January 30, 2026

jakarta – Tensions erupt at the palace in Solo, Central Java, as two half-brothers vie for the throne and rival family factions engage in a dramatic showdown over traditional and cultural authority.

The conflict escalated on January 18 when Culture Minister Fadli Zon visited the palace and issued a ministerial decree appointing the palace’s chief minister, Prince Tedjowulan, as Keraton Surakarta, custodian of the palace and overseeing public funds for the palace as a heritage institution.

Since the death of his older brother, Javanese royal Pakubuwono XIII, in November 2025, Prince Tedjowulan has been serving as a caretaker, awaiting the accession of a new king.

Rival factions of the late king’s two sons brought ladders to force open the ceremonial palace gates, with supporters of both sides pushing and shoving each other. The police stepped in to maintain order.

The handover was briefly interrupted for about 15 minutes after the two princesses raised their voices at Mr Fadli.

The event ended without a formal handover, just prayers, photos and traditional performances – reflecting the deep divisions within the palace.

King Pakubuwono XIII ruled in Solo (also known as Solo) for twenty years. After his death, his two sons from different wives claimed to be the legal heirs.

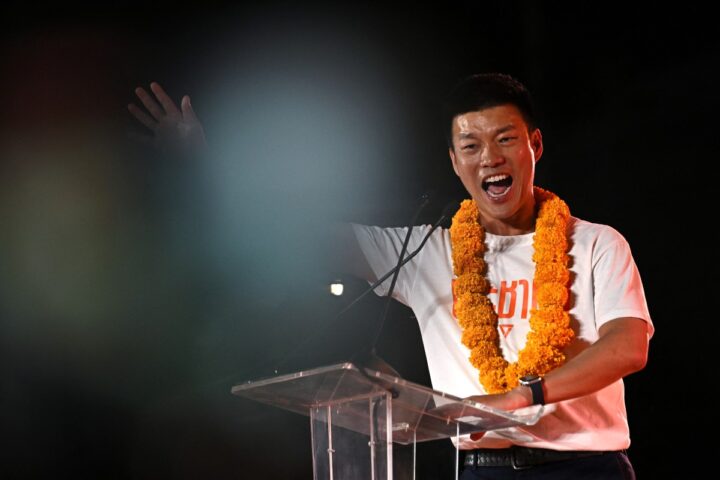

On January 16, the government sought to mediate this deeply personal family feud under public scrutiny. Vice President Gibran Rakabuming Raka had lunch with the two princes and their uncle, Prince Tejo Ulan, to discuss city and palace matters in an effort to ease tensions.

The younger son, Prince Purbaya, claimed that he was the legitimate heir. The late king officially appointed him crown prince in 2022. This was further reinforced by his mother’s status as queen – a factor that court tradition could prioritize over birth order when deciding succession.

Prince Hangabesh, the eldest son, rejected this reasoning. As the eldest son, he has stronger rights. Backed by the palace’s customary committee, the Lembaga Dewan Adat (LDA), his faction controls access to the ceremonial hall and thus day-to-day operations.

But since their father’s death, the Purbhaya princes have begun performing palace ceremonies, swearing oaths before attendants, and holding ceremonies in Solo, attracting huge crowds. His supporters say these rituals are decisive in demonstrating royal authority in Javanese customs.

Prince Purbaya also fulfilled his royal duties by submitting an official document called a Kekancingan to a mosque in January to reaffirm the loyalty and continuity of the royal family. Traditionally, this event was reserved for monarchs who delegated authority to local religious institutions.

On January 18, during the Indonesian government’s visit to Solo Palace, supporters of the royal family clashed. Photos: Screenshots from JOGJAKARTA.ID and SOLO.TIMES/INSTAGRAM/THE STRAITS TIMES

Meanwhile, Prince Hangabeishi told reporters after the culture minister’s visit: “I hope all discussions will go smoothly. I hope everyone remains united so that the government can play its role in helping the palace and its revitalization.”

He added that government decisions were above his authority and that he would continue to abide by palace traditions.

