You can’t see every work on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and you probably shouldn’t even try to, either—unless you intend to spend days on end at this hallowed New York institution, methodically going wing by wing, gallery by gallery. We wouldn’t blame you for doing just that; the Met remains not just one of the top museums in the United States but one of the greatest encyclopedic institutions in the world. But the truth is that most of us are short on time, and that makes for some hard decisions.

Perhaps you are lucky enough to have three hours at the Met. Where to first? The remarkable Egyptian wing, where the Temple of Dendur acts as a destination for tourists and Met habitués alike? The sprawling European paintings wing, where one can find masterworks by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Rubens, and the like? The newly redone Rockefeller Wing, filled with treasures from Africa, Oceania, and the ancient Americas? And that’s to say nothing of the special exhibitions!

Let us guide you. Below are 100 works to see at the Met, from relics of fallen civilizations to iconic artistic documents of our time. These pieces traverse multiple millennia and many disparate countries and are arranged below chronologically to encourage cross-cultural viewing.

These works are grouped loosely below by wing, but they are not ordered by importance or quality—all are great, and anyway, ranking the Met’s many artistic jewels would be too punishing a task. For plotting your own trip, we recommend consulting the Met’s website, where you may make some discoveries of your own.

A note on methodology: The Met, like many other U.S. institutions right now, has been slowly changing what’s on view, in part to accommodate collection rehangs and in part to respond to repatriation requests. (And that’s to say nothing of loans to other institutions’ special exhibitions, which happen periodically.) Also, the Met is typically remodeling at least one wing at any given moment, which means that certain works that appear here may not currently be on view. We’ll update this list periodically to note when an object is off view but will soon return.

Mastaba Tomb of Perneb, ca. 2381–2323 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Most who visit the Met’s bountiful Egyptian galleries rush toward the Temple of Dendur (more on that in a bit), even though another walk-in ancient structure greets them in this wing. That structure, which once housed the body of a priest and prince named Perneb, has been transported to the Met’s galleries in its ruined form. Visitors can enter this structure, once part of a rectangular tomb known as a mastaba, and view a reconstructed serdab, or statue chamber, where painted reliefs emphasize Perneb’s connection to the sun god Ra, whom ancient Egyptians worshiped as a life-force. The obelisks that once accompanied this mastaba, dating to the Fifth Dynasty, are no longer here, but even without them the tomb retains its majesty.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

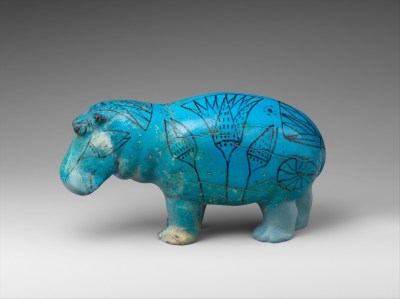

Hippopotamus (“William”), ca. 1961–1878 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art To contemporary eyes, this sculpture of a hippo is irresistibly cute—so adorable, in fact, that the Met now vends plush replicas of it in its gift shop. But in ancient Egypt, animals such as this one symbolized violent, unruly nature. The desire to tame Egypt’s fauna may have been what led the treasurer Senbi II to be interred with this sculpture, which was made using an earthenware material known as faience. Glazed in blue and painted with lotuses, this hippopotamus has retained its beauty for more than 4,000 years, acting now as one of the main attractions not just in the ancient Egyptian galleries but in all of the Met. Most who come to see it know it by its nickname, William, a cutesy moniker given to this piece by a British humor magazine during the 1930s.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Seated Statue of Hatshepsut, 1479–1458 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh who crowned herself ruler of ancient Egypt, continues to fascinate us because of the way she flouted the gender roles of her day. (Met nerds—like yours truly—look back fondly on a 2005 blockbuster show about her that was staged at this museum.) The sculptures that depicted her aided in that subversion, for many seemed to represent a man rather than a woman. That makes this sculpture, crafted from limestone and initially painted in blue, an anomaly, since it clearly depicts a female sitter, with her breasts left visible to the viewer. Here, Hatshepsut is shown seated and wearing a kiltlike garment. She appears ready to receive the offerings that would have been placed at her feet.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Fragment of a Queen’s Face, ca. 1390–1336 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Few artworks in the Met’s collection contain quite so much mystery—and quite so much beauty—as this 3,400-year-old sculpted half of a woman’s face. The identity of the woman represented here in jasper (might it be Queen Nefertiti herself?) has been lost to history, as has the body to which this chin and neck were once appended. Never mind any of that. The lips are pressed firmly into a knowing expression whose intrigue still can be felt. What remains can stand on its own, showing that the riddles of the past are sometimes best left unraveled.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Temple of Dendur, ca. 10 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Were one to make the painful decision to view just one work at the Met to the exclusion of all the others, most would probably opt for the Temple of Dendur, a reconstructed ancient Egyptian structure replete with fountains, sculptures, reliefs, and more. Lavishly installed in an airy room of its own, the sandstone temple dates to the Roman period and was dedicated to Isis, a goddess said to help usher the dead into the afterlife. Alongside sculpted images of lotus flowers and a range of hieroglyphics, there are images of Caesar Augustus of Rome, who then ruled Egypt. In 1965 Egypt gifted the Temple of Dendur to the United States, which had contributed $16 million to a UNESCO fund to save threatened Egyptian antiquities, and it went on view at the Met in 1978. Few institutions other than the Met could have received such a temple, let alone housed it for generations to come.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Portrait of the Boy Eutyches, 100–150 CE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This painted portrait is exhibited in the Met’s galleries for ancient Egyptian art, but the work attests to a rich cross-cultural pollination that exceeds the remit of just one wing. Because the work was produced during a period when Egypt was under Roman rule, it was painted in a distinctly Roman style. But the painting would have been placed on top of a mummy’s face—something that Romans wouldn’t have done with such an image. Executed using the encaustic technique, which involves combining pigment with hot wax, the work is one of around 1,000 extant paintings known as Fayum portraits, named so because many of them were found in Egypt’s Faiyum Basin.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Marble Seated Harp Player, 2800–2700 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Multiple millennia ago, residents of the Cyclades islands in the Aegean Sea, off the coast of what is now Greece, set art on a new course with their spare sculptures of people. In this one, a seated person is shown plucking a lyrelike instrument known as a kithara. Though certain parts are detailed—note this figure’s tiny toes, each marked out with precision—the sculpture is highly stylized, with the kithara appearing to merge with its player’s shoulder. The smoothness of the marble and the elegant minimalism of its forms, alternatively angular or arced, paved the way for future Greek artists, who would gradually move toward increased naturalism—and for modern and contemporary artists, who drew on the simplicity of Cycladic art.

Where to find it: Greek and Roman Galleries

Terracotta Stirrup Jar with Octopus, ca. 1200–1100 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The many well-preserved statues of men, women, and children are the main attractions of the Greek and Roman galleries, but the pottery on view in vitrines around these rooms offers charms of its own. One such delightful vessel is this Mycenaean jar fashioned from terracotta. It once served a practical purpose—its owner would have used it to tote liquids around—but it now exists mainly to be admired for the stylized octopus painted across its surface, its tentacles splayed out amid swimming fish. The minimalism of ancient vessels like this one provided fodder for modernists looking to learn from the past, centuries later.

Where to find it: Greek and Roman Galleries

Bronze Statuette of a Veiled and Masked Dancer, 3rd–2nd century BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art What this statuette lacks in size it makes up for in beauty. It stands just 8½ inches tall and dates to the Hellenistic period, a time when ancient Greek sculptors worked tirelessly to achieve a sense of naturalism that their medium previously lacked. That explains the sheer drape that ensconces this mysterious dancer, who moves her body beneath fabric that catches on one foot to reveal a slipper. The detail on that drape—its rippling folds in some places, its tautness in others—remains potent to this day.

Where to find it: Greek and Roman Galleries

Cubiculum (Bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Italian commune of Boscoreale was trapped beneath volcanic ash during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, preserving the frescoes found in ancient Roman rooms such as this one reconstructed at the Met. Spread across the walls are paintings executed with an astonishing degree of illusionism. Juicy fruits, rows of columns, cracked maroon walls, craggy hills, and stately statues all appear here, rendered with such detail that these paintings appear to act as windows onto the world. Only the wealthy could afford such vistas, however; this bedroom once belonged to a luxury villa for the aristocracy. The good news is that one need only pay the Met’s admission fee to enjoy these paintings today.

