China-Venezuela relations have long been close, and both sides have advocated them at major national events. There is little substance behind these passionate declarations.

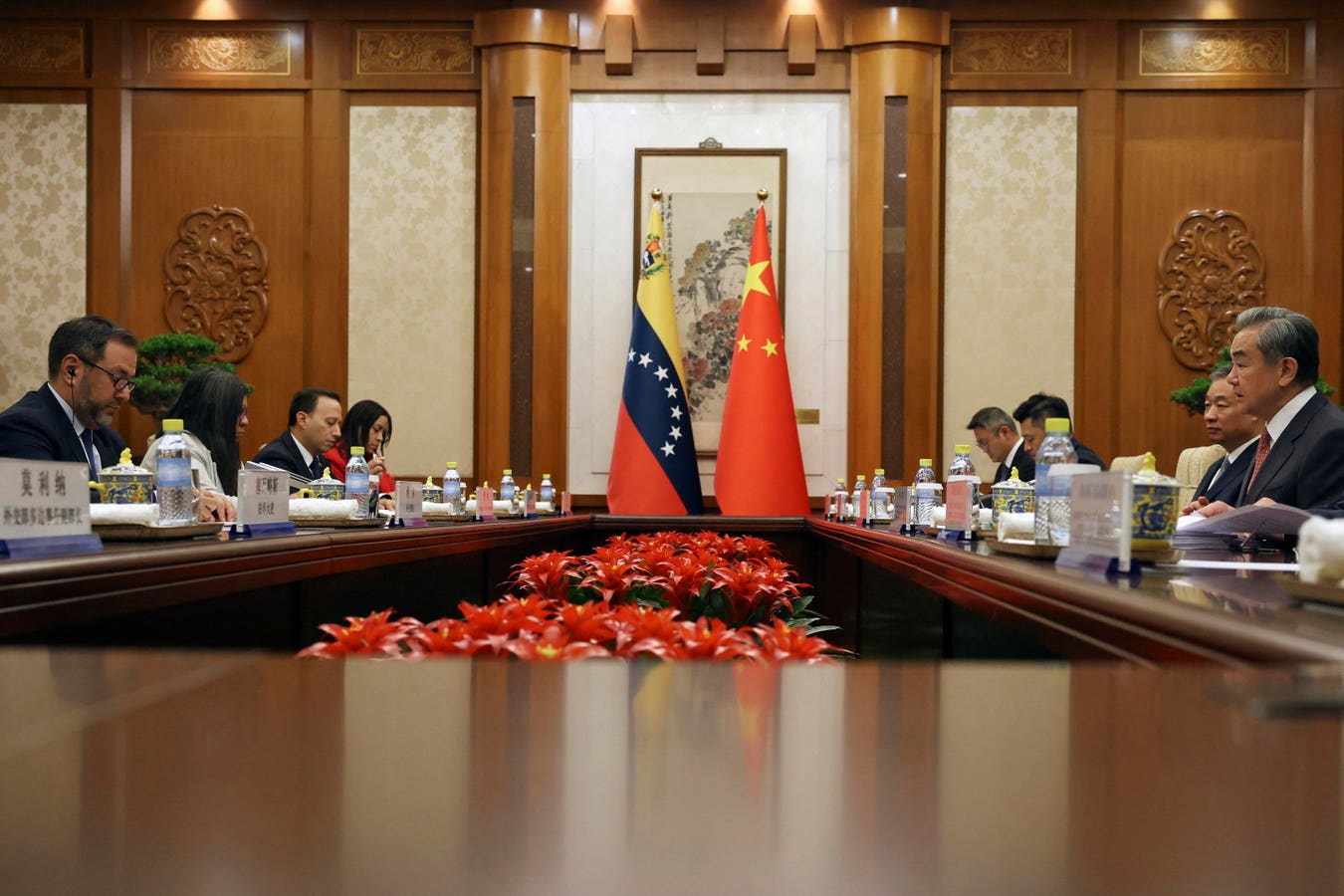

POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Washington has unsurprisingly drawn condemnation from Beijing since tensions between the United States and Venezuela have escalated over a U.S. raid that captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Many Chinese media expressed shock and disgust at the United States’ disregard for international norms and basic principles of sovereignty.

