When artist Mia Westerlund Roosen debuted her conical sculptures, which undoubtedly evoked the penis, in 1982 at the “Leo Castelli 25th Anniversary Exhibition,” she did so as a form of feminist protest. This exhibition commemorates one of the most important postwar galleries, bringing together a pantheon of postwar American artists, the majority of whom were men. Westerlund Roosen is one of four women included in this exhibition of 29 artists.

However, inclusion does not translate into continued recognition and attention. Westerlund Rosen’s work did not spark controversy but was quietly marginalized. “They just kind of ignored me,” she recently told art newsrecalls her sculptures being dismissed as “simplified” or “eccentric.” In fact, what is read as deviation is a form of refusal, a refusal to remove the body from sculpture at a moment when dominant sculptural language prizes hard edges, industrial finishes, and emotional distance..

Just over a decade into her career, Westerlund Roosen’s practice has been defined by constant change, a trend she continues today. In the early 1970s, she chose to move on after realizing that working with resin would inevitably connect her to other artists such as Eva Hesse. “I don’t want to stay in a material where I’m always being interpreted through someone else,” she said. She turned to concrete and cement—heavy materials rarely used to depict the body at the time—and began modeling forms that suggested penises, breasts, and other reproductive anatomy. Over the years, she added steel, copper and lead, experimenting with how softer elements could push or reshape rigid molds. In the 2000s, she combined materials from the past and present, mixing cement with resin. “Cement is not really conducive to organic matter,” she said. “That’s what makes it fun.”

This approach provides a critical lens through which to view the artist’s current exhibition, “Past and Present,” at Nunu Fine Art in New York (through February 21). Spanning sculptures and paintings from the 1970s to the present, the exhibition traces Westerlund Roosen’s wide-ranging reflections on materiality and its relationship to the human condition.

“Mia Westerlund Roosen: Past and Present” exhibition, 2026, exhibition view at Nunu Fine Art, New York, showing the artist’s 1981 sculptures hot (background) and cone (prospect).

Photo Martin Seck/Courtesy of the artist and Nunu Fine Art

For dealer Nunu Hung, the exhibition is not about restoration or revision but resonates with our current moment. “Mia’s work exemplifies timeless artistic creation,” Hong said. “In this fast-paced era, the exhibition invites viewers to pause and reflect across cultures and generations, and to appreciate the humility these authentic works can offer.”

Upon entering, the audience will immediately see works like this: hot and cone (both 1981), both extend outward from the floor in muscular arcs, their elongated, tapered shapes protruding like curved penises. These sculptures are powerful: hot rose to nearly 13 feet tall while cone Extends to 5 feet at widest point. Made of wax-coated concrete, hot and cone Preserves mottled skin-like texture. The waxy covering has yellow and pink tones with dark scuff streaks that appear to have been applied and scraped by hand. Westerlund Roosen’s materials feel solid, even bruised. The sculptures look more grown than made, their scale amplifying a sense of vulnerability rather than monumentality.

Mia Westlund Rosen, Hot 11981.

Courtesy of the artist and Nunu Fine Art

This sense of movement can be seen in e.g. Hot 1 and heat 3 (both 1981), were not preparatory sketches for her towering sculptures but were later completed. Drawn in charcoal and brown pastels, these works on paper resemble afterimages, tracing the movements of trained dancer Westerlund Roosen as he reminisces. The lines loop and overlap, darkening as her body repeatedly moves through the space.

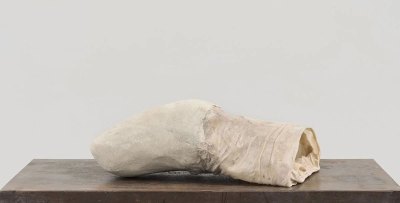

if hot and cone Establish the visual core of the exhibition, bag (2019) is almost reassuringly much smaller. Wrapped in light flannel and resin, its collapsed, elongated shape resembles a condom—soft, folded, stretched, even comically flabby. Viewed alongside sculptures made decades ago, bag Westerlund Roosen’s long engagement with masculinity becomes confusing: the aggressive extension has disappeared hot and cone. All that’s left is inner vulnerability.

Mia Westlund Rosen, bag2019.

Courtesy of the artist and Nunu Fine Art

“My work is often comic and menacing,” says Westerlund-Rosen. She has long been drawn to what she calls the grotesque—not as provocation per se, but as a form of expression that allows vulnerability and humor to coexist with strength. “I find weirdness to be beautiful,” she added.

Westerlund Roosen’s commitment to process was early influenced by the work of Lynda Benglis, whose pouring forms embrace gravity and chance. For Westerlund Roosen, they offer an alternative to the rigid orthodoxy of minimalism and the cold, impersonal decor. This orientation to material inquiry has been at the heart of Westerlund Roosen’s practice since her early days in the late 1960s.

asphalt (1978), for example, does not depict asphalt directly but rather aims to reconstruct the weight of its physical presence. Westerlund Roosen added layer after layer of charcoal, pastels and oil sticks to a 3-foot-by-2.5-foot sheet of paper, creating an almost entirely black surface—with splotches of yellow, red, and gray breaking through the darkness—that looks like a flattened concrete slab. asphalt This is not a preparatory study for sculpture or sculptural illustration, but a parallel inquiry into transforming the qualities and textures of industrial materials into something more tactile.

Mia Westlund Rosen, asphalt1978.

Courtesy of the artist and Nunu Fine Art

“Then and Now” is Westerlund Rosen’s first exhibition In partnership with Nunu Fine Art, the company is trying to find a new audience for the artist and reinvigorate her market. Although she has been exhibiting in New York since the early 1990s, first with Lennon, Weinberg, and then the Betty Cunningham Gallery (now defunct), she has not received as much attention as most of the other artists in the Leo Castelli 25th Anniversary Exhibition. When asked about the perception that she has become less visible over the past decade, she retorts. “I don’t agree with that,” she said. “I hold a solo exhibition every two years, and I invest as much energy as before.” She believes that what has changed is not productivity, but attention. “People stopped paying attention to my work.”

“It’s hard not to admire an artist like Mia who consistently produces outstanding work and remains committed to her practice,” Hong said. “She is undoubtedly one of the most respected artists of her generation. However, given the quality and scope of her career, she does not receive the recognition she deserves.”

Mia Westlund Rosen, huge waves1983.

Courtesy of the artist and Nunu Fine Art

Hong noted that she has priced hotThe towering sculpture now sells for $10,000, a figure in line with Westerlund Roosen’s current market price but well below the price of monumental sculptures by its male counterparts from the same period. Showing Westerlund Rosen’s work now is an attempt to recalibrate how it is viewed and valued, she said. Hong also plans to introduce the artist’s work to new audiences through her gallery in Taiwan. “I believe Asian collectors will respond to her sense of adventure and exquisite craftsmanship,” she said.

But as an artist, Westerlund Rosen is more concerned with what her art can do than her market. “Materials are important,” she said. “Concrete is not supposed to be soft, which is why I use it. I like to use something hard to hold something fragile.”

Still, Westerlund Rosen’s work is far from over. She continues to create large epoxy sculptures that are physically demanding and technically complex. If there is a thread through Westerlund Rosen’s practice, it is her refusal to take herself to heart. She never stops working or completely withdraws from the conversation, even when her attention shifts elsewhere. In an art world that values immediacy and constant visibility, her work insists on something slow and indecipherable: duration, touch and care over time.

“Maybe I’ll be popular when I’m 85, which is two years from now,” she said with a laugh.