Where to find it: Greek and Roman Galleries

Marble Statue of an Old Woman, ca. 14–68 CE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This ancient Roman statue is technically a copy of a Greek one belonging to the Hellenistic period, when sculptors found new and creative ways of mimicking the human form with a greater degree of naturalism. Attention has been paid here to the folds of the old woman’s loose dress—a typically Hellenistic flourish that rhymes nicely with her aged skin, which sags in places as she marches onward. Given her ivy wreath, she is probably walking toward a party in honor of Dionysos, the god of wine, and indeed, the original Greek work may have once figured in a sanctuary in his name.

Where to find it: Greek and Roman Galleries

Statue of Gudea, ca. 2090 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art At less than 18 inches tall, this squat sculpture exudes a sense of authority, a testament to the skill of its Neo-Sumerian craftsperson. The sculpture depicts the ruler Gudea, who, following the fall of the Akkadian Empire, helped turn Lagash, in what is now Iraq, into a prosperous city-state, with many temples of note. Carved from diorite, a tough rock that few knew how to sculpt at the time, the piece contains a Sumerian inscription that boasts of Gudea’s ability to commission sites of worship. His steely gaze, his taut posture, and his clasped hands project austerity and power more than four millennia on.

Where to find it: Egyptian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Lamassu, ca. 883–859 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Met’s wonderful galleries for ancient West Asian and Cypriot art are currently closed while they undergo renovation, which is too bad: Their star, this winged bull known as a lamassu, ranks among the most awe-inspiring works to be found anywhere in a museum that’s chock-full of them. Before coming to the Met via John D. Rockefeller, this lamassu was surrounded by others like it as part of an enormous mud-brick wall protecting the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, king of the Assyrian empire, which included portions of modern-day Iran and Egypt. Even in isolation, however, this eight-ton limestone sculpture holds its own, in part thanks to its strangeness. Notably, it has five legs to hold it upright instead of the four one expects from most earthly animals.

Where to find it: Ancient West Asian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Plate with a Hunting Scene from the Tale of Bahram Gur and Azadeh, ca. 5th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Most people skip the displays that house small works between the second-floor galleries for European painting and Asian art. It’s their loss, for the vitrines here hold gems such as this silver plate, which the Met notes bears one of the earliest depictions of the Sasanian king Bahram V being challenged to shoot gazelles by his hunting companion, the harpist Azadeh. According to Sasanian lore, Azadeh intentionally gave Bahram the impossible task of switching two gazelles’ genders, but the king somehow managed to pull it off. His feat is immortalized here via a busy composition in which arrows fly as gazelles tumble beneath his horse’s feet. Bahram looks on stoically, seemingly unfazed by the difficulty of his task.

Where to find it: The Great Hall

Marble Portrait Bust of a Woman with a Scroll, late 4th century–early 5th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art You’ll have to hop on the uptown A train to see most of the Met’s Byzantine and medieval treasures, which are housed largely at the Cloisters, the dedicated annex of that curatorial department. But for those not willing to make the journey—which is long, yes, but worth it—there are still some great works to be had at the Met’s Fifth Avenue base, including this bust produced in Constantinople. It depicts a woman holding a scroll, and in the portrait one can sense an intense psychology behind her carefully crafted eyes.

Where to find it: Late Roman and Early Byzantine Galleries

Fragment of a Floor Mosaic with a Personification of Ktisis, 500–550

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Not so long ago, this fragment of a larger mosaic was itself composed of two fragments: The Met acquired its pieces, one for each figure represented, in the 1990s, then brought them together after studying pictures from a dealer who had held them prior to their separation. Today those fragments seamlessly combine to illustrate the human embodiment of Ktisis, a concept that denotes “the act of generous donation or foundation,” per the Met. Whereas this mosaic from the Byzantine era was once the source of fascination for its tesserae, which are laid in an expressive way that highlights folds on Ktisis’s neck and shadows under her eyes, it now provides scholarly fodder for historians researching the contributions that Africa made to the development of art in the ancient Mediterranean, since this mosaic may have been found in North Africa.

Where to find it: Late Roman and Early Byzantine Galleries

Seated Hollow Figure with Helmet, 1200–800 BCE

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The exact purpose of this sculpture, one of the many artworks of its kind known as Olmec “babies,” remains unknown: experts have speculated that it could have honored the loss of a child, or perhaps functioned as a depiction of an adult shown in a younger form. Whatever the case, this genderless infant bespeaks the centrality of babies to Olmec culture, which viewed them as being intimately tied to the natural world. Recovered from the Las Bocas site in what is now the Mexican state of Puebla, the sculpture is crafted from ceramic, coated in white slip, and painted with red highlights. Its flabby stomach evinces a level of naturalism that is surprising even to contemporary eyes.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Tunic, 650–1000

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2025, when the Met unveiled its renovated and rehung Michael C. Rockefeller Wing for art of the ancient Americas, Africa, and Oceania, textiles emerged as a new focus, and this tunic produced by the Wari people emerged as a gem. Other tunics produced by the Wari, who lived in what is now Peru, likewise feature animals abstracted nearly beyond recognition. But many of those tunics have gridlike compositions, while this one, with its cascade of zigzags, circles, and hash marks, feels liberated from such a rigid logic. Were it not displayed alongside so many other objects from long ago, it could easily be mistaken for a piece of contemporary art.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Ùhúnmwèlaò (Head of an Óbà), 16th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Though this work might seem like a portrait of an oba, or a ruler of the Kingdom of Benin, it was not meant to be a precise likeness. Working in bronze, its maker instead sought to portray such a king at the height of his power, projecting authority and stateliness. Sculpted heads such as this one were particularly valuable in Benin, and they have been collected widely by museums—though there is now a push to start sending them back home. This head, along with many other objects collectively known as the Benin Bronzes, was stolen in 1897 when British troops pillaged Benin. The Met has returned just a few of its Benin Bronzes; this one remains in New York.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Ìgbèsànmwà artists, Pendant Mask of Ìyọ́bà Idià, 16th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art An iconic work of the Rockefeller Wing, this pendant mask may have depicted Idià, the mother of Esigie, a ruler of the Kingdom of Benin during the 16th century. Esigie may have worn this ivory portrait of Idia, whose head is bordered at the bottom by bearded figures sculpted from coral, identified by the Met as Portuguese men who traded with the kingdom. (Mudfish, meanwhile, line the top of her head, forming a tiara of sorts.) The mask was plundered by British soldiers in 1897 along with a group of objects popularly known as the Benin Bronzes. In recent years, the Met has shown a willingness to repatriate some of the bronzes in its collection, sending a few home to Nigeria.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Dan artist, Wunkirmian or Wakemia Feasting Spoon, 19th to mid-20th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This spoon would have been used at feasts held by the Dan people in locales such as Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. Anthropomorphized with a pair of legs jutting out of its bottom, the spoon represents a female figure, its concave upper portion standing in for a head. The abstracted human bodies of Dan spoons have intrigued legions of sculptors over the past century, from Alberto Giacometti to Simone Leigh, whose work for the U.S. Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale featured sculptures alluding to utensils similar to this one.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Yombe-Kongo artist and nganga, Mangaaka Power Figure, ca. 1880–1900

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This power figure is known as a nkisi nkondi, a type of statuette produced by the Kongo people in the Congo region of Central Africa. The statuettes often contain nail-like pieces of metal driven through them and are crafted with the aim of warding off evil. For that reason, nkisi nkondi were thought to be vested with mythical power, able to protect those who possessed them. This one, a star of the Rockefeller Wing, features at its core an empty center that may have once been filled with medicinal matter, according to the Met.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Yoruba bead artist, Adéńlá, late 19th–early 20th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Among the great joys of the Met’s 2025 rehang of its Rockefeller Wing was a new spotlight on Yoruba bead art, whose lushly colored glass elements combine to create astonishing abstract patterns and beguiling faces. The faces seen on this crown each have protruding eyes and thin smiles; the bands of red coloration punctuating their blue cheeks evince what is known as ojú-ọnà, or a kind of design sense unique to the Yoruba people of modern-day Nigeria. Though it’s hard today to imagine donning an object so beautiful, this crown once sat upon a Yoruba leader’s head and would have held herbal medicines provided by a priest.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

