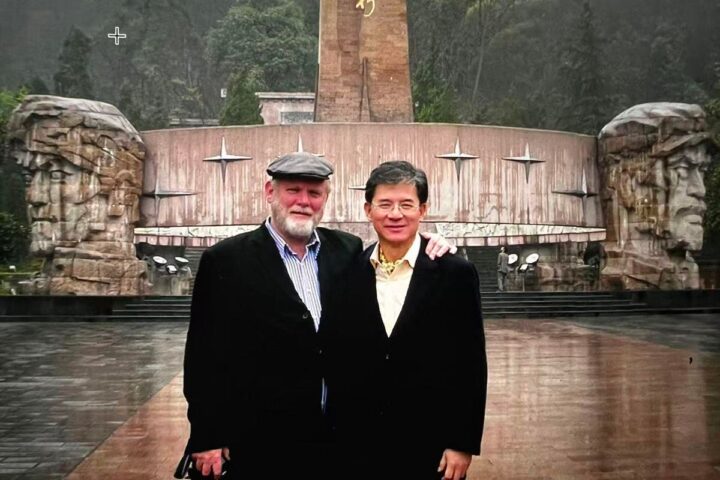

Senegalese and Chinese workers watch a ceremony at the construction site of the China-funded National Theater in Dakar during the visit of Chinese President Hu Jintao and Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade on February 14, 2009. Joint projects such as these have defined the Belt and Road Initiative, but are now causing backlash and repositioning.

AFP via Getty Images

Over the past decade, China has built extensive transportation, energy and industrial infrastructure through its Belt and Road Initiative, solidifying its position globally and becoming a major trading partner and creditor by the mid-2020s. However, the Belt and Road model, centered on state-backed loans, opaque contracts and the export of China’s excess industrial capacity, exposed the structural weaknesses that drove the creation of Belt and Road 2.0. Rising debt burdens, environmental damage, limited involvement of local businesses and increasingly negative public sentiment have created a need for alternatives.

The United States has recognized that competing with China in infrastructure is unrealistic and has therefore adopted an asymmetric strategy. Rather than emulating Beijing’s capital-intensive approach, Washington has leveraged its comparative advantages in soft infrastructure, technology, standards, and institutional capabilities. Instead of building hospitals or reservoirs, America could train nurses or engineers. The G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) has become the main vehicle for this strategy to compete with China.

While the advantages of PGII and BRI are emerging through international competition, energy infrastructure and dynamics complicate previous assumptions about BRI and PGII. The Trump administration’s unabashed embrace of hydrocarbons has translated into a public desire to accelerate funding for energy infrastructure as part of U.S. foreign policy, thus violating the asymmetric underpinnings of PGII. China is trying to reduce its dependence on fragile energy imports but is more interested in building dependence on Chinese green technology exports and Chinese regulations. This awkwardly puts Chinese and American energy strategies at odds with their own global infrastructure plans.

The forefront of competition between China and the United States

There is no better bellwether for the competitive position of the United States and China than Central Asia, especially when it comes to energy infrastructure. Central Asia is where China first proposed the Belt and Road Initiative and launched Belt and Road 2.0, and it is no coincidence that Central Asia is the first place Xi Jinping visits after COVID-19 ends. Historical tensions in the region also force Beijing to proceed with caution. For the United States, Central Asia is besieged by Russia, China, Iran, and Afghanistan, while Europe and India are close neighbors. This makes Central Asia key to U.S. geopolitical initiatives.

Infrastructure, especially energy infrastructure, remains a core tool of geoeconomic influence in Central Asia, beyond regulated construction or high technology. China continues to prioritize building roads, railways and pipelines to ensure export routes and energy supplies. In contrast, the United States and its G7 partners have focused on optimizing existing infrastructure, reducing logistical bottlenecks, and integrating Central Asia into global supply chains that bypass Russia and China.

The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) or “Middle Corridor” has become an important artery connecting Central Asia and Europe via the Caspian Sea and the South Caucasus. After the geopolitical shocks of the early 2020s, the Northern Corridor through Russia became commercially and politically unsustainable for many companies, which greatly increased the strategic value of the trans-Caspian route.

