Seydou Keïta (ca. 1921-2001), currently considered as the daddy of African digital photography, ran a hectic workshop in Bamako, Mali (French Sudan up until 1960) from 1948 to 1963, a duration of extreme makeover from country to city, early american to postcolonial, both because nation and in Africa overall. The countless individuals Keita photographed throughout those years stood for all sectors of Malian culture, consisting of Bamako’s social elite, man in the streets, wanderers, pupils, and armed forces police officers.

While Keita did design his topics– fanning a skirt below, readjusting a hand setting there, also giving European apparel, watches, bikes, automobiles, and radios as props– he likewise urged them to be energetic individuals while doing so. The appeal of his workshop amongst individuals of Bamako depends mainly on his ability in offering his jobs and permitting them to show up the method he wants: stylish, multicultural and, most importantly, contemporary.

In 1963, Keita was required by Mali’s post-independence socialist federal government to shut his workshop and started functioning as its main professional photographer. In 1991, his workshop pictures were displayed anonymously in the West for the very first time in a team program at the Gallery of African Art in New York City; a succeeding solo program at the Fondation Cartier in Paris in 1994– prints made from downsides delivered from Mali to France– was an experience, stimulating passion in Keita’s job and African digital photography generally. As worldwide popularity came, extra brand-new prints were developed, both throughout Keita’s life time and after his fatality. Larger in dimension and colder in tone than the initial photos, they are currently exactly how most modern visitors experience Keita’s photos.

For Western scholars and managers, Keita’s photos – which accompany the eve and very early years of Mali’s self-reliance – are both exciting pictures of self-defining people and crucial papers of African life at a minute of shift. For Keita’s Malian customers, the pictures imply far more than that. Pocket-sized and meant for individual usage, they represented life success, memorialized unique occasions and vacations, helped intermediators, and also functioned as amulets.

The event “Seydou Keïta: Tactile Lenses,” presently shown at the Brooklyn Gallery, concentrates on this last element of Keïta’s photos, highlighting the duty of self-fashioning in his development. Organized by visitor manager Catherine E. McKinley and Imani Williford, the gallery’s curatorial aide for digital photography, style, and product society, the event includes greater than 200 photos, consisting of downsides and classic prints, in addition to instances of apparel, fashion jewelry, and fabrics. The event runs up until March 8, and below’s an overview to Keita’s 5 significant jobs.

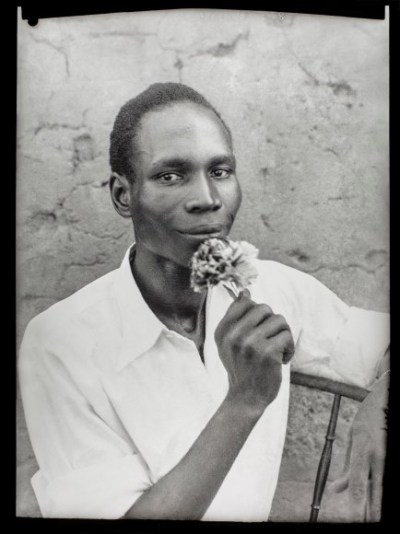

Untitled 1956

Picture resource: Thanks to the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, New York City.

Keita was birthed in between 1921 and 1923 in Bamako, after that the funding of French Sudan and later on Mali, which obtained self-reliance in 1960. At age 14, his uncle provided him his very first cam; in his twenties, while functioning as a woodworker, he apprenticed to Mountaga Dembélé (1919-2004), the very first black professional photographer to possess an effective image workshop in Bamako. In 1948, Keita opened his very own workshop before the home where he and his relations lived. He typically lacked incomplete movie to take pictures of himself, his spouse, kids, and family members (like the tender self-portrait over).

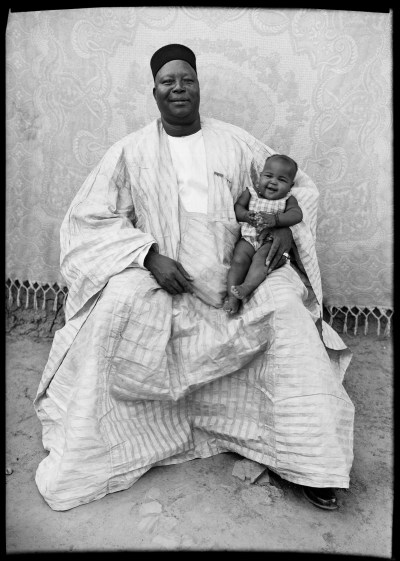

Untitled 1949– 51

Picture resource: Copyright © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta. Thanks to the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, New York City.

