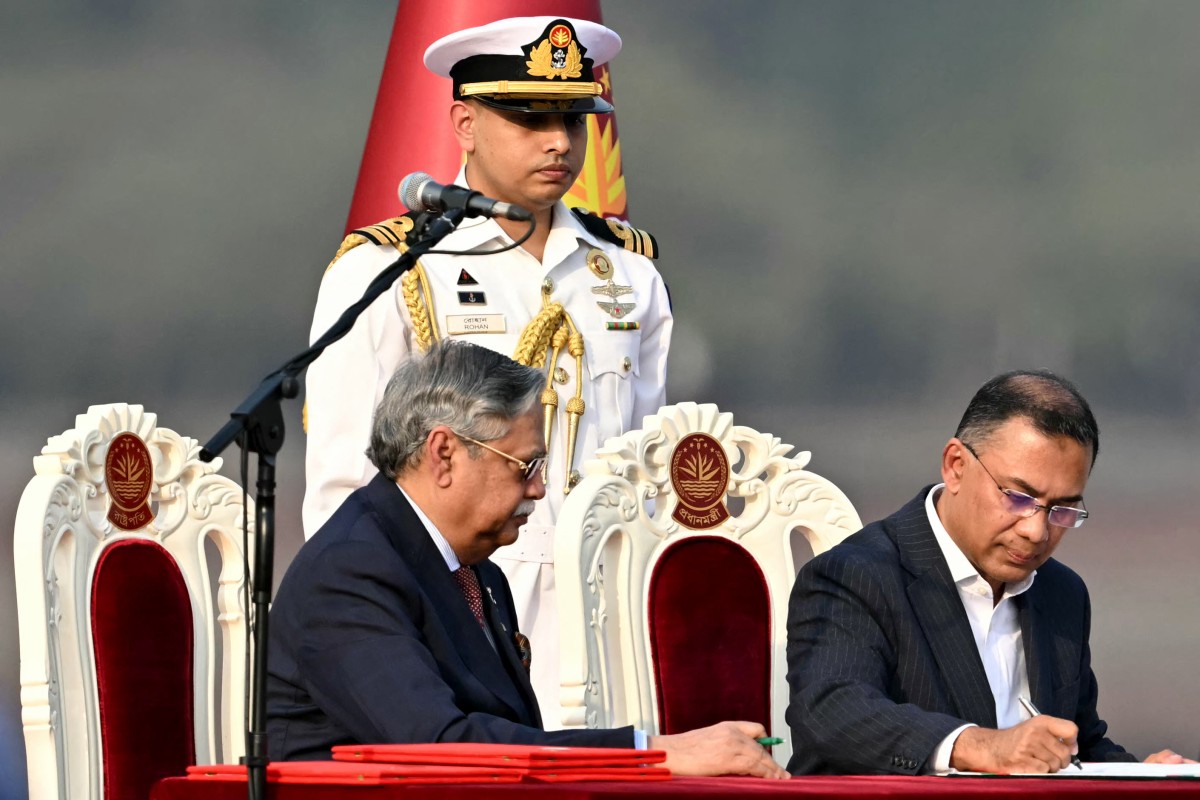

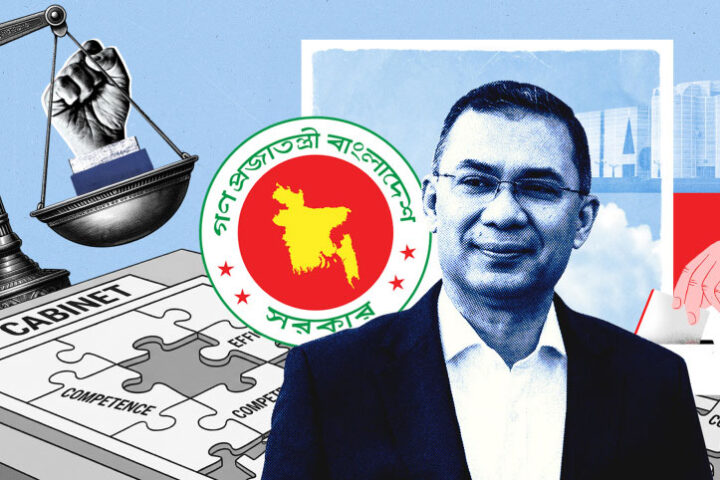

Singapore – As a mediocre student in Dhaka, Prime Minister Tariq Rahman was often teased for not being the sharpest knife in the drawer. Now at the head of the country, Bangladeshis will pray that their untested leader – a recent college dropout who recently returned to his country after 17 years in exile – can learn more quickly.

Mr. Rahman, 60, faces many issues at home and abroad that require urgent attention and flexibility.

It does help because not only does he have the pedigree, but he also has a strong mandate.

He is the son and political heir of the late Lady Khaleda Zia and her husband Ziaur Rahman. Zia served two terms as prime minister and Ziaur Rahman was a former military leader and president of Bangladesh who was later assassinated.

In 2018, his Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which he led in London, won 209 of the 299 seats in the national legislature after his mother was imprisoned by the Awami League regime of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wajid.

Jamaat-e-Islami of Bangladesh ranked second with 68 seats. The two major coalition parties gained some seats, while the remaining seats went to smaller parties and independent parties.

