Editor’s Note: This story is part of Newsmakers, a new ARTnews series where we interview the movers and shakers who are making change in the art world.

Not every art dealer is in the mold of Leo Castelli, the aristocratic Italian who came to New York and created a market for artists like Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. His protégé Larry Gagosian, who now oversees a global empire, famously got his start selling posters on the street. The late Robert Mnuchin was a Wall Street trader before launching a gallery. Linda Goode Bryant ran a community center in Columbus, Ohio, before establishing New York gallery Just Above Midtown.

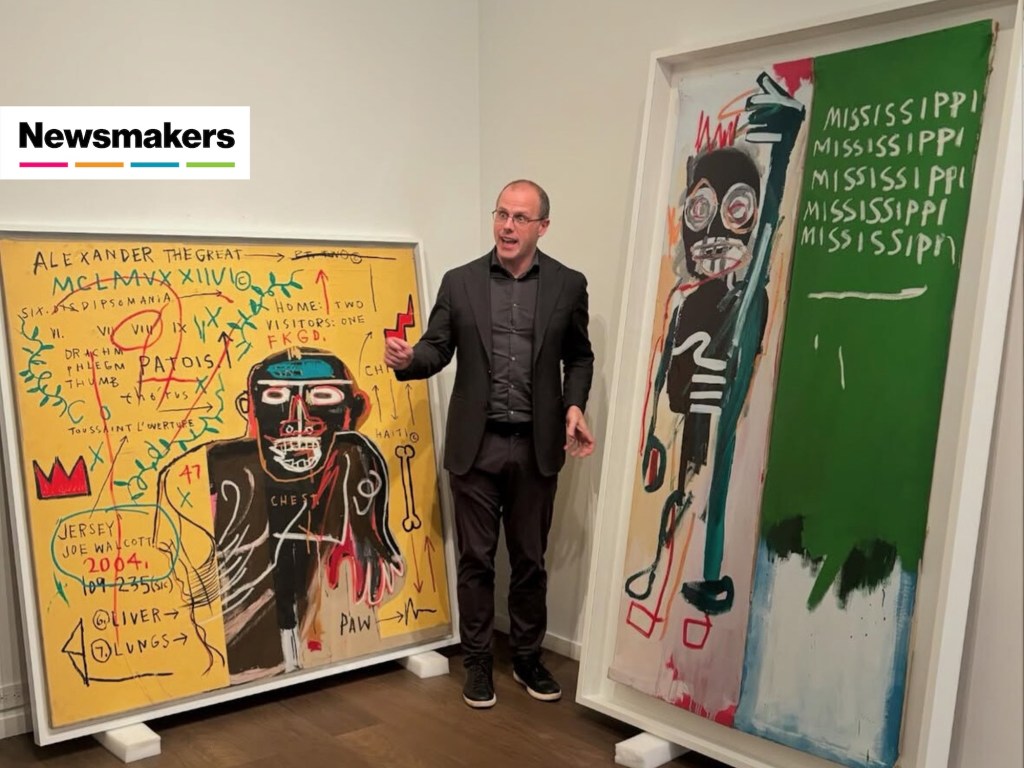

So what are the odds that a football player from a post-industrial Midwest town who worked in Navy intelligence in the Middle East before studying economics at Oxford can make it in the art world? That’s the CV of one Evan Beard, who is launching a secondary market gallery of his own, Beard & Co., on the Upper East Side (exact location TBD) after a few years running a similar operation for Masterworks, the $1 billion New York art-tech startup that fractionally sells blue-chip artworks and has been a mover in the auction world (even as it has earned some unfavorable press, both at ARTnews in 2022 and more recently at the New York Times).

Beard worked as a naval intelligence officer from 2006 to 2011 before developing art financing operations at Deloitte from 2012 to 2016, then moving to Bank of America in 2016 as managing director of national art services becoming head of specialty segments in 2020. While at BoA, he worked with major U.S. collectors, helping them to capitalize on their art collections for cash to invest in their businesses, be they in private equity, hedge funds, real estate, or entrepreneurial fields, as well as bringing clients’ collections to auction.