Traffic volume along the middle corridor is growing rapidly. In the first 11 months of 2024, the freight volume along the TITR reached 4.1 million tons, a year-on-year increase of 63%, and the container transportation volume increased 2.6 times, exceeding 50,000 TEUs. However, much of this growth was driven by Chinese transit: freight volumes from China to Europe increased more than fourteen times. In effect, Beijing has used Western-backed upgrades to integrate the Middle Corridor into the broader Belt and Road ecosystem.

This is an unusual situation. Often, Western actors exploit China’s infrastructure to advance their own interests. Washington responded by seeking a functional rather than a physical repositioning of the corridor. In 2025, the United States will include TITR in Trump’s international peace and prosperity line. The TRPP is a U.S. corridor through Armenia that connects regions of Azerbaijan and is part of the Azerbaijan-Armenia peace process and a complementary route to the TITR.

The TRIPP framework aims to shift the purpose of the route from transit through China to the export of Central Asian resources and manufactured goods such as uranium, tungsten, fertilizers and agricultural products to Western markets. TRIPP also emphasizes European energy security by bypassing Russia and Iran, and promotes the adoption of digital logistics systems in line with the West as an alternative to China’s LOGINK platform.

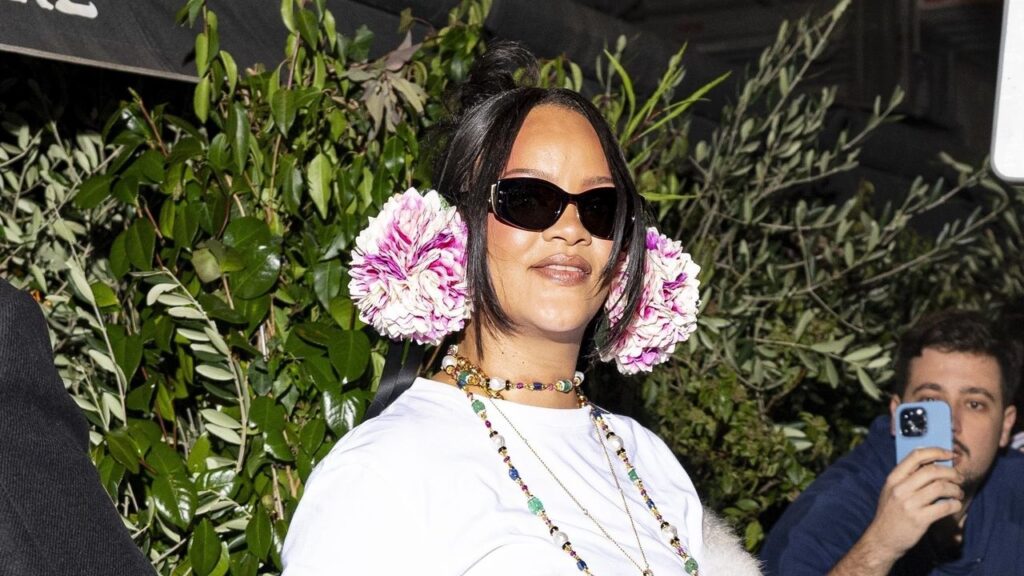

On August 26, 2024, a Chinese military nurse on board the China Peace Ark hospital ship, which provides humanitarian medical services between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa, conducts an exercise in the Port of Cape Town. Despite China’s belated efforts to embrace U.S.-style service diplomacy, the observable impact still lags behind Washington’s.

AFP via Getty Images

dueling asymmetric strategy

Given the high cost of building ports and railways from scratch, U.S. and EU efforts have focused on soft infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Trans-Caspian Trade Route Initiative has emerged as a key tool, advancing a joint action plan focused on three priorities: harmonizing customs procedures, digitizing cargo documentation and tracking, and harmonizing end-to-end tariffs across the corridor. Together, these measures address inefficiencies that often cause shipments to be delayed beyond actual transit times, while increasing transparency and reducing the risk of corruption.