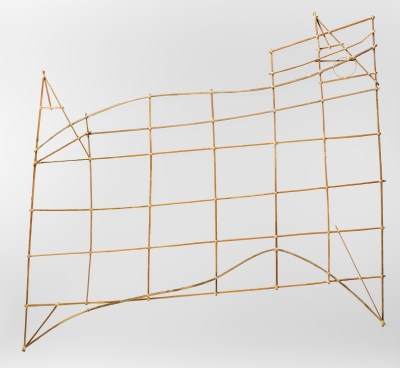

Marshall Island artist, Rebbilib, 19th–early 20th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Though it looks like some sort of proto-Minimalist sculpture, this object once functioned as a navigational chart for Marshallese people traversing the Pacific Ocean. How might it have been readable as a map? One possibility is that the gridded area in the center, formed form the midribs of coconut fronds tied together with fiber, may have referred to tidal phenomena in the ocean, and that its corners, which protrude outward, may have indicated the locations of islands. For the Marshall Islanders, this map could also have served as a teaching aid. For most contemporary viewers, however, it is virtually illegible—and all the more fascinating because of it.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Headdress Effigy, late 19th–early 20th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Hard to believe, because it measures 15 feet tall, but this object once would have been worn atop one’s head during harvest dances conducted by the Chachet Baining people in what is now Papua New Guinea. (Mercifully, it’s made largely out of barkcloth, a relatively light material.) Known as a hareiga, this type of headdress is no longer in use by the Chachet Baining, and its exact purpose remains unknown. Still, it regularly lures admirers to the Rockefeller Wing, where for many years it was tilted menacingly over viewers. More recently, it has been encased in glass, to protect it from light damage.

Where to find it: Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Head of a Buddha, 5th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The quietest corners of the Asian art wing—an expansive group of galleries where there tends to be less foot traffic than elsewhere—provide some of this museum’s great thrills. Here you can observe as cultures press up against one another, resulting in hybrid styles such as the one seen in this head of a Buddha, which may have come from Hadda, a Greco-Buddhist archaeological site in what is now Afghanistan. The almond-shaped eyes and long, thin eyebrows were stylistic touches in vogue at the time in India, a country located far from Afghanistan. That such flourishes traveled so many miles beyond their homeland testifies to a robust cross-national dialogue.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Standing Ganesha, 7th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Not so long before this sculpture was produced, Ganesha, the Hindu deity associated with removing obstacles, was often portrayed with an idealized body. But during the Pre-Angkor period, when this sculpture was made, artists started to depict Ganesha more naturalistically, which is why this version of the god with a human’s body and an elephant’s head remains so remarkable. Note the attention paid to his stomach, which bulges beneath a garment known as a sampot. Its unknown sculptor seems to be saying that Ganesha’s body is subject to the same pressures of aging and time as the rest of us—even if he is a divine being.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Chamunda, the Horrific Destroyer of Evil, 10th–11th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Were one to pick the scariest work on view at the Met, this sandstone sculpture of Chamunda, a Hindu goddess associated with vanquishing evil, would be a strong contender. With her sharp teeth and her tiara made from tiny skulls, this ancient Indian sculpture projects a fearsome presence—and it would have only been more so in its original state, before some of its sculpted appendages were lost to time. According to the Met, this Chamunda once had 12 more arms, some of which held weapons.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja), 11th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Between the 9th and 13th centuries, during the Chola dynasty in southern India, bronze sculpture underwent a mini-renaissance, spurring artisans to represent Hindu gods in ways that appeared more naturalistic than they had before. The Shiva Nataraja, a depiction of Shiva dancing with his hair flying out from his head, became one of the most popular representations of that sort to emerge from this era. Surrounded by a ring of fire known as a prabhamandala, this Shiva appears to persistently twirl, symbolizing the constant churn of time.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Buddha of Medicine Bhaishajyaguru (Yaoshi fo), ca. 1319

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art There may be no larger painting regularly on view at the Met than this Yuan dynasty masterpiece, which, at 24 feet tall and 49 feet wide, acts as the central artwork around which all other pieces orbit in the Chinese art galleries. It depicts at its center Bhaishajyaguru (informally known as the “Medicine Buddha”), flanked by the bodhisattvas Candraprabha and Suryaprabha, as well as a range of other figures assembled to bear witness to Bhaishajyaguru’s healing powers. Art historians have been unable to definitively nail down who painted this work, which would have looked even more formidable in its original setting at the Lower Guangsheng Temple in the Shanxi province. But it may have been done by Zhu Haogu, who was known for expansive murals like this one featuring Buddhas surrounded by clusters of bodhisattvas.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Fang Congyi, Cloudy Mountains, ca. 1360–70

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The leftmost portion of this Chinese scroll features a blank expanse with just the faintest hint of mountain peaks in the distance. It’s a jarringly abstract image for a work that predates the modern era by around six centuries. But then again, Fang Congyi, the Daoist priest who painted this scroll, was interested in the intensity of human mortality, a topic that isn’t always so easy to visualize. He was comfortable working in a figurative mode, too, of course: Using a brush loaded with ink, he here expressively rendered a temple, trees, and rock formations. At the time he made this work, the viewer would have started at that temple and gradually unrolled this scroll, viewing the piece from right to left. As one’s eye journeyed toward the mountains, one would notice a shift in Fang’s brushwork, which grows gradually looser and more unstable. In the end, his contemporaries were left with nothing much to see at all—a reminder of their own limits in the face of sublime nature.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Ten Elements for the East Window of an Architectural Ensemble from a Jain Meeting Hall, ca. 1575–1600

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art During the Mughal period, India’s Gujarat state became the capital for an ornate kind of woodcarving that was used widely for sculptures and temple architecture. Remarkably, the Met is home to a particularly sizable example of that woodcarving: an entire dome, plus some accompanying balconies and supports, from a temple for followers of Jainism in Patan. Nearly every part of the teakwood surface is covered in images of deities, lotus flowers, and more. Dramatically lit and mounted on the museum’s ceiling, this portion of the temple can be viewed from an elevated area of the Asian art wing.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Astor Chinese Garden Court, in the style of the 17th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art In 1979 the Met engineered the first cultural agreement with China since the Communist Party rose to power, a deal that resulted in the making of this garden court. No, it is not an actual Ming Dynasty garden court, but its benefactor, Brooke Astor, conceived it as a faithful facsimile of one, complete with real Taihu rocks (eroded chunks of limestone studied by Chinese scholars), live bamboo, and a circular design seen widely in Chinese architecture of the era. Finished in 1981, the garden was considered a diplomatic feat during its day. Today it remains impressive both as a technical marvel and as a haven for those seeking a respite from the Met’s busiest galleries.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

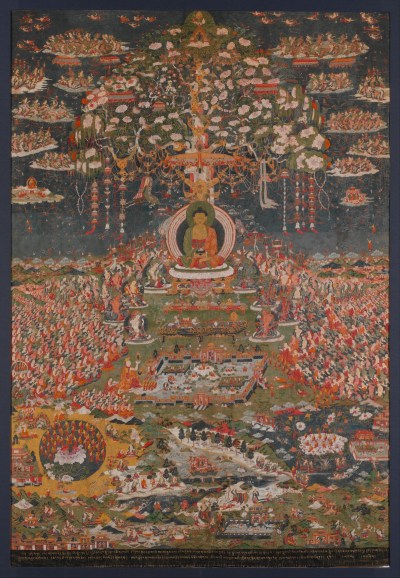

Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Pure Land (Sukhavati), ca. 1700

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Though it stands less than five feet all, this painting conveys an impressive sense of scale, with legions of tiny people assembled to learn the teachings of Amitabha, the Buddha of infinite life in Tibetan Buddhism. Known as a thangka, this work was painted on cloth in vibrant blues and reds. It’s loaded so densely with detail that one may miss some of its most minute particularities, such as the ducks that swim in a river alongside the men who’ve waded into it.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Ogata Kōrin, Rough Waves, ca. 1704–9

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Ogata Kōrin renders the crashing surf of an unsettled ocean with elegance, outlining the crests of his waves in thin washes of ink. Such grace may seem at odds with his subject matter: Why represent nature’s unforgiving churn as though it were a beautiful thing to behold? Because that clash between opulence and terror makes this folding screen a star of the Met’s galleries for Japanese art.