Beard joined Masterworks, an online investment platform founded in 2017 by serial tech entrepreneur Scott Lynn, as executive vice president in 2022, launching the company’s secondary market gallery, Level & Co., in an Upper East Side townhouse in 2023. Named for French financier and art collector André Level (1863–1946), the gallery is focused on artworks valued at north of $1 million and functions as “an art market merchant bank,” putting on display works by blue-chip historical artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Joan Mitchell, and Andy Warhol as well as pieces by contemporary artists such as Alex Katz, Yayoi Kusama, Ed Ruscha, and Christopher Wool.

“The intent was to sell works from the fund back into the market while also developing a robust secondary market brokerage business,” says Beard. “What ended up happening, though, is that Level became quite a profitable dealer/advisory model. We went very deep with a range of collectors who tended to build living collections. The gallery was quite profitable but my practice didn’t quite fit within the Masterworks business model.”

Beard & Co. will employ a half-dozen or so and aims to serve as a discreet private bank for collectors. Beard will advise on structuring art loans, auction guarantees and consignments, and estate planning. He also plans to use his knowledge of collectors’ holdings to discreetly find artworks for clients.

Evan Beard in his days playing football for the U.S. Naval Academy.

courtesy Evan Beard

“The art world is a more high-contact sport than football and full of more intrigue than anything I found in the Middle East,” he says.

The following interview is slightly edited for length and clarity.

Let’s go back to the start. How did a guy like you, not exactly to the manner born, get into the art game?

I come from Youngstown, Ohio, a post-industrial steel town, where I played football. I was recruited to the Naval Academy and played football there, and worked in Navy intelligence during the Iraq and Afghanistan war era. I was attached to a unit that did bilateral negotiations in places like Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, and then I was an Israel desk officer at the Pentagon. After doing the Great Books program at St. John’s University I went to Oxford, and was fascinated with the behavioral economics of places like the art market, where traditional principles of supply and demand don’t always apply. I got interested in the motivations of people to buy art, from status to legacy to financial return to aesthetics. And I wanted to get into that world.

I went into consulting and found a way to do some consulting on art projects. Bank of America had acquired US Trust and wanted to make that brand stand out a little more in the private banking space. I was the manager on a consulting team, and proposed that we build a team focused on the art world. I presented a strategy for an art group that would do things like manage museum endowments, lend against collections, and help with estate planning. And they said, Come join us and run it.

So, in 2015, I joined Bank of America Private Bank. The team is still there, and they have a $12 billion art loan book. A lot of big collectors bank with them, and they sponsor art fairs, like TEFAF.

And then how did you find your way to Masterworks?

I wanted to get into the art game—buying, selling, trading, advising—but no gallery or dealer would hire me. One of my clients was Scott Lynn, and they were in the early stages of building Masterworks, so I went there to build out the part of the flywheel that was selling the paintings. I was there for about a year, selling from the fund, but Masterworks is a self-directed retail investment firm and that brand was a little difficult for traditional collectors. I needed a different brand and business model, and the best way to do this was to set up a gallery on the Upper East Side.

My practice quickly became that of a dealer-advisor. Advisors are curatorial in nature and advise clients on what to buy. Dealers buy and sell for clients. The advisor-dealer is long-term greedy, and wants to help clients build a living collection. Most of my clients tended to be the people who banked with me at Bank of America. They had at least one eye on art as a capital asset, and were interested in how to unlock capital. We were very data driven. Our clients wanted us to find a work by this or that artist. It became a profitable business. So I made the decision that I will go and do my own thing. Masterworks will be a client of mine, and I will buy from them. They’re the biggest art fund in history. My focus is to have this private bank–style coverage model for collectors we go very deep with.

Evan Beard in his days as a naval intelligence officer.

courtesy Evan Beard

Based on ARTnews’ reporting, Masterworks is a bit of a chaotic, unregulated place that skirts legal and regulatory bounds. I realize Masterworks has to answer for Masterworks, and you’re still working with them, but is there anything you can say about the company?

Masterworks is a very innovative place. It’s the largest art fund in history. “Move fast and break things” is the tech mantra. It’s not a firm that came from the traditional art world, but it has made some big moves in that world.

But at Beard & Co., none of our clients come from a pure investment perspective. They want to own and enjoy the art but they do come from a perspective of wanting to deploy capital in efficient ways and get returns on their art. They have at least one eye on the capital performance and tend to be more transactional, wanting to borrow against their art, for example. The folks that would choose to work with us are not taking a purely curatorial perspective. That said, we are very analytical art historically. What does art need to be to represent our time? What’s a fad? We do not get on waitlists and buy what’s hot at the gallery. That will lead to bad returns. I mean, look, producing induced scarcity, as primary market galleries do, that’s a genius maneuver, where, with living artists, you create the idea that you can’t get access to it? That’s brilliant.