While the identifications of a lot of his topics are unidentified, the version was a buddy of Keita’s and, in addition to him, belonged to a well-dressed team of males called “gents.” He was holding a youngster on his lap and was using West African males’s apparel, consisting of drawstring pants, t shirt and Bubu A design of bathrobe, typically with luxuriant needlework, that is still commonly seen in the area. While European apparel and materials were preferred by rich Malians prior to The second world war, throughout the self-reliance period Bubu Ended up being a sign of quiet resistance to French manifest destiny. Behind-the-scenes, nonetheless, are the French damask sheets of Keita’s very own bed room.

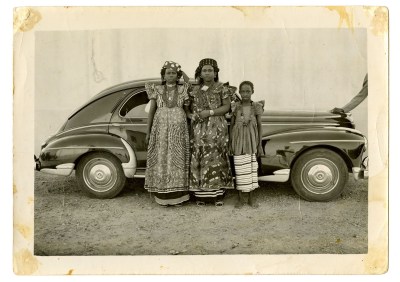

Untitled 1954

Picture resource: Copyright © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta. Thanks to the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, New York City.

Among the props Keita gave to his customers was his cherished Peugeot 203, among the only 2 automobiles left in Bamako and the various other coming from early american guv Edmond Louveau. The best front bumper of the cars and truck reveals Keita himself, backing up his cam and tripod. Equally as mid-century professional photographer Lee Friedlander typically included his very own darkness or representation right into his photos of American life, Keita below places himself as component of the social scene he records.

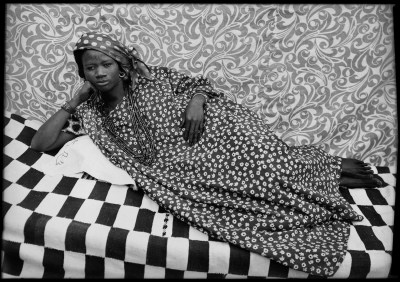

Untitled 1953– 57

Picture resource: Copyright © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta. Thanks to the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, New York City.

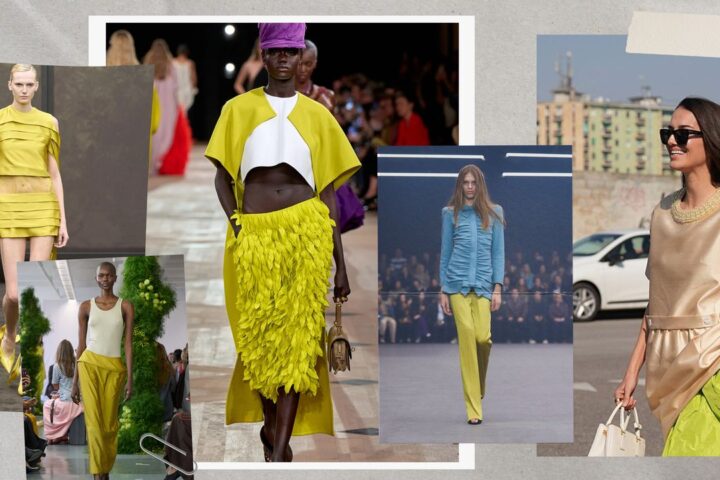

This picture, among Keita’s the majority of famous photos, in which the austere topic is nearly shed in a collection of contending patterns, is a research of opposing social pens. While the plaid covering on which she reclines is African, the highly formed textile behind her is most likely European. And, regardless of her flowery outfit Bubu The carnelian grains were standard, her watch was brand-new, and her headpiece was a headscarf hanging short on one side de Gaulle today’s style fads.

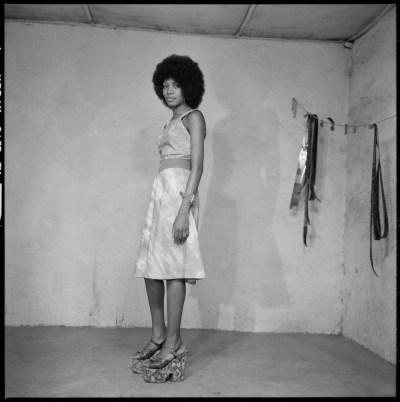

Untitled late 1940s to mid-1970s

Picture resource: Thanks to the Seydou Keïta household.

In this image, most likely taken after Keita shut his workshop, a girl sporting activities a vibrant afro, looming shoe, and a watch with a broad band and an extra-large dial. By the 1960s, a brand-new generation of Malians started to grow and came to be essential of their senior citizens’ attraction with imported items. However actually, in the 1960s and 1970s, they subsequently were brought in to African-American and British songs, dancing and apparel. This remains in straight comparison to the focus put on standard worths by Mali’s post-independence socialist federal government and its post-1968 armed forces program. Their vibrant defiant spirit was later on memorialized by Keita’s adherent, professional photographer Malick Sidibé (1935-2016) and others.