Where to find it: Asian Galleries

Not currently on view.

Helmet (Zukinnari Kabuto), 16th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Art took an extravagant turn in 16th-century Japan during the Momoyama period, when the powerful daimyo (feudal lords) began adorning the spaces they inhabited with lush folding screens marked by their use of gold accents. Gold was also used prominently for this helmet, which was lacquered using a technique known as tataki-nuri, which yields an uneven texture that causes the gold to look like fabric. Attached to the helmet is a spray of licking flames and a representation of the Buddhist god Acana, who here brandishes a sword. To wear the helmet must have felt empowering; to look at it is glorious.

Where to find it: Arms and Armor Galleries

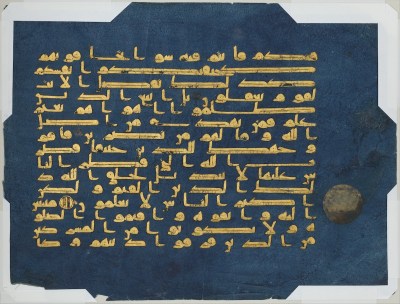

Folio from the Blue Qur’an, second half 9th century–mid-10th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The 100 or so remaining folios of the Blue Qur’an, one of the most famous versions of the core text of Islam, have been dispersed across the world, making the one from which this page is taken a valuable cornerstone of the Met’s Islamic art holdings. Produced in Tunisia, this Qur’an featured parchment pages memorably dyed with indigo. Onto those deep-blue backgrounds, its maker spelled out a portion of the 30th sura—a verse that describes the Byzantine–Sasanian War—in Kufic calligraphy rendered in gold and silver. The work retains its shine more than 10 centuries on.

Where to find it: Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Galleries

Not currently on view.

Bowl with Arabic Inscription, 10th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Samanid pottery is prized today for the clarity of the forms painted by its makers, who were able to work with such precision because they coated their red earthenware in slip combined with pigment. The white slip utilized here lends this bowl a minimalism that feels jarringly contemporary. Adding to its visual impact is the calligraphy that rings its border, which, unlike the text of the Blue Qur’an folio, is so stylized that it verges on illegibility, the letters’ curves and points rendered in such a manner that they nearly become abstract. Those letters spell out words to the wise: “Planning before work protects you from regret; prosperity and peace.”

Where to find it: Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Galleries

Not currently on view.

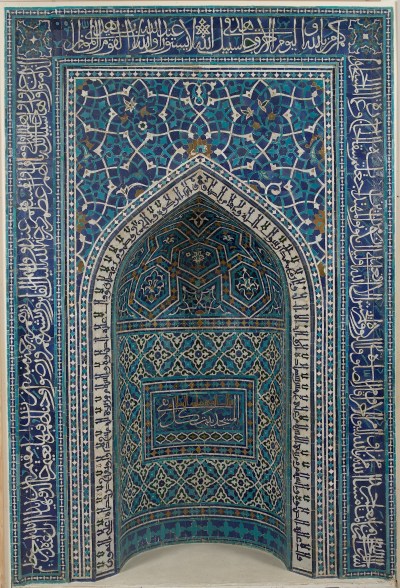

Mihrab, 1354–55

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The words of the Prophet Muhammad nearly melt into abstraction in this glorious prayer niche known as a mihrab, which was once sited in a madrasa—an Islamic school—in the Iranian city of Isfahan. Surrounding that text, which is written in Kufic script on the white border lining the mihrab’s inner arch, are flowers that are themselves encased in another band of text quoting the Qur’an. Those letters loop and curve in the same way as the rosettes seen amid the indigo tilework all around them, hypnotizing the eye while also offering much for followers of Islam to meditate on. Its maker clearly drew no division between holy teachings and the world they were meant to shape.

Where to find it: Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Galleries

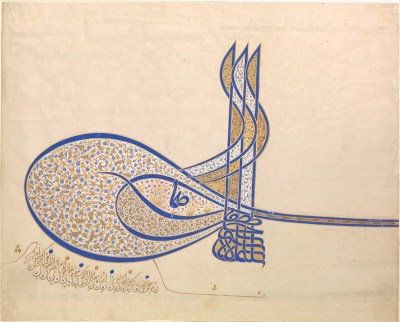

Tughra of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, ca. 1555–1560

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Islamic art galleries have many examples of texts filled with Arabic cursive that curlicues and coils. But on the basis of sheer elegance, this tughra—or royal insignia—for Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent is the high-water mark here, its diwani cursive offering up letters that loop back before dramatically jutting across the page. This kind of cursive was hard to read and even harder to copy, reinforcing the idea that Suleiman was unequaled. The smaller letters at the bottom spell out an inscription that underlines the notion: “Sultan Süleyman Khan, the son of Sultan Selim Khan, may his reign endure forever.”

Where to find it: Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Galleries

Attributed to Bhawani Das, Great Indian Fruit Bat, ca. 1777–82

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Bhawani Das, the artist who likely made this work, trained in Mughal painting before creating images for the Impey Album, a group of paintings commissioned by Elijah and Mary Impey, British-born patrons who wanted to take stock of their menagerie in Calcutta. If Das really did make this painting, his training would explain its unusual attention to detail, with each piece of fur clearly delineated. But it’s the bat’s eyes that are the center of attention here. Represented with a certain glassiness that causes them to glint, the eyes seem to convey the kinds of emotions typically afforded only to human subjects.

Where to find it: Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia Galleries

Virgin and Child in Majesty, ca. 1175–1200

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This wood sculpture, of a type known as a Throne of Wisdom, depicts the Christ Child seated in the Virgin Mary’s lap—but despite this Christ having a juvenile’s body, his face looks unusually adult, perhaps to denote the sagacity he had already displayed at such a young age. Carved in medieval France, it is today prized for its unusual stylings, with the folds of the Virgin Mary’s dress represented here by rippling wood ridges. Once owned by none other than the prominent financier J. Pierpont Morgan, it’s now a star of the medieval art wing, where it even manages to outshine the enormous choir screen at the galleries’ center.

Where to find it: Medieval Galleries

Arm Reliquary, 13th century

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art According to popular lore, contained within this metal sculpture of an arm are objects that once touched an actual arm—the arm of a saint, that is. You can’t see those objects today, of course, because they are stowed away inside this reliquary, which is thought to have been produced somewhere in medieval France. You couldn’t have seen them back then, either, when reliquaries like this one would have been set on an altar and venerated by the public. But you can, at least, still marvel at the metalwork on display and the rock crystal insets on the object’s surface.

Where to find it: Medieval Galleries

Shrine of the Virgin, ca. 1300

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art When it is exhibited closed, this devotional object, known in its native Germany as a Schreinmadonna, looks modest, appearing to be little more than a plain sculpture of the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child suckling at her bosom. Once opened, however, it reveals its magic, showcasing a seated adult Christ surrounded by painted images of narratives from throughout his life. Such an unusual, beautiful object does not look out of place at a magnificent museum like the Met, but its original home may have been something humbler: a nunnery in the Rhineland region, where it would have been worshiped as part of a daily prayer ritual.

Where to find it: Medieval Galleries

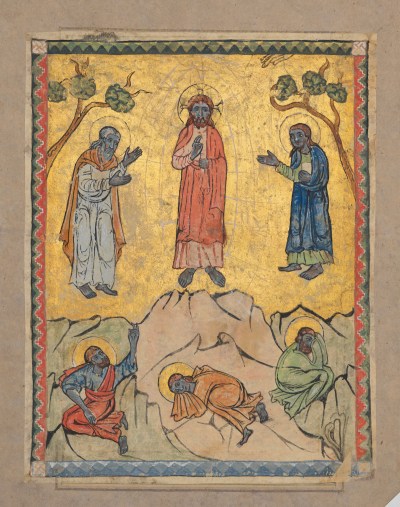

T’oros the Deacon, Transfiguration, 1311

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Whereas many Christian manuscripts at the Met feature white figures, this one is dominated by blue-skinned versions of Christ and his disciples—a hallmark of the manuscripts produced in Armenia by T’oros the Deacon during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Might T’oros the Deacon have based his beloved blues on the similarly hued sculptures of gods being produced by peoples located eastward? If so, his manuscript attests to the rich confluence of cultural influences found in Asia at the time, reworking centuries-old Christian imagery via the stylings of art coming out of China and Mongolia.

