Nimmo explains that ordinary Ghanaians regularly work with tailors and seamstresses to create custom garments from fabrics they commission end-to-end or purchase locally. Some may source ready-to-wear clothing from local boutiques or a handful of department stores in larger cities, but this is still relatively new. Others may participate in “National Friday Wear,” a government campaign launched in 2004 that encourages Ghanaians to swap Western corporate clothing for traditional fabrics and products on Fridays in an effort to drum up support for local industry.

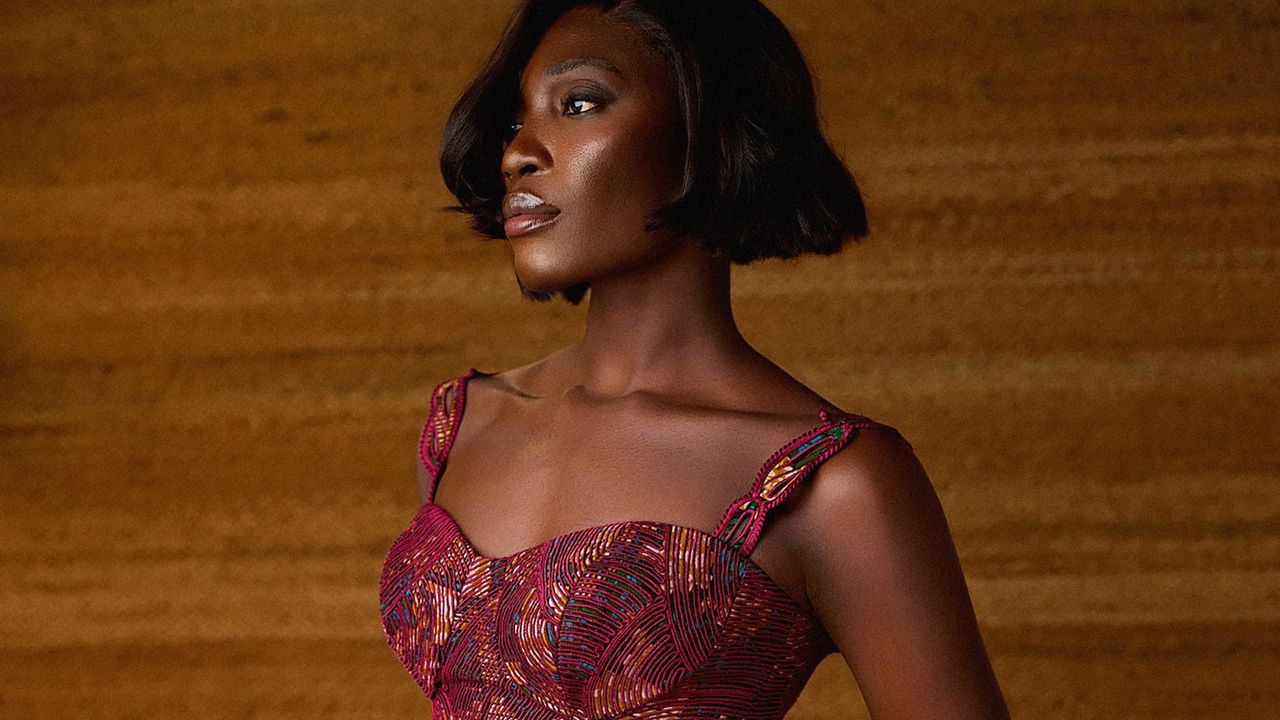

Most locals own a variety of ceremonial attires that they wear to weddings, funerals, and other events that require them to look their best. “That’s where most of their investment goes: buy some expensive local textiles and give them to a tailor or seamstress,” Nimmo said. Aisha Ayensu, founder of women’s clothing brand Christie Brown, adds that this is why, until recently, most Ghanaian fashion designers have adopted a business model closer to couture. The brand has become one of Ghana’s most famous luxury brands over the past 18 years.

But these practices were increasingly fragile and contradictory to the emerging fashion system. Minta says the biggest competition facing local textiles and more traditional fashion systems these days is the influx of low-priced second-hand clothing from the northern hemisphere. Markets like Kantamanto in Accra operate in various sizes across Ghana and receive tens of millions of second-hand garments from the northern hemisphere each week. It’s a double whammy for local manufacturers as the second-hand trade continues to bring in a flood of second-hand super-fast fashion.

While many Ghanaians still engage in custom-made and homemade clothing, the appeal of cheap ready-made clothing is growing, especially among younger generations who crave convenience and Westernized aesthetics, are influenced by what they see on social media, and are more detached from the connotations of traditional textiles. “You can’t compete with the Sheins of the world,” Minta said. “Fast fashion is not only destroying our textile trade, it’s also destroying local industries like seamstresses and seamstresses because they don’t get as many jobs anymore.”

Emerging markets that are grappling with the past

To understand the state of fashion in Ghana today, Nimo says you have to understand history. The first thing to note, he says, is that Ghana’s fashion system is influenced both by colonial rule and indigenous cultural practices, values and beliefs.

Take Ankara for example: Widely known today as African wax prints, they originated from Indonesian batik, which was mechanized by the Dutch during the colonial period and mass produced and exported to colonies across Africa. Minta noted that this process weakened the continent’s indigenous, labor-intensive textiles and accelerated the disappearance of traditional textiles. “Most ordinary Ghanaians don’t think of wax statues as relics of colonialism,” she said. From the 1960s to the 1980s, a select group of African women gained exclusive rights to sell new designs, earning the nickname “Mother Benz” or “Nana Benz” because the business was lucrative enough to afford a Mercedes-Benz car. “People made so much money from it that they no longer thought it was a bad thing that came from colonial trade,” she explains. Today, Mintah continued, the market is far less lucrative. As a flood of cheap, mass-produced knockoffs is imported into Ghana, local manufacturers and artisans are dwindling.