Amid these new headlines, some observers speculate that Beijing may step in to stabilize Caracas and reshape global oil markets. Fear of Chinese influence in the Western Hemisphere undoubtedly motivates the Trump administration. However, the reality is far less dramatic, and we should not hold our breath waiting for China’s vocal condemnation to turn into more concrete support.

Venezuelan oil: too heavy, too niche

Although Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves (a staggering 30 billion-plus barrels, or about 17% of the global total), only a fraction of them are easily accessible. Much of the country’s supply is extra heavy and sour, requiring specialized diluents and refinery configurations, much of which is located in the United States. Tim Gould, chief energy economist at the International Energy Agency, described Venezuela’s oil infrastructure as “shabby” and “obsolete.” Venezuela’s oil infrastructure severely limits the country’s current ability to bring oil to market and will likely require significant investment to have any meaningful impact on energy markets.

Sluggish production in Venezuela is another limiting factor. Since 2013, Venezuela’s oil production has fallen from 2.5 billion barrels per day to less than 1 million barrels per day by 2025. Chronic mismanagement, corruption and U.S. sanctions have left infrastructure in decline and skilled labor scarce. The wells in Caracas need not a simple restart, but a full re-drilling, and Venezuela’s lack of operational resilience prevents it from impacting global markets in the short term.

As a sign of concrete commitment, China’s military exports to Venezuela have dried up.

© 2025 Bloomberg Financial Limited

China’s patience is limited

China’s relationship with Caracas is increasingly shaped by caution and risk management rather than deep strategic commitment. Venezuela continues to struggle economically and politically, making it an unreliable partner.

China remains Venezuela’s largest oil customer, with Venezuela importing about 90% of its oil. While the numbers look impressive on paper, Venezuelan crude accounts for only a small fraction of China’s imports, less than 5%, according to oil analytics firm Vortex, and decades of mismanagement in Caracas have eroded Beijing’s confidence. Even before the latest geopolitical shock, China had already withdrawn from its South American partners. Beijing’s massive “loan-for-oil” arrangements, once central to its engagement, slowed sharply after the mid-2010s and effectively ended in 2016 as falling oil prices, U.S. sanctions and a sharp decline in Venezuelan production made debt repayments increasingly fragile. China’s banks and state-owned oil companies are wary of further extending risks to partners that are struggling to meet even existing obligations. Indeed, the waste of some $65 billion in loans and a rocky relationship with the corrupt Chavista governance project under Nicolás Maduro have left a bad taste in the mouth.

Shortly after the Jan. 3 attack, China’s top financial regulator asked its policy banks and other major lenders to report on the risks of their lending to Venezuela, reflecting Beijing’s concern about financial risks rather than confidence in Caracas’s economic or political stability. This shaky trust is also reflected in the decline in military trade. According to SIPRI, China has not shipped new military equipment to Venezuela for more than three years — a clear sign that its strategic commitment is waning. Formal arms transfers have largely dried up, and in addition to arms sales, the inefficiency of Chinese radar systems during the January 3 attacks further undermined Beijing’s incentives to expand military ties.

Empty talk, not market impact

While recent statements from Caracas and Beijing have grabbed headlines, suggesting the former could reshape energy markets, the structural reality tells a different story: low-quality oil, crumbling infrastructure and entrenched political dysfunction mean global supplies remain largely unaffected. For now, China’s rhetoric is largely symbolic, aiming to exert influence without investing capital or risk.

While Beijing continues to spout high rhetoric, its eroding trust in Venezuela, coupled with the latter’s lack of operational flexibility, suggests that the likelihood of any real action from Beijing remains slim.