Where to find it: Medieval Galleries

Andrea della Robbia, Virgin and Child, ca. 1470–75

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Talent is sometimes said to run in the family, and that was certainly the case for the Della Robbias. Luca della Robbia gained a reputation for his terracotta sculptures, which were often glazed in rich shades of blue, and he clearly imparted some of his wisdom to his nephew Andrea, who built on Luca’s achievements in works such as this one. Andrea’s results were in some ways even more exquisite than his uncle’s: He left his figures entirely white, such that they contrast even more sharply with the blue glaze that acts as a background. Here the background is hardly static, however. The sculptor pictures God and a quartet of angels peering down from the clouds above, which Della Robbia represents as ridges that extend from the work’s surface.

Where to find it: The Great Hall

Giovanni di Paolo, The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise, 1445

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art If God forced you out of Paradise, how might you flee? Most would probably go in haste, and with no small amount of anxiety, but the Adam and Eve represented in this painting, originally part of an altarpiece for a Sienese church, leave Eden with little smiles on their faces—a strange flourish that suggests they are delighted by the knowledge they’ve obtained. In general, the painting is quite weird. (How can you miss the Creation narrative visualized to Adam and Eve’s left, in which an angel rolls along a boulderlike globe containing the zodiac, mountains, and more?) But weirdness ought not to be confused with poor quality, and the painting, with its lush blue skies and verdant lemon trees, is undeniably one of the more elegant treasures in the Robert Lehman Collection, a luxurious, sun-splashed area of the Met that looks like no other part of the museum.

Where to find it: Robert Lehman Collection

Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Carthusian, 1446

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Unlike their Italian peers, who relied on tempera, northern Renaissance painters such as Petrus Christus utilized oil paint to represent their subjects with a previously impossible level of detail—hence Christus’s ability to represent every scraggly strand of this monk’s beard, every long eyelash, every blond eyebrow hair. Christus appears to have been aware of just how real his image seemed and even played into it, painting onto this portrait an extraordinarily realistic frame that purports to show signs of wear. Etched into that painted frame, however, is a reminder that this object is an artwork, not the embodiment of a human being. “Petrus Christus made me in the year 1446,” it reads.

Where to find it: Robert Lehman Collection

Sandro Botticelli, The Annunciation, ca. 1485–92

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Unlike Botticelli’s two best-known works—The Birth of Venus and Primavera, both at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence—The Annunciation doesn’t announce itself as a masterpiece; it’s much smaller than those two other great paintings and much quieter, too. But what it lacks in visual drama, it makes up for in compositional flare, with Botticelli using one-point perspective to extend this sparsely decorated room back in space. Both the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary are shown kneeling on either side of a row of pillars that divides this room in two. Yet a divine emanation coming in through a window guides the eye across the partition, and Botticelli renders an otherworldly glow in lines formed from actual gold, causing the painting to gleam. The work, now located in the Met’s Robert Lehman Collection, may once have been used as a devotional painting; viewing it remains a spiritual experience.

Where to find it: Robert Lehman Collection

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, Princesse de Broglie, 1851–53

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’s almost invisible brushwork causes this portrait of a French aristocrat to look nearly photographic. The Neoclassicist painter highlights the sheen of her gold evening shawl and the lushness of her blue dress and asks us to imagine all the money that would have been spent acquiring clothes so refined as these. Fittingly, the painting was once held by a modern patrician, the banker Robert Lehman, who bequeathed most of his collection to the Met. The museum now hosts an entire wing dedicated to the bequest, with this Ingres painting acting as its crown jewel.

Where to find it: Robert Lehmann Collection

Attributed to Jean-Baptiste Voboam, Guitar, 1697

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Perhaps the Met will always be best known for its multitude of paintings and sculptures, and deservedly so. But its wing for musical instruments offers a compelling case study in how violins, organs, harpsichords, drums, and the like can also rise to the status of art when produced in particularly beautiful ways. Such is the case with this guitar, whose sides are inlaid with gorgeous, reddish tortoiseshell. Five strings would have originally run down this guitar’s neck, but with those strings now absent, one can get an unbroken glimpse into its ornate sound hole shaped like a star.

Where to find it: Musical Instruments Galleries

Duccio, Madonna and Child, ca. 1290–1300

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art In 13th-century Italy, Duccio started rewriting the rules of painting by pulling Christian subject matter down to earth, depicting biblical characters as though they were just as human as the rest of us. In this painting, he shows the baby Christ brushing the Virgin Mary’s veil to the side, effectively revealing her majesty to both himself and the viewer. Though mother and son are set against a gold-leafed background that appears removed from our world, Duccio also pictures them before a parapet similar to ones seen around Siena at the time—a detail that suggests they belong to the very same space as we do. In 2004 the Met paid a hefty $45 million to acquire the piece, making it one of the most expensive works ever bought by the museum. Not a penny was wasted.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Giotto di Bondone, The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1320

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Picking up where Sienese painters like Duccio left off, the Florence-based Giotto further pulled Christian subject matter down to earth by psychologizing each person he represented, suggesting that biblical figures were just as human as the rest of us. Note the attention to the caring gaze of the Virgin Mary, the ability to individuate each of the angels soaring above—these are trademark Giotto flourishes that made him one of the great painters of the pre-Renaissance era, and they’ve been taken up here by one of his followers. Painted for a Franciscan church, the work belongs to a series of seven highly valuable paintings narrating episodes from Christ’s life. Most of the remaining six reside in collections far beyond New York.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters, 1565

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Understandably, the grand Tiepolo painting that greets viewers entering the European paintings wing gets a lot of attention. But head just a couple galleries further in and you will find a true star in this plainspoken landscape. Like most of Bruegel’s finest paintings, this one situates a smattering of tiny figures—harvesters of hay in this instance—within a vast Flemish landscape. Bruegel lavishes attention on every laborer seen here: the ones hard at work cutting down hay, the ones tying it into shocks, the ones on break feasting beneath a tree. Off in the distance, there are yet more figures who play a ball game while the harvesters go about their jobs. They are tinier and harder to see than the harvesters, but the fact that they exist at all feels like a little miracle, a hint that an entire world exists beyond the frame of Bruegel’s picture.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

El Greco, View of Toledo, ca. 1599–1600

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Met owns so many topnotch El Greco paintings that it has devoted nearly an entire gallery to them. All of those works merit extended viewing, but the one that deserves special attention is this landscape, one of the two remaining paintings by El Greco that depict the Spanish city where he was based. As in his other paintings, the mood is dark, and nothing feels static. Trees, bushes, and entire hillsides appear to sway beneath cloudy skies; a cathedral and some accompanying buildings cling to the ground as if for dear life. This is decidedly not what Toledo actually looked like, of course, but rather a subjective perspective on the landscape. That may be why El Greco felt he had permission to disturb traditional notions of perspective. No surprise that El Greco gained a devoted fan in Picasso three centuries later.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

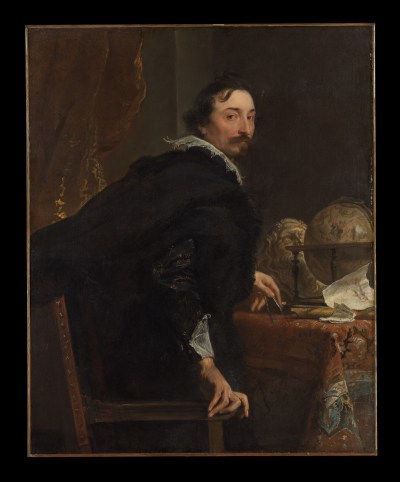

Anthony van Dyck, Lucas van Uffel, 1622

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Great portraitists can convey entire personalities in a single image, and Anthony van Dyck accomplished just that here. Lucas van Uffel was a Flemish merchant who amassed a significant art collection. Van Dyck presents his subject as a man of letters, casting him alongside a globe and some ruffled papers. But more than merely capturing Van Uffel’s worldliness, Van Dyck succeeds in portraying the intensity of his sitter’s psychology. Rather than depicting a seated Van Uffel, as so many other portraitists might have done, Van Dyck paints the precise moment that Van Uffel begins to scoot back his chair and rise from his desk. As he twists his body, his eyes meet ours, creating the sense that this patron is engaged in the same kind of deep looking that is essential for artists, critics, curators, and collectors across the world.