While the two-thirds sweep was impressive by any standard and was hailed as a landslide by global media in their enthusiasm for the broad secular institutions that govern the country with the world’s fourth-largest Muslim population, it underestimated several factors that had nothing to do with Mr. Rahman’s charisma or abilities that were key to victory.

Chief among them was that the once-entrenched Awami League, the party that won Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, was banned from contesting elections by the interim government of chief adviser Muhammad Yunus. After Hasina fled to India in August 2024 due to public rebellion, Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus took over running a caretaker government.

Under Professor Yunus’ watch, the Awami League was suspended under anti-terrorism laws and the Election Commission removed it from the list of officially registered political parties eligible to contest the polls. Hasina was also sentenced to death in absentia for “crimes against humanity”.

Professor Yunus and Hasina have a history of mutual unease. He won her a Nobel Prize (she had hoped to win it herself for solving the unrest in the Chittagong Hill Tracts) and later briefly toyed with the idea of forming a political party.

Less well known but crucial to the BNP’s success, the resurgent Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, long reviled for supporting Pakistan when the former East Pakistan split to form the new state of Bangladesh, failed to field a female candidate in the February polls.

Bangladesh is a rare country in South Asia where the gender balance favors women.

In addition to students, women were a powerful force in the Monsoon Revolution that overthrew Hasina. Solidarity’s patriarchal attitudes, including comments by some key figures linking women in the workplace to “moral turpitude”, led many to switch their votes to the BNP.

Mr. Rahman has spoken at 64 rallies, often bringing his wife and daughter to the stage, to his benefit.

Public sympathy for the death of his mother, Khaleda Zia, who died in a Dhaka hospital on December 30, 2025, undoubtedly also contributed to the BNP’s wave.

political pressure cooker

Mr. Rahman now faces significant challenges.

Politically speaking, the first step is to stop the General Assembly and its well-oiled machine. Jamaat, once marginalized, has now become fully mainstream in Bangladesh. Not only did it win nearly a third of the national vote, it is now also the main opposition party, with 68 seats in the legislature, compared with its previous best of 18 seats.

The referendum seeking ratification of the so-called July Charter, held to coincide with the legislative elections, received a resounding “yes” vote and, if implemented, would bring considerable influence to the General Assembly. That’s because a new 100-seat upper house will be formed within 270 days, with seats allocated based on national vote shares.

While not a mirror image of India’s booming Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) or its political wing, the Bharatiya Janata Party, functional similarities to the RSS, such as organizational discipline and a tendency to lean toward a particular religious identity, make Jamaat a lasting force in a country that might easily shed its predominantly “Bengali” identity toward a more Islamic identity.

More importantly, the charter strengthens the power of the president and reduces the concentration of power in the office of the prime minister.

In addition to the inevitable resurfacing of issues from the controversial past that required Rahman to leave Bangladesh, Mr Rahman will soon need to contend with pressure from within Bangladesh and from key neighbor India to allow the Awami League to re-emerge, even though the party is currently denounced for its violent final years in power.

The word coming out of Dhaka salons is that in order to negate the Awami League, despite the fierce competition between them, they have helped fill the BNP’s electoral coffers – which have been depleted by a long absence from power. Mr. Rahman needs to return the favor.

The economy is showing serious trouble. Bangladesh’s economy, which once enjoyed impressive growth, has slowed sharply, plagued by inflation and structural weaknesses. Although the Yunus administration has done much to clean up the banking system, investors complain about the uncertainty of the political environment and foreign investors are cautious.

Reset relationships with allies

From a geopolitical perspective, Mr Rahman needs an urgent rebalancing after Professor Yunus made a series of decisions seen as aimed at baiting New Delhi.

These include inviting China to participate in infrastructure projects near the narrow strategic Siliguri Corridor that connects India’s hinterland to seven northeastern states, and reports that a World War II-era air force base near the “chicken’s neck” may be revived with Chinese help. India reportedly responded by moving missile squadrons closer to the corridor.

The interim government also hosted a series of visits by Pakistani ministers and defense and intelligence officials, highlighted by Professor Yunus’ meeting with the Chairman of Pakistan’s Joint Chiefs of Staff in October 2025. Pakistan is reportedly in advanced negotiations to sell JF-17 Thunder aircraft to Bangladesh.

In addition, there is the United States to deal with. Hasina has repeatedly said the United States had tried to overthrow her because she was unwilling to lease Sint Maarten, an island near Myanmar, to U.S. forces. This not only worries China, which has deep interests in Myanmar, but also strains the bilateral relationship between India and the United States.

Mr. Rahman has no shortage of geopolitical pressures to contend with. While he is expected to maintain stable relations with China – Prime Minister Li Qiang sent a congratulatory message – Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s outreach suggests that New Delhi is willing to ignore past suspicions of the BNP and at least correct its over-reliance on the Awami League to achieve its geopolitical goals.

Mr. Rahman’s reciprocal gestures and commitment to seek constructive engagement with India, even as he pursues a “Bangladesh first” line, demonstrate a maturity and awareness of geopolitical realities that Professor Yunus appears to have failed to achieve.

This should be good for Bangladesh. Sri Lanka’s decades-long nightmarish insurgency began with ignoring this reality, for which it paid a heavy economic price. As it strives to achieve middle-income status, Bangladesh, which is surrounded by India on three sides, cannot ignore New Delhi’s sensitive issues.