The first edition of Art Basel Qatar will not be held in a conference center or an enclosed playground. Instead, it is embedded directly into the newly built Msheireb Doha city centre. The show spans two venues – the M7 Building and the Doha Design District – about two blocks apart, close enough that walking between the two venues doesn’t feel like a chore.

The M7 is designed as a work center rather than a neutral exhibition enclosure. It aims to support designers from concept to market, with an infrastructure designed to encourage collaboration, production and sustainability in fashion and design. The Doha Design District is just a short walk away, creating a contrasting atmosphere. In just two years, it has positioned itself as a local home for global design brands and architecture studios, hosting immersive presentations of major brands such as Dior and Fendi as well as emerging Qatari brands and restaurants. Together, the two venues create a split-screen vision of Doha’s cultural ambitions: one oriented towards production and long-term infrastructure, the other towards visibility and global fluency.

The walk between them is where Art Basel’s presence is most evident. The streets were lined with dark auburn banners – the same color used on Qatar Airways’ uniforms and national advertising – creating a visual corridor between the venues. At times, the route resembles a soft-focus red carpet. Literally, you will be guided from one space to another.

Art Basel Qatar may be small but well-structured. Other shows should be jealous. All galleries host individual showings and have strict restrictions on booth construction, with an emphasis on clear legibility. The best booths here don’t compete for attention, but stand out because the artists have amazing visions.

If there’s one thing Qatar seems to understand – beyond the scale of its investment – it’s brand building. In Doha, Art Basel is presented as part of a larger visual and institutional choreography that extends from gallery walls to streets, buildings and the city’s self-image.

Torkwase Dyson from Grey

Photo credit: Photo courtesy of Gray Chicago/New York. © Tokwas Dyson

Gray Gallery in New York organized a display around one work: niya (2026), a monumental sculpture made of steel, graphite, paint and wood by Torkwase Dyson. The scale is huge. The work consists of two identical notched semicircles, extending horizontally and vertically, with sweeping arcs broken by sharp structural openings.

The sculpture, part of Dyson’s “Memory Horizons” series, behaves more like an environment than an object. You should move along it, noting how the curved planes open up into tighter vertical spaces. Materials are important. The graphite coating darkens the surface enough to absorb light rather than reflect it, keeping the piece grounded even in its largest moments.

Dyson once described niya— a word that translates to “purpose” in Swahili — as a meditation on thresholds. This idea requires no explanation. In Doha, where the fair itself is testing what it means to build an art market before it even exists at all, the work’s emphasis on movement, passage and space feels appropriate.

Katsumi Nakai, Luxembourg company

Image source: Luxembourg company

The Luxembourg-based company is showing a series of sculptural paintings by Japanese artist Katsumi Nakai, whose work revolves around an unlikely obsession: hinges. Born in Hirakata, Japan, in 1927, Nakai came of age during World War II and began traveling extensively, eventually settling in Milan in 1964, where he spent the most productive decades of his career.

What you see in the booth are wooden panels that have been cut, assembled and reassembled using hinges, allowing the pieces to open, fold and move in real space. These are not paintings that stand still. They express themselves through movement, even when static. The panels tilt forward or back, creating shadows and distractions that change as you walk across them.

Nakai developed this approach after moving away from expressive abstraction in the mid-1960s toward language built around literal openness. Hinge became his way of thinking through structure, possibility and transformation. In Milan he was associated with artists associated with the Naviglio Gallery, including Enrico Castellani and Lucio Fontana, but his work was never fully identified with any single movement. The effect is both playful and rigorous.

Fergus McCaffrey

Image credit: Photography by Nicholas Knight, courtesy of Fergus McCaffrey.

Fergus McCaffrey’s booth is centered around Shigeko Kubota’s booth Duchampiana: Video Chess (1968-1975), a video sculpture derived from Kubota’s documentation reuniona 1968 performance featuring Marcel Duchamp and John Cage playing chess on an electronic chessboard designed by Lowell Cross.

The work is simple enough to describe, but strange to experience. A video monitor is located underneath a clear glass chessboard with the chess pieces clearly visible. On screen, Kubota’s manipulated photographic slideshows (taken from her documentation of events) loop through images of Duchamp and Cage, accompanied by an original live score composed by Cage. As the chess game progresses during the performance, each move triggers a different combination of sounds in speakers distributed around the audience.