Where to find it: European Paintings Wing

Frans Hals, Young Man and Woman in an Inn, 1623

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Has there ever been a painter better at portraying drunkenness than Frans Hals? The Dutchman displayed his chops for that subject in works such as this one, in which an inebriated woman with flushed cheeks places an arm around a grinning man raising a glass. Their facial expressions suggest the kind of uninhibited joy often seen at parties, but this is not quite a bacchanal; their drinking spot is a sparsely furnished tavern adorned with just a couple of landscape paintings. Hals commonly represented spaces like this interior, which recognizably belongs to his time and place, and in doing so established himself as one of the great genre painters of the Dutch Golden Age.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Diego Velázquez, Juan de Pareja, 1650

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This Diego Velázquez portrait has been a beloved fixture of the Met’s European paintings galleries ever since the museum paid $5.5 million for it in 1971. But only recently has the painting’s sitter received due attention. He is Juan de Pareja, a painter who was born enslaved and was a member of Velázquez’s household. Pareja went on to work in Velázquez’s workshop, though Velázquez did not begin the process of freeing him until 1650. Velázquez’s portrait of Pareja has always been admired for its inky black background and the white strokes delineating where light hits Pareja’s skin (which Pareja himself portrayed as being darker in at least one of his works). But in 2023, when the Met staged a show specifically about Pareja, the painting gained new admiration as a crucial document of the racial tensions of its era.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1660

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Rembrandt was in his mid-50s by the time he painted this self-portrait, and his age shows—his eyes sag, his hair has gone gray, and his forehead has gained creases that were not there in previous self-portraits. Pictured against the brown background that recurs throughout the images he made of himself, Rembrandt casts himself as a painter of darkness who has begun to recede into it, perhaps because he knows he is approaching the later stages of his career. Ironically, the painting is just as notable for the ways that Rembrandt captures glimmers of light, with the tip of his ruddy nose catching so much illumination that it appears to shine.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Gerard ter Borch, Curiosity, ca. 1660–62

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Most of Gerard ter Borch’s paintings are unusually spare, with one or just a few figures set before mostly blank backgrounds, plus a few props to accompany his characters. The minimalism of his approach goes a long way, for it heightens the delicious—and deliciously underplayed—psychological drama of his tableaux. This painting takes its name from the nosy woman leaning over to get a look at a seemingly private letter being written by a female colleague. But what kind of letter is this, and who is its recipient? And who are these women, anyway? Ter Borch leaves those questions open, anticipating the similarly cryptic (and similarly sparse) works of later painters such as Édouard Manet, who would utilize the constraints of genre painting to needle accepted artistic conventions.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Johannes Vermeer, Allegory of the Catholic Faith, ca. 1670–72

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Picking a favorite among the five Johannes Vermeer paintings owned by the Met is an unfair task—they’re all great. But if you can spend time with just one, make it Allegory of the Catholic Faith, a painting that exhibits Vermeer’s flare for capturing light pouring into cloistered domestic spaces while also constructing a fascinating allegory. The allegory here concerns the value of piety, with the woman at the center acting as Faith personified. The painting abounds in visual rhymes: A sculpted crucifix mirrors a painting of Christ nailed to the cross, a curtain echoes the curve of Faith’s body, a glass orb mirrors the globe beneath Faith’s feet. In creating so many parallels, Vermeer suggests that one’s religiosity does not take place merely inside one’s heart or mind—it also informs an entire worldview.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Margareta Haverman, A Vase of Flowers, 1716

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art In recent years, the Met has begun placing due emphasis on previously overlooked female Old Masters, spotlighting rare and remarkable paintings that, in some cases, have spent years languishing in storage. But this still life is rarer than most of those other works, given that it’s one of just two extant paintings by Margareta Haverman, who worked in the Dutch Republic during the 18th century. Because of the painting’s title, we know there’s a vase somewhere beneath this cascade of blossoms, but the blooms are so extravagant that we can’t even see the vessel. In that way, it’s a shining example of still lifes of its era, which were sometimes meant as reminders of all that could be foraged in a world that was growing ever wider, in part because of Dutch colonial efforts abroad.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Antoine Watteau, Mezzetin, ca. 1718–20

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art It’s sad but true: the Met is not the best museum in New York for Rococo painting. (That would be the Frick Collection, which has Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s entire Progress of Love cycle.) Still, the museum does have a few gems related to the 18th-century French art movement, among them this Antoine Watteau painting of Mezzetino, a Harlequin-like stock character associated with commedia dell’arte. He’s shown here playing his guitar and singing forlornly, perhaps about a love interest who does not share his affection—Watteau poses him beside a statue of Venus, with her back toward Mezzetino. The painting is a standout example of Rococo art, whose pastel-colored meditations on ribaldry seduce viewers before denying them easy satisfaction.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Broken Eggs, 1756

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Even to contemporary eyes, it’s obvious that this painting is about more than just a basketful of cracked eggs and the young girl who was holding them; the work feels far more serious than the situation would merit. Back when Jean-Baptiste Greuze painted it, Broken Eggs would have been received as an allegory about virginity lost and innocence spoiled, hence the girl’s embarrassed look as she is castigated. Greuze was one of the great painters of genre scenes in 18th-century France; today, many of his moralizing messages feel dated. But even if Broken Eggs’s subject matter seems stodgy, his dynamic composition does not.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Not currently on view.

Unknown, Our Lady of Valvanera, ca. 1770–80

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Of all the great recent donations to the Met, perhaps the greatest was a 2018 gift of 10 paintings by Cuzco School artists, who translated Catholic styles derived from Europe for an Andean audience. Among them was this painting, which refers to a legend from Spain: A thief named Nuño Oñez was trying to pilfer goods from a farmer when he happened upon an angel, who revealed to him a sculpture of Our Lady of Valvanera in a tree. The transcendence of Catholicism now revealed to him, Nuño changed his ways and became a hermit; the painting depicts the seeds of that fervor being planted inside him. The astonishing canvas, filled with soaring birds and lined with gold leaf, recently made its debut in the European paintings wing, a sign that the Met has begun to acknowledge the ways that European styles extended far beyond the continent itself.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond, 1785

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Women seeking a career as an artist faced an uphill battle in 18th-century France, which is why Adélaïde Labille-Guiard trumpeted her success through this painting. That wasn’t an unusual theme in self-portraiture at the time. What was unusual was that Labille-Guiard pictured herself alongside two female students, both of whom are leaning in to learn from the painting she’s crafting. In 1971, in a landmark essay published by ARTnews, art historian Linda Nochlin would write on “the assumptions lying behind the question ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’” Two centuries earlier, Labille-Guiard took aim at those same assumptions—and suggested that great women artists have been with us all along.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Socrates, 1787

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Jacques-Louis David was one of the foremost artists of the Neoclassical movement, which revived the styles and histories of antiquity to extol rationalism and order. The Death of Socrates preaches these values by depicting the final moments of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, who held so strongly to his beliefs that he died by drinking hemlock instead of recanting them. The French painter’s composition—which is intentionally friezelike, recalling the imagery often seen on temples—swirls around Socrates, who acts like a stabilizing force and grounds the chaotic scene. David underplays the drama of the moment, relying on muted colors that don’t call attention to themselves.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Not currently on view.