You mentioned to me that there are artists who are maybe getting prices that are a bit high compared to their established art historical value, like Avery Singer, who is young but has a $5.3 million auction high, as compared to which historical artists may be underpriced, such as Alice Neel, whose record is just $3 million.

Both great artists, but if you’re going to buy an Alice Neel, you can get a very nice one for $1 million, and she’s been a massive influence on another generation of figurative artists, a pillar for a generation of artists who look to her. In Avery Singer, you have a woman in her early thirties trading at $5 million. If you double that, you get into the territory of Matisse and Picasso. There’s nowhere to go from there but down.

Evan Beard.

courtesy Evan Beard

As you survey the art market today, with many midsize galleries closing but others expanding and new ones opening, with many different and conflicting signals about the state of the market, what do you see? Do you have any predictions for 2026?

We hit a cycle, from about when we came off the financial crisis of 2008–2009, when the art market was on a secular bull run, and the galleries’ mantra was that you need to scale to attract great artists. You need a global footprint, and have to put a ton of investment into infrastructure. Art fair investment was very high. People would literally run to the booth on day one. That boom cycle topped out in 2021 and for the last few years—it had to happen—we’re in a moment of rationality. If you have a global infrastructure with high costs, running a gallery became tougher. So you’re seeing consolidation. Some galleries that had five locations are paring back to two or three. You’re seeing mid-market dealers struggle. Fairs aren’t offering the same return. We’re back to a more normal market. We’ve gone from speculation in the ultracontemporary market to a demand for art that is canonized and has a secondary market history.

Everyone talks about having to expand the client base in the art market as a generation of collectors ages out and we can’t assume an interest in art among the next generation. Where do you find those new clients, geographically or in terms of what kinds of professions or industries they might be in?

I would say more than half of our clients bought their first painting with us. Wealthy people tend not to come in at a low level. They want to come in big, so we make sure they don’t make any mistakes. New clients are coming from the next generation of private equity and hedge funds, who have watched the Kravises and Leon Blacks and Ken Griffins collect and they’ve spun off and started their own firms.

But more interestingly, there’s a ton of quiet wealth in places like Oklahoma and Colorado and Texas. These are first-generation entrepreneurs who have either sold their company or are quietly producing very good cash flow. They are fascinated with art but slightly intimidated by the art world. We speak a layman’s language, not art-speak.

Look, I’m the most uncool person in the history of the art world. I have no style. So we try to be very relatable to them.

Who are some of the art dealers and galleries you look up to, and what do you find interesting about them? We just lost Robert Mnuchin, who was on Wall Street before he opened an art gallery. Is he someone you look to as a model? What do you think you can do differently from your predecessors?

The thing I find fascinating about secondary market dealers is they all have a unique way of doing it. Larry Gagosian is fascinating because he’s a savant when it comes to extremely high-class tastes as well as being an absolute bull in terms of the market. He has a market persona mixed with a really sensitive art-historical perspective. Mnuchin brought an old-world banker mentality. He was a very ethical guy. He loved working with clients discreetly and treated everyone with respect and dignity. I learn a lot from David Schrader about how to get things through the system and not try to maximinze every single deal. Michael Altman taught me how to talk about a painting and elevate it. Everyone has their own twist on things. I love meeting with other dealers and learning how they play this game.

You mention David Schrader, and he was in the headlines recently when he and Pace Gallery and Emmanuel Di Donna joined forces on a gallery, also to be located on the Upper East Side. What do you think a collaboration like that says about where the market is going?

One thing I learned very quickly is that you can only exist in this market by collaborating with other dealers. Many deals are done in partnership with other dealers who may have access to a work, and you have access to the buyer. The secondary market is a lot more collaborative than the primary market.

Those are three world-class dealers with complementary skills. Schrader is a banker, Di Donna is a museum-worthy art historical exhibition maker, and Glimcher is a global heavyweight. They’ll be a huge force in the market. They’re in competition but they’re collaborators. I may lend to them, they may get a Cecily Brown or a Joan Mitchell, artists who I’m very active with. Your competitors are also your collaborators. It takes a village to sell art sometimes.