February 16, 2026

Seoul – YouTube’s “silver play button” has become an unlikely new status symbol in South Korean politics.

As lawmakers seek more direct ways to reach voters, the silver button awarded to channels with more than 100,000 subscribers has become a sign of success.

But the shift to direct communication brings both political opportunities and hidden costs.

Lawmakers in the 300-seat National Assembly are increasingly using U.S. video platforms, some of which have attracted half a million subscribers, to bypass traditional media and speak directly to voters.

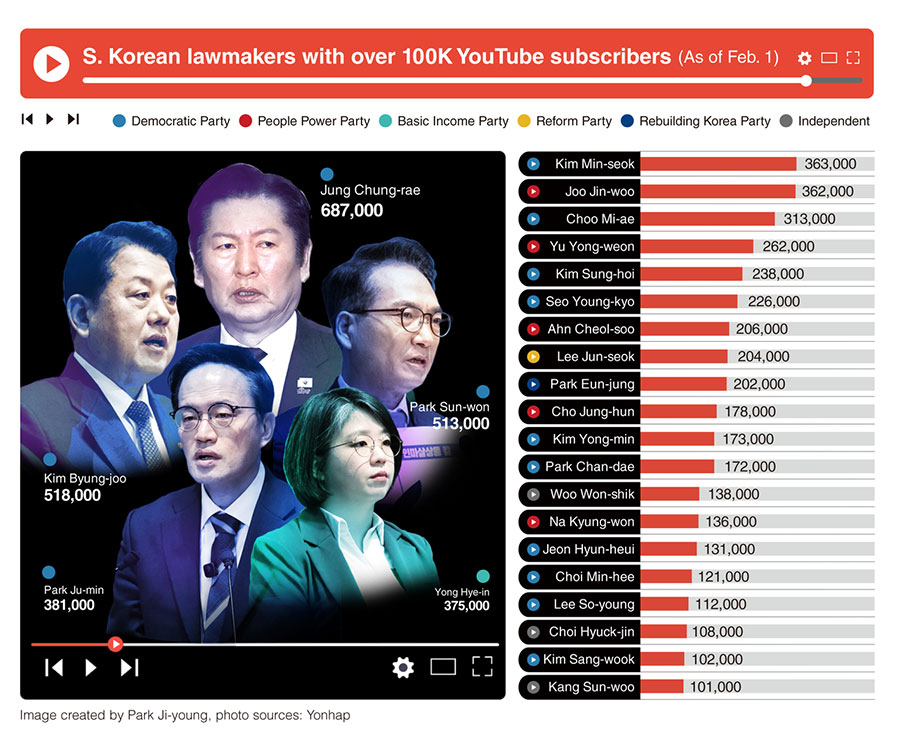

Estimates by The Korea Herald based on public YouTube data show that as of February 1, 25 South Korean lawmakers have more than 100,000 subscribers and are eligible to receive silver play buttons. Of those, 19 were from liberal or left-leaning parties and six were from conservatives.

Rep. Chung Chung-rae, a four-term member of the National Assembly and Speaker of the Democratic Party, topped the list with 687,000 subscribers, followed by Rep. Kim Byung-joo and Rep. Park Sun-won, both with more than 500,000 subscribers. Other Democratic Party lawmakers with large followings include Reps. Park Joo-min and Rep. Choo Mi-ae, both of whom have more than 300,000 subscribers, while Rep. Yong Hye-in of the minor party Basic Income Party ranks fifth with 375,000 subscribers.

Among the conservatives, first-term National Assembly member Chu Jin-woo leads the People’s Power Party with 362,000 votes, followed by Reps. Yoo Yong-won, Ahn Cheol-soo, Cho Jung-hoon and Na Kyung-won. Rep. Lee Jun-seok, chairman of the conservative Reform Party, also has more than 200,000 subscribers.

Subscriber numbers have little to do with seniority: of the 25 MPs with silver play buttons, eight are first-term MPs and seven are serving their second term, underscoring how digital influence depends more on content and timing than political rankings.

But experts warn against mistaking online participation for broad public support.

“A key challenge for democracies around the world will be understanding how political actors adapt to these platforms, and whether they can do so without allowing a small, vocal minority to define the political debate,” said James Bisbee, associate professor of political science at Vanderbilt University.

YouTube activity by South Korean politicians surged during the crisis triggered by former President Yoon Seok-yeol’s attempt to impose martial law in December 2024. The incident led to a surge in viewership, especially on the channels of liberal lawmakers.