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, ca. 1825–30

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Out of the Enlightenment grew the Romantic movement, which centered all that could not be approached with a rational mind: heightened emotion, mortality, invisible forces, and more. Caspar David Friedrich’s contribution to the movement generally took the form of awe-inspiring landscapes meant to move toward transcendence. That’s why, in this dusky scene, two men can be seen gazing at the moon, which here acts as a metaphor for the human life cycle. The German painter represented the men from behind so that viewers can imagine themselves staring out at this hilly landscape.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, 1852–55

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art To paint this epically scaled image of a horse market, Rosa Bonheur got up close to her subjects. Because women were barred from the markets and slaughterhouses that held these animals, she dressed as a man to gain entry. From those firsthand experiences, she was able to gain a sense of the musculature and anatomy of her equine subjects, to which she lent the same naturalism that she offered the other animals that appeared in her paintings. Hailed as a major work during its day, The Horse Fair exhibited Bonheur’s skill at psychologizing these animals while also showing off her flair for dynamic compositions. Here, a procession of horses appears to run out toward the viewer before galloping off into the background, an arrangement that recalls the way figures were sometimes laid out across ancient Greek friezes.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Édouard Manet, Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada, 1862

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Most come to the 19th-century painting galleries in search of lush Impressionist landscapes, but stop in front of this Manet painting first and behold it in all its conceptual knottiness. The painting depicts Victorine Meurent—the same model who appears in Manet’s Olympia—as a male espada, or bullfighter. Female bullfighters did exist at the time; Goya even depicted one in an etching that Manet used as an influence. But even so, Manet’s painting remained a provocation, a way of saying that fakery was inherently involved in genre scenes, which were for so long held up as a form of truth. The ground beneath Meurent’s feet appears to fade away, as though she stands on terrain that is literally unsettled.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Gustave Courbet, Woman with a Parrot, 1866

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Much like his fellow Frenchman Manet, Gustave Courbet shocked his viewers by taking up long-standing artistic conventions and twisting them in lurid ways. Having already gained a mixture of acclaim and derision through Realist paintings depicting lower-class models, Courbet here turned his attention to the odalisque. In the past, odalisques had generally been seductive, passive women who offered viewers a vision of beauty. Courbet’s odalisque, by contrast, appears to have torn off her clothes, collapsed onto a sheet, and begun playing with her pet. She is both an object of desire and a real person, and she angered more than a few viewers, with critics disparaging Courbet for capturing her hair in all its messiness. Courbet, whose work was perennially rejected by the Salon, characteristically seemed unrepentant, writing at the time that he was “still fighting” after all the adversity he faced.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

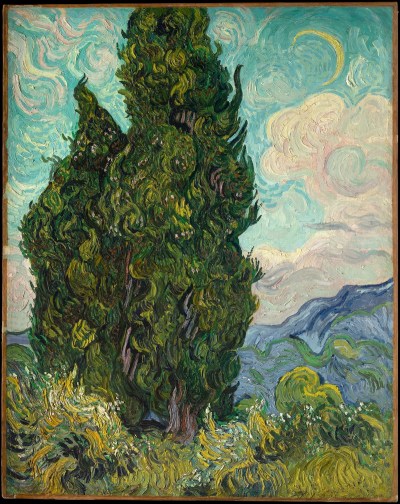

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses, 1889

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Though not necessarily the most famous Van Gogh in New York—that would be Starry Night (1889), at the Museum of Modern Art—Cypresses may be the best on hand in the city. The Dutch artist painted this work after checking himself into an asylum in Saint-Rémy, France, and noticing a cypress tree there. In Van Gogh’s rendition, the tree is just as roiled as his mind. Its leaves, rendered in his signature impasto technique, appear to spiral and warp, and so do the puffy clouds surrounding them. Van Gogh compared the cypress to an Egyptian obelisk. After viewing this painting, see how Van Gogh’s cypress stacks up against Cleopatra’s Needle, an actual ancient Egyptian obelisk permanently sited in Central Park, just outside the Met.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Claude Monet, The Four Trees, 1891

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Unlike Van Gogh’s cypresses, Claude Monet’s poplars tend to exude stateliness and serenity, standing tall even as nature around them changes. Indeed, quite a bit was shifting around the quartet of trees seen here. Monet painted them in Giverny, the French village where he produced some of his greatest works, and he very nearly couldn’t finish the work because local officials wanted to chop the trees down for sale. Monet, undeterred, paid to ensure that the sale wouldn’t happen until after his work was complete. With its smeary blues and speckles of yellow, the painting never quite comes into focus, suggesting that the quaint riverside scene was slipping free from Monet’s grasp even as he tried to render it permanent.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

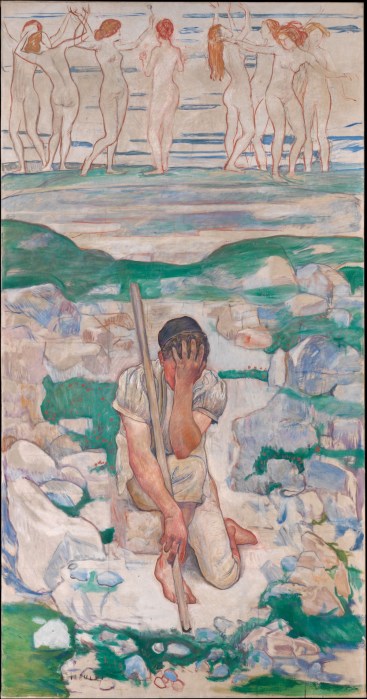

Ferdinand Hodler, Der Traum des Hirten (The Dream of the Shepherd), 1896

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Met’s 19th-century paintings galleries have historically leaned French, just like those of many other museums, but in recent years this institution has gradually turned its focus to artists from other European nations. Acquired by the Met in 2013, this painting by the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler is a recent addition to these galleries, and a welcome one, for its expressive coloration rhymes nicely with the hues of Impressionist works found here. Hodler’s painting depicts a napping shepherd and the vision he dreams up: eight nude nymphs dancing above the mountains around him. The eight-foot-tall painting is downright strange, if not solely for its overt psychosexuality, then also for its flattened perspective and its unresolved landscape. Note the way the rocks appear to fade away altogether, leaving behind blank canvas.

Where to find it: European Paintings Galleries

Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, ca. 1478–82

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Nestled in a hard-to-find corner of the Met just beyond its Great Hall is one of the greatest rooms found anywhere in the museum: the study, or studiolo, from the palace of Federico III da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino. The contents of this room once belonged to an even larger space at the ducal palace, but even in its abbreviated form, this study stuns. Its walls, elegantly composed by Giuliano da Majano via a wood inlay technique known as intarsia, trick the eye by creating the illusion that a range of objects—an hourglass, a bird in a cage, a pipe organ, and much more—have been placed within opened cabinets that do not actually exist.

Where to find it: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Galleries

Patio from the Castle of Vélez Blanco, 1506–15

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Parts of this patio were already a long way from their home in Andalusia, Spain, before arriving at the Met: The collector George Blumenthal had already purchased the patio’s marble fittings, exhibiting them in his New York residence before they entered the Met via his bequest. That bequest also allowed the Met to acquire 2,000 more marble elements to complement those fittings, and now the fruit of all that labor is on display in an airy two-floor space off the Great Hall, where one can find the balconies, timber ceilings, and Gothic gargoyles as they once appeared at the Castle of Vélez Blanco. Beneath those balconies, the Met regularly exhibits first-class examples of Baroque sculpture, including one exquisite bacchanal scene crafted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Where to find it: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Galleries

Orpheus Cup, ca. 1600, 1641–42

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The Met’s extensive European decorative arts holdings tend to get short shrift from the public. How unfair! Works such as this one demonstrate why all the lavish drinkware, furniture, miniatures, and more featured the department’s galleries deserve more attention. The Orpheus Cup, as this object is known, is centered on the familiar figure of Orpheus, a musician from Greek mythology. But this representation of him, as envisioned by Jan Vermeyen’s Prague Imperial Workshop, is anything but average, since it is accompanied by a profusion of enameled dogs, rabbits, and nude people, some studded with rubies. The staggering level of detail even extends to the lizards and frogs at Orpheus’s feet, climbing out of the water to admire him.

Where to find it: European Sculptures and Decorative Arts Galleries

Giovanni Francesco Susini, Hermaphrodite, 1639

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The discovery of a Roman sculpture of an intersex individual in 1619 triggered an interest in the mythological figure of Hermaphroditus among 17th-century Italian sculptors, with Gian Lorenzo Bernini even making a marble mattress to go under the ancient statue. (The Bernini mattress, along with the ancient statue itself, are held by the Louvre.) Giovanni Francesco Susini then made his response to Bernini in the form of this bronze sculpture, in which Hermaphroditus reclines on an even more elaborate bed. Hermaphroditus is shown turning over in his sleep, twirling the sheets around his legs in the process. Susini’s bronze casts were prized during his day and continue to intrigue contemporary audiences—the designer Yves Saint Laurent even owned one.

