After nearly three years of volatility, China’s luxury goods market is showing signs of stabilizing. By the fourth quarter of 2025, investment conversations resume, long-suspended projects resume planning, and brands begin to reassess how and where to bet on China again.

In December, Louis Vuitton, Dior, Loyola and Tiffany opened flagship stores in Beijing’s Sanlitun District. Beyond the capital, Chopard traveled north to Harbin, staging an ice culture pop-up that aligned with the city’s winter tourism narrative (and highlighted a growing sensitivity to regional context). Buccellati held its first large-scale brand exhibition in China in Shanghai. The Prince of Goldsmiths: Buccellati rediscovers a classicfrom December 7, 2025 to January 5, 2026, traces the brand’s Italian arts and crafts heritage through historic jewelry and silverware, highlighting the legacy, craftsmanship and evolution of founder Mario Buccellati.

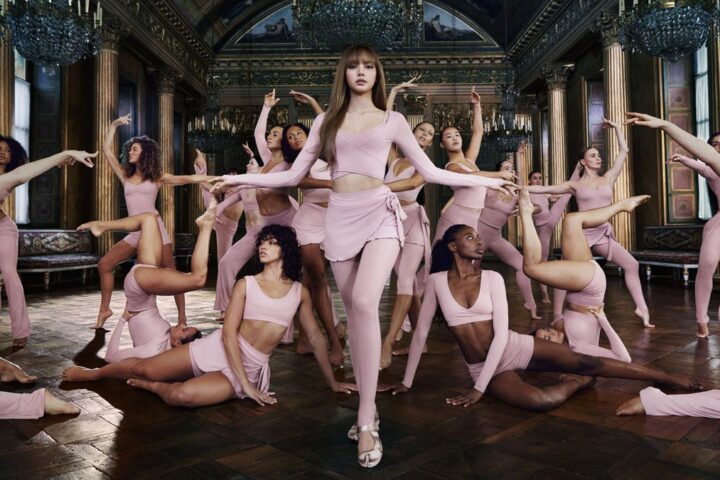

Photo: Courtesy of Chopard

But behind the recovery lies an uncomfortable fact: China is not “back” yet. It has changed shape. The consumers who once drove explosive growth are smaller, sharper and more skeptical. Digital behavior accelerates beyond Western benchmarks. The industry’s most entrenched operating assumptions – from VIC hierarchies to the emotional retail drama – are being structurally challenged.

The question for global luxury goods is no longer whether China will recover, but whether brands are ready to deal with China’s current situation. Winning in China by 2026 will require a fundamentally different strategy.

The end of the old VIC era

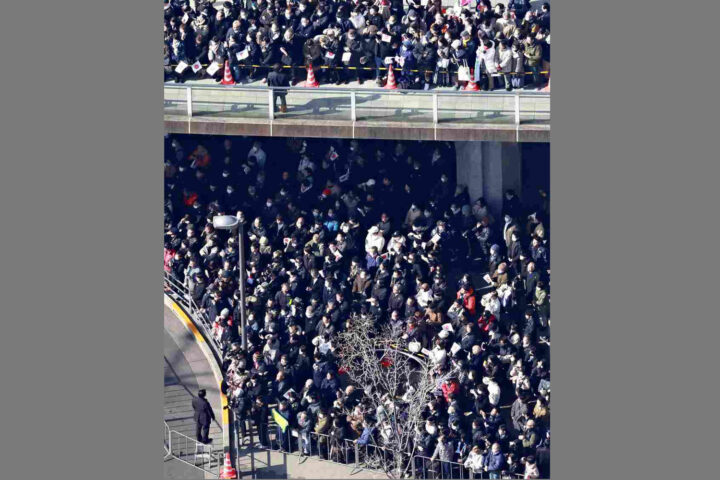

Contrary to expectations for widespread luxury expansion before the COVID-19 outbreak, China’s spending power has been sharply concentrated in Victoria over the past two to three years. As household confidence weakens and asset markets underperform, ordinary consumers retreat and focus on those high-value customers.

Yaoke Research Institute estimates that China currently has about 4.46 million high-net-worth individuals with assets exceeding 10 million yuan (US$1.4 million), a 13% decrease from 2019. Even so, their economic gravity has increased significantly: in 2024, they accounted for 28% of total consumption, contributed three-quarters of the profits of the consumer goods industry, and supported nearly 90% of luxury goods sales.

The implications are obvious. China is no longer an incremental market (where luxury companies can grow by attracting new customers and expanding market share in an unsaturated environment); it is now a zero-sum market, where one brand’s gain is another’s loss. Luxury brands must grow from a shrinking, increasingly rational elite. And the elite is changing from within.

“High-value consumers have become smarter and more reserved,” said Zhou Ting, president of the Yaoke Research Institute. “They are moving from conspicuous consumption to self-directed consumption. Sports, leisure and lifestyle-driven choices are replacing public displays of status.”

This evolution is also reflected on Alibaba’s invitation-only luxury e-commerce platform Tmall Luxury Pavilion, where the classic VIC remains vital but no longer singular. “We are seeing resilience across different consumer groups,” said Anne Liu, the platform’s general manager. “New demographics are emerging, but traditional Victoria is still important. The landscape has become multi-dimensional.”

Liu further added that young consumers in particular are reshaping the logic of luxury participation. Rather than embracing a brand hierarchy, they flow fluidly across categories — legacy brands, niche designers, sport-luxury hybrids and lifestyle brands — guided more by personal aesthetic preferences than a logo. “They are willing to pay a premium, but only if there is an emotional resonance that matches who they are,” she explains.

Yann Bozec, co-founder and managing director of consulting firm YB Stratis and former president of Tapestry Asia Pacific, takes this argument further, challenging the premise of VIC segmentation.

“The problem with VIC is that it’s an industry-defined classification, not a reality for consumers,” he said. “In many brands, the revenue structure no longer justifies it. In the ultra-premium category, everyone should be a VIC by definition. The label loses operational meaning.”