The contrast in financing models is equally stark. Belt and Road projects mainly rely on sovereign loans from Chinese policy banks or industry-wide banks, usually backed by state guarantees or resource collateral. In contrast, PGII seeks to mobilize private capital through blended financing, grants and risk mitigation instruments deployed by institutions such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the Export-Import Bank. This approach reduces sovereign debt risk while making projects more commercially viable in the long term, but at the cost of slower project mobilization.

Standards and transparency further differentiate the two modes. PGII and G7-backed initiatives implement strict anti-corruption safeguards as well as environmental and social assessments. In contrast, projects in China tend to be subject to closed contracts, limited public disclosures and weaker environmental requirements.

The second major area of competition is digital. China is promoting the Digital Silk Road by exporting surveillance technology, 5G infrastructure and cloud services. Huawei benefits from low costs and preferential financing to dominate the Central Asian telecommunications market. In response, the United States proposed a model based on open standards, supplier diversity, and digital sovereignty.

Promoting open RAN architecture, which allows operators to mix equipment from multiple vendors, has become central to this effort. Uzbek mobile operator Perfectum, backed by Western funding, chose Nokia, setting a precedent by excluding Huawei from the core of its network and demonstrating that diversification is both politically and commercially viable.

Satellite communications further change the balance. By reducing reliance on terrestrial cables traversing Russia or China, satellite internet directly strengthens regional information sovereignty. Following the rural education pilot project, Starlink was officially launched in Kazakhstan in August 2025, and Uzbekistan is expected to follow in 2026.

Competition now extends to data storage and processing. China is investing in data centers and artificial intelligence infrastructure under Digital Silk Road 2.0, while the United States is working to integrate Central Asia into the global cloud ecosystem led by Microsoft, Google and Amazon. In late 2025, Kazakhstan announced a $3.7 billion partnership with a consortium of U.S. technology companies to develop artificial intelligence infrastructure and train experts, in line with President Tokayev’s ambition to transform the country into a fully digital economy.

U.S. economic policy toward Central Asia from 2026 to 2030 increasingly emphasizes partnership rather than aid, focusing on job creation, technology transfer, and sustainable growth. This approach contrasts with the Chinese model, which has intensified debt dependence and commodity specialization.

energy imperative

Geoeconomic activity in commodity-rich Central Asia tends to focus on energy and energy infrastructure. Frontier areas such as energy and critical minerals represent some of Washington’s most tangible successes. Through the C5+1 Critical Minerals Dialogue, the United States prioritizes the development of uranium, tungsten, lithium and rare earth reserves in Central Asia. In November 2025, Cove Capital reached a US$1.1 billion agreement with Kazakhstan’s Tau-Ken Samruk to develop a tungsten mine, and received strong support from the Export-Import Bank and DFC. Given that China supplies about 80% of the world’s tungsten, establishing a major alternative source is a strategic gain, especially since processing and value addition will take place within Kazakhstan.

Despite these advances, China remains the largest creditor, with much of the credit tied to energy infrastructure in several Central Asian countries. This creates ongoing vulnerabilities. These countries, especially Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, where Chinese loans account for about a third of their external debt, face limited fiscal space and heightened political risks. Although Washington cannot directly refinance this debt, it is trying to offer an alternative growth model centered on private investment rather than sovereign borrowing.

The B5+1 platform has become a key mechanism in this regard. The upcoming forum in Bishkek in February 2026 will focus on areas such as e-commerce, tourism and agribusiness, which create jobs faster and are less capital intensive than large-scale infrastructure projects and help alleviate social pressures from population growth.

The main challenge facing the United States remains scale. The US’s measures are targeted and selective, while China’s presence is systemic. Long-term success will no longer depend on memos but on quick, visible implementation that demonstrates commercial viability. Nonetheless, the United States is increasingly able to engage China from a position of relative advantage, supported by a growing alliance of global and Central Asian partners who view U.S. engagement as a guarantor of sovereignty and a tool for strategic maneuvering in the face of global instability.