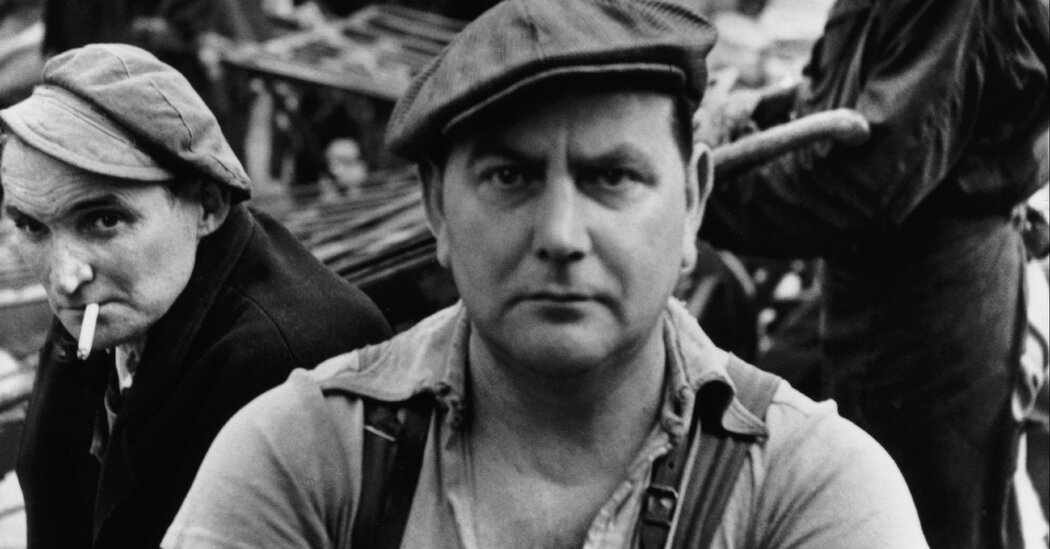

In September 1955, French art publisher Verve launched a large-format book with a cheerful, abstract cover of red, blue, and yellow designed by Catalan artist Joan Miró. It contains 114 photographs taken across the continent, from the rugged west coast of Ireland and the lakes of Switzerland to the steppes of Russia and Ukraine. These photos were taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson. It’s titled “Europeans.”

Apart from some respectable reviews, and despite a parallel American edition, the book did not have much immediate impact – far less than Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment, published three years earlier, which made him the most famous photographer of his era and remains revered by art historians and photojournalists.

Now, more than 70 years after it first appeared, Les Europas finally emerges from the shadows, with the help of a Paris foundation established by the photographer with his second wife, Martine Franck. Escape the crowds of the city’s Marais district and head to the foundation’s basement gallery, where vintage prints and examples of the book are available, as well as copies of elegant new editions.

“‘Europeans’ is so important,” said Clément Chéroux, director of the foundation, who curated the exhibition and the new publication. “Not just because of the photos, which are of course very powerful, but also because of what this project represents.”

Cartier-Bresson experienced a whirlwind tour in the early 1950s, much of it with commissions from publications such as Paris Match, Harper’s Bazaar, and Life and Holiday magazines.

In 1951, he went to rural Italy, then returned to his native France, and then to England. The following year he spent the next year in London photographing the expressionless mourners who gathered in Trafalgar Square for the funeral of King George VI, before traveling to Dublin and the Irish countryside. In 1953, he zipped through Greece, Austria and Germany, capturing the drunken, bleary-eyed party-goers at Hamburg’s New Year celebrations and the deserted streets of Cologne, where buildings destroyed in World War II still loomed eerily above glossy new clothing stores.

“He lived the life of a photojournalist,” Sheru said. “I haven’t traveled abroad for almost a month.”

Europe was changing around him. NATO was founded in 1949, the same year the Council of Europe was established. In 1950, the year Cartier-Bresson began writing Les d’Europeans , French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman announced a road map for what would eventually become the European Union. Five years later, by the time Cartier-Bresson’s book was published, Germany had officially become two independent countries, the Soviet Union had consolidated the Warsaw Pact, and the chill of the Cold War had begun.

Whether or not Cartier-Bresson originally intended to depict the continent through these travels, his publisher Stratis Eleftheriadis (whose given name was Tériade) encouraged him to produce a portrait of the continent. In a 1990 interview for a Greek television documentary, Cartier-Bresson recalled a suitcase “full of photographs” that he had examined with Thériade. “We made the choice together, talked about it and even argued,” Cartier-Bresson said.

Although some images, especially those from France and Spain, appear timeless, The Europeans also depicts Europe during a period of dramatic change. According to a letter in the foundation’s archives, Triad and Cartier-Bresson punned the title of their previous collaboration as “Old World images of a decisive moment.”

The first photo in the book, taken on the outskirts of Athens, deftly balances ancient Greek ruins with gushing chimneys. (Both, the photographer suggests, are monuments to their time.) Later in the sequence, Cartier-Bresson stops on a highway between Genoa and Monte Carlo, Italy, where he and his camera sneak up on a group of workers and photograph the intricate grid of scaffolding beneath a new bridge. The painting not only illustrates Italy’s frantic post-war reconstruction, where the old world surrendered to the new order, but is also a dynamic abstract study of rhythm and energy.

If you ignore the title (printed at the end of the book, although prominently displayed on the gallery wall), it is sometimes difficult to tell which country you are looking at. This in itself is remarkable: a few years ago, millions of people across the continent were at war with each other. Now Cartier-Bresson, who served in the French army and spent nearly three years in a German prison camp, dares to suggest that Europeans are more connected than divided.

Cheroux believes there is a “tension” here – Cartier-Bresson was simultaneously trying to capture the specificity of each country he visited, “but at the same time show that there is a unity,” he said.

For David Campany, creative director, critic and curator at the International Center of Photography in New York, “Europeans” presents something “up in the air” both graphically and politically.

“It’s hard to know what the tone of the book is,” Campany said in a phone interview. “There’s an openness to it. You could put ‘Europeans’ in front of 10 people and they would all react differently.”

Seventy years on, as Europe faces new geopolitical uncertainties and the postwar consensus looks more shaky than ever, these photos are worth looking at, Cheroux said. “They remind us that building a community of countries that have been at war for decades is a dream,” he said. “We should be careful not to destroy this amazing entity that we have created.”

European

Until May 3, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris; henricartierbresson.org.