January 15, 2026

Seoul – South Korean observers expressed mixed views on Wednesday after a special prosecutor called for the death penalty against former President Yoon Seok-yeol, accusing him of leading a rebellion through a failed self-government coup.

Even if Yin is sentenced to death in the February 19 verdict and the Supreme Court later upholds the original verdict, the likelihood of his execution remains slim. South Korea is considered a de facto abolitionist country and has never carried out an execution since December 1997, although about 60 death row inmates are incarcerated.

While largely symbolic, the harshest sentence against Yin could have significant consequences for a country long haunted by memories of military coups, dictatorships and repression that preceded 1987 democratization.

“While it is highly unlikely that Yoon will be executed, the special prosecutor’s request is rich in symbolism,” said Mason Rich, a professor of international studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. “The message is that the justice system and the government take the abuse of martial law and its potential for brutal abuse extremely seriously.”

Another expert echoed this sentiment, stressing the importance of sending a strong message that any threat to democracy will not be tolerated.

“Given the seriousness of the situation, requesting the maximum sentence seems appropriate, even though the likelihood of execution is almost zero,” said Benjamin Engel, an assistant professor of Korean studies at Dankook University. “This request and any subsequent sentence will demonstrate that Yoon’s self-coup attempt is completely unacceptable in democratic South Korea.”

However, British writer and journalist Michael Breen said that such a sentence was “to appease people’s emotions” and that the sentence may be reduced in the future, calling Yin’s execution “ridiculous.”

“In South Korea, sentencing in high-profile cases is not a rational question of proportionality,” said Breen, who has lived in South Korea for more than 40 years. “I thought from the beginning that prosecutors would ask for the death penalty. But I expected that eventually, when people stopped caring, he would be pardoned.”

Others expressed concern about the impact of social divisions.

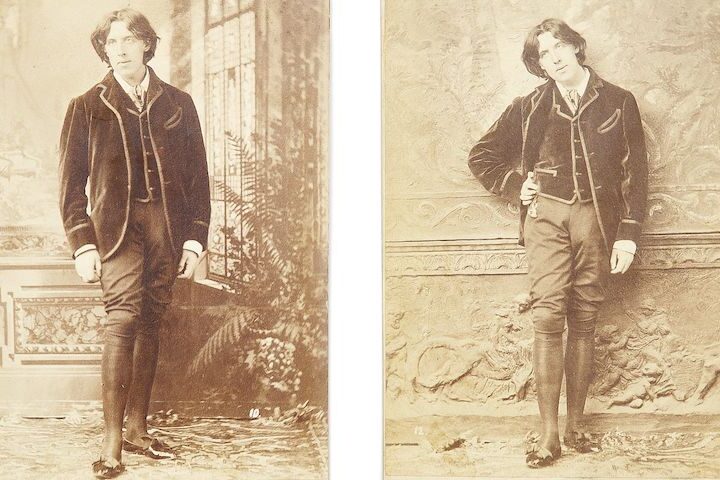

(From left): Mason Richey, professor of international studies at Hankook University of Foreign Studies; Benjamin Engel, assistant professor of Korean studies at Dankook University; Michael Breen, British writer and journalist. Photo courtesy of The Korea Herald

“Allegations of insurrection must be investigated thoroughly and independently, free of political influence,” said Spencer Waters, an American who works in communications in Busan.

“But seeking the harshest penalties could exacerbate polarization and turn the legal process into a token or vindictive one.”

A human rights group that advocates for the abolition of the death penalty also opposes the death penalty regardless of the severity of the crime.

“No one is above the law, including the former president, but seeking the death penalty is a step backwards,” Chiara Sangiorgio, Amnesty International’s death penalty adviser, said in a statement on Tuesday.

“Yin imposed martial law in December 2024, jeopardizing basic human rights and prompting prosecutors to seek his execution. While accountability is critical, the death penalty undermines the principles of human rights and dignity that the rule of law is supposed to protect.”

Impact on Korean politics

The special prosecutor’s request and the court’s upcoming ruling in February could reshape South Korea’s political landscape, just five months before local elections.

It could also deal a potential blow to the conservative People’s Power party ahead of June elections, as Yoon’s verdict could split the party.

“The death sentence may be Yoon’s final humiliation, but it may also make him a martyr among hardline conservatives,” Dankook University’s Engel said, noting that internal conflicts between moderates and extremists are likely to continue because the party has not completely severed ties with Yoon. “If the extremists win, the People’s Party could be in trouble in the June elections.”

Rich, of Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, said Yoon’s ruling may have a limited impact on overall voter sentiment. However, he noted that if a conviction leads to confusion or fragmentation in the Conservative Party’s message, it could slightly depress conservative turnout.