Two senior figures in the family have long shaped these rivalries: the brothers’ uncle, Prince Techoulan, the late king’s brother, and their aunt, the late king’s sister, Princess Morne.

In 2004, Prince Tedjowulan clashed with Prince Hangabehi and Purbaya’s father over the succession issue. The palace was locked in a long-running stalemate, with both factions claiming authority over ceremonial and administrative functions until a memorandum of understanding resolved the dispute.

In 2012, a settlement brokered by then Solo Mayor Joko Widodo confirmed the prince’s father as king, with Prince Techo Ulan serving as chief minister and acting as caretaker, managing palace affairs and maintaining the continuity of ceremonies.

Princess Morn rejected Prince Techoulan’s appointment, fearing that he would have too much power in his hands, and established the LDA to curb his influence.

She opposed this arrangement out of concern for succession plans and palace authority, arguing that according to palace convention, in the absence of a formal queen heir, the eldest son should inherit the throne.

“This is based on a prior written agreement: if the king dies, Chief Minister Prince Tejo Ulan will serve as the king’s deputy until the new legitimate king ascends the throne,” National Research and Innovation Authority political analyst Professor Vasisto Rahajo Jati told The Straits Times.

The history of Kasunanan Surakarta dates back to the 18th century. Under the Agreement of Giyanti of 1755, the Kingdom of Mataram was divided – separate courts were established in Surakarta and Yogyakarta (nearby cities also in Central Java).

[AfterIndonesiagainedindependencein1945mostmonarchslostpoliticalpowerSolowasincorporatedintotheprovinceofCentralJavaretainingonlyitsritualandculturalinfluence[1945年印度尼西亚获得独立后,大多数君主失去了政治权力。梭罗被并入中爪哇省,仅保留仪式和文化影响力。

In contrast, the Sultan of Yogyakarta was appointed governor in 1950, a position his family still holds today, making it the only region where a traditional monarch retains formal political power.

Prince Hangabesh is supported by the Lembaga Dewan Adat, the customary committee of Solo Palace. Photo: BERITASOLO/INSTAGRAM/The Straits Times

Today, Solo Palace follows centuries-old customs, with government involvement highlighting the delicate balance between ritual, tradition and administrative oversight. The government’s role is focused on protecting the palace as a cultural institution rather than influencing inheritance disputes.

“Of course, the government’s main interest is to protect cultural heritage, especially since Solo Palace is one of the central hubs of Javanese culture in Indonesia.

“If the conflict intensifies, it will have a significant impact on palace management,” Professor Vasisto said.

In 2017, the palace was declared a national cultural heritage area and has since received funding from the municipal, provincial and central governments.

“There has to be an accounting of these grants. There has to be a responsible party,” Fadli told reporters on January 19.

Dr. Sunyotto Usman, a sociologist at Gadjah Mada University, said the purpose of appointing Prince Tejo Ulan as caretaker was to provide a neutral mediation that respected customary rules.

He noted that even without political authority, the palace still had a cultural centerpiece.

“Javanese people still respect the royal nobility, even if it’s just customary, which helps preserve Javanese culture,” Dr. Sanyoto said.

Professor Vasisto said the palace’s role was not limited to ceremonial ceremonies. He explained that the royal title has evolved into a collective cultural identity marker for Javanese people, especially in Yogyakarta and Solo.

“Generally speaking, the legitimacy of the royal family and the sultan – with the exception of the Yogyakarta Special Zone – only serve as guardians of cultural heritage, so the central government has a role in protecting that culture,” he said.

The government’s appointment of Prince Techoulan may have clarified administrative responsibilities, but it does not resolve the question of who will be king.

Observers say the standoff between the two princes is likely to continue, with future clashes possible during succession ceremonies or government intervention. The outcome will shape Javanese identity and determine the legitimacy of the next monarch.

Professor Wasisto warned: “If this conflict is not resolved, it will affect the continuity of Solo Palace as the stable guardian of Javanese culture.”