January 29, 2026

Dhaka – There is no shortage of women leaders in Bangladesh, whether in business, government offices or academia. There is a lack of women in electoral politics.

Over the past two decades, women’s influence in public life has expanded steadily and significantly. There are now more girls than boys in secondary education. Maternal and child mortality dropped dramatically. Women’s economic institutions developed through microfinance and the ready-made garment sector, both of which relied primarily on women’s labour. These gains are not accidental but the result of sustained national policies, long-term involvement of non-governmental organizations and deliberate investment in women as economic and social actors.

Women’s representation within the country has also increased. There are 495 upazilas in Bangladesh and today about one-third of all upazila nirbahi police officers are women. Today, women serve at every administrative level: as assistant commissioners, deputy commissioners and senior field officers – roles that a generation ago were overwhelmingly male. This shift is important because it illustrates something crucial: When institutions are rules-based, women advance at scale. But when it comes to party politics and elections, the numbers collapse.

After the deadline for withdrawal of nominations ended last week, women accounted for just over 4% of candidates for general seats in all but two constituencies, while 30 registered parties had nominated no women at all. This is not a pipeline issue but a structural divide: women are increasingly participating in governance and service delivery but are systematically excluded from competing political power. This difference tells us something important: In Bangladesh, women have been professionalized for growth but not politicized for governance.

Although the National Consensus Council proposed requiring political parties to nominate female candidates for 5% of the total seats, most parties failed to implement it. The BNP nominated only 3.5% of female candidates, while Jamaat-e-Islami nominated no female candidates (Prothom Alo, January 22, 2026). Smaller parties initially nominated some women but later withdrew some of them. Former women’s reform commissioners and women’s rights activists have criticized political parties for failing to deliver on promises and limiting women’s political participation. This highlights a broader trend of women being underrepresented in Bangladesh elections, despite prior agreements and advocacy efforts.

Ironically, this country has always been ruled by women at the top of the political hierarchy. This visibility creates an assumption that women’s leadership will gradually trickle down through party structures and electoral channels. But that’s not the case. As I pointed out in an article in the Daily Star titled “The Paradox of Women in Power and the Myth of Soft Leadership”, female leadership at the top does not succeed in dismantling the male structure of party politics but ultimately plays a role within it.

The result is the paradox we now face: in an environment where power remains concentrated, women’s authority is personalized but not institutionalized. Presence has not been a factor in the participation of grassroots and middle-class women in the country.

This makes the current political moment particularly important. The interim government led by Dr. Muhammad Yunus was globally recognized for pioneering microfinance as an avenue for women’s empowerment, and there was a reasonable expectation that women’s political representation would be institutionally guaranteed. But that didn’t happen. Despite its reformist mandate, the interim government did not meaningfully intervene through transitional arrangements, nomination frameworks or implementation mechanisms to protect or expand women’s participation in political decision-making. This failure may now lead to further setbacks in women’s political participation, particularly at a moment when party structures are actively narrowing opportunities.

The exclusion of women from electoral politics is often explained away as cultural, conservatism or a lack of “electability”. But what we are witnessing can be better understood as a political backlash. As women’s social and economic agency expands through education, income, public power, and visibility, their potential political presence becomes harder to ignore. Instead of absorbing this shift, party structures responded with austerity. Women were reassigned to reserved seats. Competitive constituencies were deemed “too risky”. This backlash is not only ideological, but also procedural and strategic.

A recent incident in the National Civic Party (NCP) illustrates this clearly. When senior male leaders chose to ally with the Jamaat-e-Islami, several female leaders left the party in protest. Their exit is not symbolic. It reveals how strategic decisions about ideology and alliances are made without women. Obviously, women’s participation is conditional.

The digital realm continues to reinforce this exclusion. Women who speak out politically face a disproportionate amount of online harassment, moral policing, and character attacks. Political parties interpret this hostility as an electoral liability and use it to justify their reluctance to nominate women. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle: because politics is hostile, women are excluded, and politics remains hostile because women are excluded.

Regional comparisons make diagnosis clearer. In Nepal, constitutional mandates and electoral restructuring have resulted in large-scale women’s representation, with women occupying approximately 41% of local government positions and approximately one-third of parliamentary seats following the introduction of a quota system. These outcomes did not emerge organically but were the result of institutional coercion that reshaped party behavior. Bangladesh’s reliance on voluntary reforms has brought symbolism, not power.

The comparison is telling. In the civil service, there are rules for entry and promotion, and there are now a large number of women in leadership positions. In politics, where women’s participation depends on discretion, loyalty networks and informal negotiations, women remain marginalized. This is the result of institutional design, not a failure of ability, ambition or preparation.

The expanding economic space for women is clearly a boon for Bangladesh. As of December 2024, more than 40 million people had accounts with microfinance institutions, 90% of whom were women. At the same time, the female workforce underpins the export-oriented ready-made garment industry, underpinning the country’s economic growth. These gains were achieved through decades of negotiations between states, NGOs, civil society and women themselves to normalize women’s visibility, mobility and authority in public life.

But the backlash we’re seeing now could stop that trajectory at the political threshold. If women’s negotiating space continues to be limited to economic participation and bureaucratic services without extending to suffrage, Bangladesh risks institutionalizing the caps it once claimed to dismantle. Curbing this backlash is not just about symbolism or fairness, but also about ensuring that the nation’s investment curve in women doesn’t stall on the most important question: who will govern.

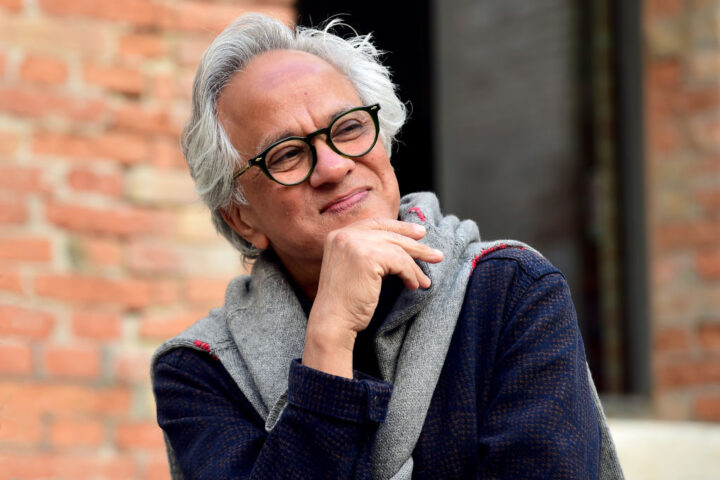

Tasmiah T Rahman works at Innovision Consulting and is pursuing a joint PhD program on the political economy of development at SOAS, University of London, and BRAC University, UK.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.