On the evening of December 3, as the crisis unfolded, several liberal MPs live-streamed their activities in the National Assembly and confrontations with soldiers deployed in the building. In the days that followed, Reps. Kim Byung-joo and Park Sun-won co-hosted widely watched radio programs that included unprecedented live confessions from senior military figures.

In separate live broadcasts on December 6, former Army Special Operations Command Commander Kwak Jong-geun and former Capital Defense Command Commander Lee Jin-woo publicly apologized for their roles in the crisis. Guo’s admission that he received orders from Yoon to “drag” people out of parliament became key evidence supporting accusations that Yoon was attempting a self-coup. These broadcasts remain the Kim channel’s most viewed live videos since its launch in June 2020.

“People are deeply alarmed by the serious threat to democracy,” Park, a first-term member of the National Assembly and a former deputy director of South Korea’s intelligence agency, told The Korea Herald. He attributed the sharp increase in subscribers in December 2024 to the public’s “hungry for accurate information and fact-finding amid political turmoil,” adding that the response reflected “the strong will of the Korean people to defend democracy.”

King, a former Army general turned congressman, echoed that assessment. An official in his office said the focus on political content comes as “public anxiety over political crises increases,” adding that receiving the silver play button symbolizes “a strong commitment to communicating directly with the public.”

However, not all success stories come from the liberal camp. People Power Party Rep. Chu Jin-woo drew the audience to criticize then-DPJ leader Lee Jae-myung. According to Joo’s office, his prediction a week before the November 2024 district court ruling that Lee would be sentenced to a year in prison helped his channel gain 20,000 subscribers almost overnight.

Since launching in April 2024, Joo’s channel has grown to 362,000 subscribers and repositioned him as a conservative political commentator. Unlike many legislators’ channels, which serve primarily as archives of speeches, committee meetings and policy events, Joo’s focuses on commentary and analysis. His office said assistants use data-driven strategies to manage the channel, including analyzing post timing, audience retention and engagement.

Screen grab: rep. Zhu Zhenyu’s YouTube channel/Korea Herald

For most legislators, reaching 100,000 subscribers is a daunting challenge. Among the 296 current MPs, 284 MPs operate YouTube channels in their own names, with an average number of subscribers of approximately 32,100 and a median of only 4,660.

As South Korea approaches local elections in June, online popularity appears to be boosting the electoral ambitions of some lawmakers. At least six of the 25 Silver Button holders are considering or have announced bids for June.

Kim Byung-joo confirmed his intention to run for governor of Gyeonggi Province in early January, while Democratic Rep. Min Hyung-bae is seeking to lead a major city that would merge Gwangju and Jeollanam Province.

Min’s channel has about 78,000 subscribers, making her stand out among lawmakers elected outside the Seoul metropolitan area. Nineteen of the 25 silver play button holders represent the greater Seoul area, which includes Gyeonggi Province and Incheon. Four of them were elected through proportional representation, and only two represented the Busan and Ulsan regions.

On average, legislators in the greater Seoul area have about 54,400 subscribers, while no province outside of the region has an average of more than 10,000 subscribers per legislator, except for Chungcheongnam-do. An official in Min’s office said his YouTube presence is the largest among lawmakers in Gwangju and South Jeolla Province and helps elevate regional issues to the national stage by demonstrating political clout and scalability.

Meanwhile, critics warn that YouTube’s incentives could deepen political divisions. Some lawmakers with large followings often target political opponents to satisfy supporters who prefer confrontational content.

For example, left-leaning Rep. Choi Hyuk-jin played a popular playlist called “Choi Hyuk-jin’s Rants,” which featured heated exchanges with officials and rivals. Councilor Long Huiren’s channel includes a series called “Long Huiren of Carbonated Water,” which highlights her sharp style in parliamentary questions.

This dynamic could constrain politicians, academics say.

“Lawmakers may be hesitant to compromise or moderate their positions for fear that their supporters will turn against them,” said Jong-eun Lee, an assistant professor of political science at Northern Greenville University.

The platform’s competitive logic also tends to reward provocative or performative content. “Material like this travels faster and further than careful policy discussions,” Bisbee said.

This, in turn, could exacerbate polarization.

“Lawmakers’ social media platforms may reinforce existing beliefs by allowing supporters to collect and share affirmative content,” said Eom Ki-hong, a political science professor at Kyungpook National University. “This echo chamber effect ultimately deepens polarization.”

North Greenville University’s Lee added that politically engaged audiences may increasingly “selectively consume media from politicians who align with their own ideologies,” further deepening divisions.