Kubota spent several years reworking this material, colorizing and animating the photographs and ultimately turning the document into a sculptural system. In a fair context, this piece stands out because of its tactility. This is video art as seen with your own eyes. You look down at it. You’ll hear it before you fully see it. In a show with almost no screens, “Video Chess” feels less like a artifact of the medium’s history than a reminder that video can still have its place. Add to that a large photo of Cage and Duchamp playing chess, and you could spend hours in the booth.

Hazem Harb at Tabari Art Space

Photo credit: Ismail Noor

Tabari Artspace’s booth is dedicated to Palestinian artist Hazem Harb, whose work combines collage and installation through a constant engagement with archeology, mapping and displacement. The presentation draws on work from 2018 to the present, allowing different moments in Harb’s practice to dialogue with each other rather than forcing a single narrative.

Several pieces are from Reformulated Archeology (2018), in which Haab layered images of landscapes, anatomical forms, and Neolithic statues from across Palestine. Stripped of color and removed from their original context, these elements are reassembled into dense fields that echo the way artifacts circulate through the Western museum system: extracted, cataloged, and displayed far from their origins. The torso and face reappear, surrounded by thorn-like shapes, suggesting containment rather than preservation.

The Dubai-based gallery also brings map of victims (2025), in which Haab reassembles historical maps into abstract graphic shapes. The names of the erased villages are etched into clear glass, allowing the text and image to overlap and slide out of alignment. Drawing is here not as a neutral record-keeping but as an active tool of disappearance.

The center is and the middle (2024), a sculptural installation made from enlarged 3D-printed keys that replicate the keys to Hab’s home in Gaza and the keys to his own apartment, both of which were destroyed. Through repetition, the key represents displacement as ongoing rather than historical or symbolic.

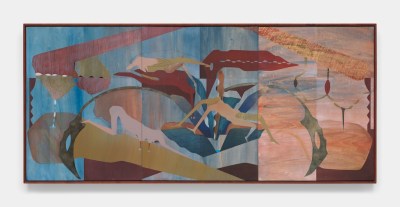

Maryam Hoseini at Green Gallery

Image source: Courtesy of Green Art Gallery

Dubai’s Green Art Gallery presents a new series of paintings by Maryam Hoseini, each spread across three or four painted wooden panels. Rather than functioning as discrete images, the panels form a continuous field that stretches across the wall, with bodies and landscapes appearing, breaking and re-appearing as your eye moves from one section to the next.

Numbers never break down into a single form. Repeat on all limbs. Architectural elements continue to emerge. The scenery disappears and appears. The orientation of the entire panel changes from horizontal to vertical, creating a sense of duration rather than direction. There is a quietly erotic quality to the work. From a distance they seem abstract, but a closer look reveals… more.

Hosseini’s work builds on her recent exhibition at the gallery, “Swells,” but the focus here is on how images accumulate meaning through delay. Each panel acts as a pause point, allowing the composition to recalibrate before continuing. The body functions both as a figure and as a structural element, anchored in a patterned surface that is both sensual and restrictive.

Amir Nour in Lawrie Shabibi

Image Credit: Seeing Things Photography by Ismail Noor

Lawrie Shabibi’s booth is dedicated to the work of the Sudanese-American sculptor Amir Nour, whose career largely lies outside the usual Western narrative of postwar modernism. The booth brings together sculptures and works on paper spanning several decades, providing a clear introduction to an artist whose work is simple in form yet rich in content.

The center is snake (1970), an early steel sculpture composed of 34 quarter-round tubes arranged in a low, undulating form. Made with precision from industrial materials, the piece reads differently as you move around it, changing from something architectural to a tool or container. There are two bronze sculptures next to it, toy doll (1974) and one and one (1976), which compresses symbolic and functional references into circular, interlocking forms. Both are loosely based on everyday objects from the early Nuer environment, including gourds and sudans jabanaa traditional coffee machine or water dispenser.

Also on the stand is a small collection of lithographs from the 1960s, created while Noor was a student in London. In works like this repenttraces of Diwani writing appear as marks rather than readable text, emphasizing rhythm and surface rather than language. Taken together, these choices speak directly to Noor as an artist working alongside, rather than within, Minimalism. The work is direct, material-based, and unpretentious, which allows it to fit comfortably into the fair’s quieter, more deliberate format.