Why would Larry Gagosian want to host a blockbuster show of Jasper Johns paintings that had just opened at his gallery on New York’s Upper East Side? “First of all, because I wanted to see them,” he tells Alison MacDonald in a forthcoming article Gagosian Quarterly interview. It’s not a particularly lofty reason, but it’s at least an honest one—and it sets the tone for the entire conversation.

In this work, Gagosian speaks fluently about the formal characteristics of Johns’s art—the way the 95-year-old artist handles surfaces, the way he uses materials—but Gagosian generally doesn’t stop at the concepts behind the cross-hatch paintings in this show. Instead, Gagosian seems to speed up when you stand in front of these works long enough.

There is no doubt about the strength of the exhibition. Created between 1973 and 1983, these crosshatch paintings are not as austere as one might think. Up close, they are dense and delicate, their wax painting interrupted by occasional glimpses of newsprint or grit. Viewed from across the room, John’s traces have relaxed and the grid has softened. In several paintings, cross-hatching reveals half-figure shapes. The image is only resolved when you stop trying to think about it.

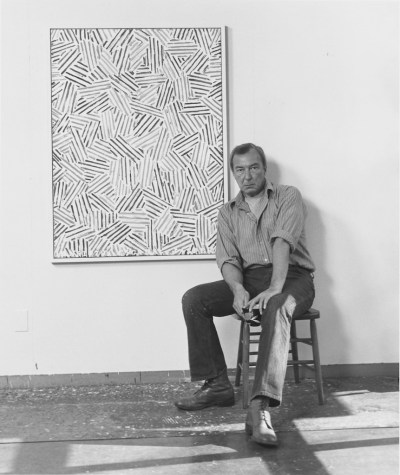

Jasper Johns in his studio, c. 1976–80

Hans Names

exist Gagosian Quarterly In interviews, Gagosian placed himself squarely within Johns’ orbit (despite the fact that Johns is still represented by Matthew Marks Gallery, as the artist has long been). When asked about his first encounter with Crosshatching, Gagosian did not cite a catalog or review article. Instead, he told a story.

In 1976, he casually mentioned that he was dating a dancer from Merce Cunningham’s company and followed her to New York. Through this relationship, he met Cunningham and John Cage, traveling with the company and even playing chess with Cage on the tour bus. It was during this period, before he met Johns himself, that Gagosian saw the Crosshairs paintings, which debuted in 1976, in Leo Castelli’s gallery. The real development of the art world came later. The memory is vivid, slightly romantic, and thought-provoking: Johns entered Gagosian’s story early on through proximity and experience. It also gives us a glimpse of salesman Gagosian, perhaps the second-best salesman mad MenIt was Don Draper who came up with the idea.

What’s impressive about Gagosian’s show isn’t its thesis—it doesn’t actually have a thesis—but the coordination involved in its production. There are assembled here Corpse and Mirror(1974), crying woman (1975), and most notably all six editions of Between the Clock and the Bed (1981), all of which are owned by a range of top collectors and museums, These include the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. This is the kind of thing that can only happen if a dealer is as powerful as Gagosian and has been around long enough — and the interests exchanged long enough — to make it possible.

exist Gagosian Quarterly In the article, Gagosian opens up about “digping deep” into loans and the rarity of getting a second chance at a show like this. No false modesty here, just an acknowledgment of size and access.

It is widely believed that the series arose directly from Johns’s encounter with Edvard Munch, whose paintings of 1940-43 Self-portrait. Between the clocks beside the bed. Prominently features similar themes to Johns’ cross-hatching. Since Munch painted the painting shortly before his death, Johns’ crosshair painting is often interpreted as a reckoning with death. But according to Gagosian, “It is a common misconception that Johns’s crosshairs were inspired by Edvard Munch’s self-portraits…But in fact, Johns had been exploring the crosshairs theme for years before meeting Munch. But when he did so, he painted six different versions of the Munch-inspired work.”

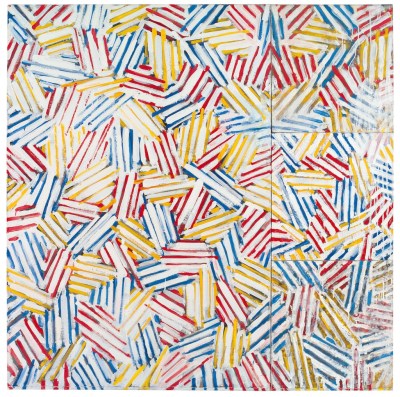

jasper jones, Untitled (1975). Eli and Edythe L. Broad Collection. © 2025 Jasper Johns/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) VAGA, New York. Photo: Jamie Stukenberg, Professional Graphics, Rockford, IL. © The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc., New York, 2025. Courtesy of Gagosian

Jamie M. Stuckenberg

The paintings are made up of short lines placed side by side again and again. Look closely and you can see the work: wax is pushed around, paint is dragged and squeezed, colors overlap and sometimes are scraped away. The team sat impolitely. Some are heavier and some are lighter. Some feel rushed, others cautious. You can tell where Johns changed his mind, or at least slowed down. Scraps of paper appeared in some places. Sand appears. There is nothing decorative about it.

Step back and the painting changes. The lines stop reading like lines and start moving together. Colors mix in the distance. What looked stiff up close became loose. Shapes that were not obvious before appear: shapes that suggest bodies, paths, or water flows. If you look too closely, they disappear again.

There’s another subtext here, and it wasn’t exaggerated in the interview. This is the final exhibition at Gagosian’s 980 Madison Avenue space, which opened in 1989 with Johns’ “Map” paintings. “That It was a very difficult show to put together,” Gagosian said, “but in the end, collectors and museums were generous and I was able to open this new space with these extraordinary works. It really put my gallery on the map, so to speak. “This year, the gallery will move to a downstairs space in the same building and wind down its upstairs operations. “So the crosshatch display feels like a nice bookend compared to starting with a map,” the dealer added.

Still, within the industry, people also interpret the show from a more pragmatic perspective. Although it is powerful, some may think The exhibition was seen as a not-so-subtle drama intended to lure 95-year-old Johns away from Matthew Marks. Could anyone expect less from an art dealer, let alone the actual art dealer Larry Gagosian? The show was instructive for Johns’s art and perhaps for Gagosian’s business practices.