January 2, 2026

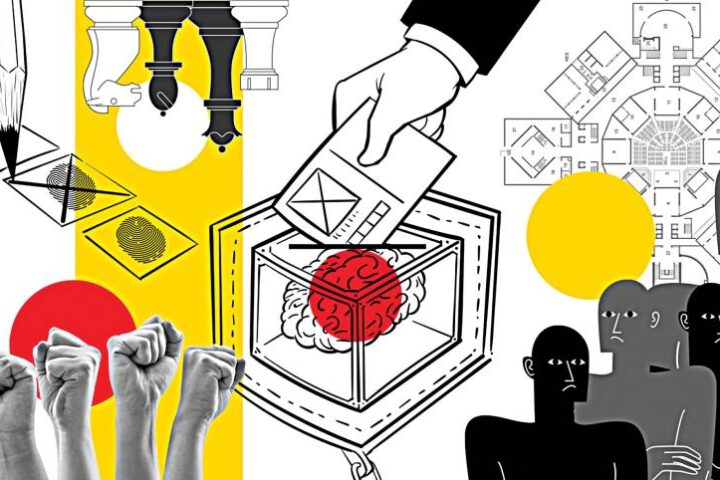

jakarta – This week marks Myanmar’s first so-called “general election” since a 2021 military coup, which took place under the shadow of civil war, mass displacement and widespread repression. The junta promotes elections as a path back to democratic rule. In fact, it was quite the opposite: it was a spectacle designed to purge authoritarian power through the language and image of democracy.

The 2025-2026 polls will be held in three staggered phases. This form reflected not administrative innovation but the inability of the military government to control the country’s territory.

Of Myanmar’s 330 townships, only 102 will vote in the first phase on Sunday. The second round will be held in 100 towns and villages on January 11, 2026, and the third round is scheduled for January 25, with an expected number of voters reaching 63. Nine communes still have no scheduled dates and 56 have been canceled entirely due to “security reasons,” a euphemism for ongoing conflict or loss of territory. In many areas, it is simply impossible to set up polling stations because the military junta no longer rules there.

The political sphere is systematically designed to guarantee predetermined outcomes. In January 2023, the military government introduced a new political party registration law requiring all political parties to re-register according to criteria designed to exclude their main opponents. In March 2023, the government dissolved 40 political parties, including the National League for Democracy (NLD), which won about 82% of parliamentary seats in the 2020 elections.

Only six political parties are allowed to field candidates across the country, including the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the National Unity Party, the People’s Vanguard Party, the Shan and National Democratic Party, the People’s Party and the Myanmar Farmers Development Party. Most contests have been limited to local contests, leaving federal Democrats with only token contests. Under these conditions, uncertainty is impossible. The outcome was not argued for but arranged.

There shouldn’t be any confusion. Where a ballot appears does not confer legitimacy. This is the consolidation of a dictatorship disguised as an election. Instead of holding elections where they should be held, the junta held elections only where they could be held. Participation is determined not by citizenship but by military influence. Any vote held in this environment would reflect the collapse of the state’s legitimacy rather than its renewal.

The space for dissent has been severely reduced. Media reports said more than 200 people had been charged for disrupting or opposing voting under a new law that carries severe penalties including death. Young people were jailed for anti-election posters; journalists faced intimidation; civil servants were forced to participate. Giving up is dangerous; criticizing is a crime.

The first round of voting was accompanied by violence. Explosions and air strikes were reported in several areas. A rocket attack in the Mandalay region injured three people, while in Myawaddy, near the Thai border, an explosion destroyed a house, killing a child and hospitalizing others. Soldiers have been deployed to “protect” polling stations, a move that resembles a systematization of control rather than public safety.

Behind every ballot box photo are communities living with grief, fear and exhaustion. People in Myanmar told me, “This election is just a show and it won’t change anything.” That’s not cynicism; This is clarity. They understand that elections held amid airstrikes, arrests and fear cannot express the will of the people. Myanmar’s exiled youth described the poll as a “comedy show” and a cruel parody of democratic aspirations.

However, some governments in the region may still be inclined to view these polls as progress. They must resist this temptation. Stability without justice is not peace; stability without justice is not peace. This is the normalization of oppression. Recognizing the legitimacy of such performances rewards violence as a path to power and suggests that democracy in Southeast Asia is optional and a matter of convenience rather than belief.

External actors, especially China, shaped battlefield dynamics through Lashio pressure and secret negotiations. While these initiatives may change influence, they do not bring security or dignity to civilians. Claims that these elections are a “pathway to peace” are pure fiction. For ordinary people, this is simply the next chapter of the five-year catastrophe.

ASEAN must stick to its principles. The Charter affirms respect for human dignity and democratic norms; Vision 2045 promises a people-centred, rights-based community. The EU must tell the truth clearly: these elections cannot be seen as the will of the people. It’s not interference, it’s integrity. Silence or congratulations would undermine ASEAN’s credibility and betray its own norms.

This moment calls for a reorientation of engagement. ASEAN must deepen diplomatic engagement, not with those who seized power by force, but with those who represent Myanmar’s democratic aspirations. Humanitarian aid must be expanded, not as an act of charity but as an affirmation of dignity, allowing displaced communities to retain options for their future and not become permanent victims of geopolitical paralysis.

To ASEAN leaders: Choose courage over complacency, principles over convenience, and people over power. Recognition must be gained through a process of empowering citizens, not spectacle designed to legitimize military rule. The people of Myanmar have paid an unbearable price for their hope for democracy, with thousands killed, tens of thousands detained and millions displaced. They deserve more than just being props in a show; they deserve to be heard.

As an Indonesian, I specifically call on the government of President Prabowo Subianto to stand with the people of Myanmar and refuse to legitimize this sham election. Let us lead not by claiming authority but by demonstrating integrity and showing that democracy in Southeast Asia is a shared commitment, not a slogan. Indonesia has shown before that democracy is not accidental but chosen, defended and renewed. We must now choose it again.

Democratic norms must be seen as the basis for regional legitimacy rather than as decorations worn when convenient. If ASEAN is to have a future worthy of its commitments, it must first deliver on those commitments in Myanmar. The credibility of our region and the possibility of a democratic Myanmar depend on this choice.

The author is the former Representative of Indonesia to the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (2019-2024).