16 feet long. Walker’s version is just as monumental but deliberately fragmented, deconstructing the myth built around Jackson in the decades following the Civil War to prop up the falsehoods of the Lost Cause—namely, that had Jackson not met an untimely death, the Confederacy would have won. By taking apart the statue and soldering it back together so that Jackson’s and Sorrel’s body parts merge in confounding, often grotesque ways, Walker lays bare the mechanics of myth-making. She shows how the building blocks of racist historical narratives can appear too large to dismantle but, in fact, can be slowly unraveled to expose the lies beneath.—Maximilíano Durón