Where to find it: European Sculptures and Decorative Arts Galleries

Balthasar Permoser, Marsyas, ca. 1680–85

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art According to Greek mythology, the satyr Marsyas suffered a bitter end when he challenged Apollo to a music-playing contest, only to be outdone by the god and then flayed as a punishment for his hubris. (Poor Marsyas!) Rather than representing the contest, sculptor Balthasar Permoser depicts Marsyas undergoing his brutal punishment—not by showing the act of violence itself, but by offering the satyr’s face contorted into a scream. As he twists his head to one side, Marsyas’s wrap also appears to turn. It’s as vivid a depiction of pain as they come, and Permoser’s approach to it embraces the stylings of Baroque art, which emphasized visual drama and heightened emotional states.

Where to find it: European Sculptures and Decorative Arts Galleries

Johann Gottlieb Kirchner, Lion, ca. 1732

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art In 1710 the Meissen porcelain manufactory in Dresden began producing figurines and tableware that were much sought-after. Augustus II the Strong, the Elector of Saxony, was one of its leading financers, and at his behest, chief manufacturer Johann Gottlieb Kirchner started making life-size porcelain versions of animals for a menagerie to be housed in Augustus’s Japanese Palace. This model for one of those animals shows off Kirchner’s knack for portraying the psychology of his mammalian subjects, with this lion’s furrowed brows causing him to appear sad instead of vicious.

Where to find it: European Sculptures and Decorative Arts Galleries

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Why Born Enslaved!, 1868/73

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Some of the most thrilling curatorial work conducted by the Met in recent years has involved reappraising much-loved works such as this one. Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s bust, the subject of an entire Met show in 2022, was treated as an abolitionist icon during its day, when its viewers saw it as a passionate call for an end to enslavement. But the work is more complicated than that: France had outlawed slavery roughly two decades earlier, and Carpeaux seemed to sexualize his Black female subject, showing her breasts spilling out between the ropes that bind her. Why bother looking at Why Born Enslaved!, then? Because the work offers crucial insight into how 19th-century Europeans thought about enslavement as it was finally being abolished—and shows how well-intentioned artworks can negatively shape the debate around the topics they protest.

Where to find it: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Galleries

Joshua Johnson, Emma Van Name, ca. 1805

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Most visitors to the Met’s wing for American art come seeking portraits of presidents past and Hudson River School landscapes—more on those soon. But some of the greatest works here don’t fit neatly into any category. Emma Van Name is one of those works. It’s the most well-known painting by Joshua Johnson, who is commonly regarded as one of the first Black artists in the United States, and its strawberry-loving Maryland toddler helped define a folksy aesthetic that feels distinctly American, with a flat background and a delectable weirdness. (Why is that goblet filled to the brim with fruit? Don’t ask too many questions.) Though the portrait is beloved today, the Met is actually the second New York museum to own it. The first was the Whitney Museum, which sold it during the 1980s, prompting vocal protest from such high-profile figures as the actor Bill Cosby.

Where to find it: American Wing

Headdress Frontlet, ca. 1820–1840

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Shimmering abalone shell provides the background for this headdress, which would have been worn during ceremonies held by the Tshimshian people of British Columbia. Between all that abalone are heads carved from wood, with one lent a pointy bird’s beak. That face is emblematic of the imaginative ways that Tshimshian artists use their work to visualize humans who have fused with nature, forming new hybrids in the process. This headdress, which entered the Met’s collection in 2019, is now a highlight of the American Wing, which has only recently begun to emphasize the contributions of Native American artists.

Where to find it: American Wing

Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, After a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, 1836

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This view of rain clouds departing the Connecticut River Valley is so stunning that you’d be forgiven for failing to spot its lone human: Thomas Cole himself, who can be seen painting on a cliff in the foreground. The lack of obvious figures is both a feature and a bug. On the one hand, it makes this painting, an iconic work of the Hudson River School movement, all the more sublime, allowing one to bask in the beauty of the river’s U-shaped bend, the surrounding foliage, and the looming mountains, whose grassy surfaces Cole depicted as being largely undeveloped. On the other hand, in choosing not to represent the Native Americans who populated lands such as these, Cole committed a form of erasure that contemporary Indigenous artists are still contending with. In 2020, for example, Kay WalkingStick, a Cherokee artist who is also of European descent, repainted The Oxbow, overlaying part of it with Pocumtuc symbols.

Where to find it: American Wing

George Caleb Bingham, Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, 1845

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This famed painting is now known by its defanged title; George Caleb Bingham had himself labeled it French Trader & Half breed Son before its initial exhibiting institution altered it. Bingham’s original title laid bare something that is just barely hidden beneath the painting’s placid surface: America’s rapidly expanding economy was fraught with racial tension. But if you took just a quick look at the painting and stopped only to admire the kitty leashed to the prow of the canoe or the rippling waters all around it, you might not notice anything amiss. The contrast between a peaceful American vista and the hot-button political issues appended to it is one of the things that make this painting so fascinating (and tough) for contemporary eyes.

Where to find it: American Wing

David Drake, Storage Jar, 1858

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art The South Carolina town of Edgefield is not exactly a tourist attraction, but those versed in America art history know it well, for it was once a site where enslaved people produced pottery inscribed with messages obliquely alluding to their dispossession. David Drake crafted some of those memorable vessels, including this stoneware jar once used for storing food. Written into the work is a message that reads, in part, “when you fill this Jar with pork or beef / Scot will be there; to get a peace”—words that anticipate the freedom Drake would himself obtain by the end of the Civil War. Drake signed the work with his artistic moniker, Dave—an assertion of his existence during a time when many Americans would have refused to acknowledge his personhood.

Where to find it: American Wing

Frank Waller, Interior View of the Metropolitan Museum of Art When in Fourteenth Street, 1881

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Nestled in the American Wing is this reminder of the quaint museum the Met once was before it became the behemoth it is today. The American painter Frank Waller here pictures the Met as it existed when housed in a mansion on 14th Street. Back then, the paintings were hung salon style, and the displays—at least as Waller represented them—were more modest. But it’s nice to recall the Met’s past and play it against its present. Henry Peters Gray’s painting The Wages of War (1848), the work visible here above the doorway, is still on view at the Met not far from Waller’s canvas.

Where to find it: American Wing

John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau), 1883–84

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art This painting was a succès de scandale at the 1884 Paris Salon, where pearl-clutching critics and the public alike reacted with bile to its overt sensuality. John Singer Sargent, apparently anticipating this response, concealed the name of its subject: Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, an American socialite who had French Creole ancestry. And when he finally sold the painting to the Met, Sargent even asked the museum to continue to hide Gautreau’s name, which is how the work earned its moniker of Madame X. But time has since redeemed this painting, which is justly regarded as a landmark work of its era—a necessary test of bourgeois sexual norms that anticipated even racier works to come.

Where to find it: American Wing

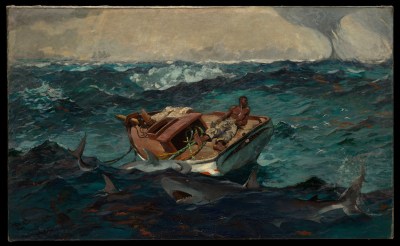

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Many of Winslow Homer’s paintings were daring in their day—they represented political issues explicitly, without pulling any punches. The Gulf Stream is tough to read as anything other than an allegory for the state of Black life in the United States at the time, when the Civil War was still only a few decades in the past. A Black man can be seen resting in a boat amid unsettled waters. There is danger all around: Sharks leap out of the water in front of him, and a storm seems to follow him. But this man looks resigned and unconcerned, perhaps having accepted the treacherousness of his situation. Homer’s image is so timeless that artists keep returning to it; Kerry James Marshall, for example, revisited The Gulf Stream in 2003, envisioning several Black seafarers sailing along waves that are much more placid.

Where to find it: American Wing

Mary Cassatt, Young Mother Sewing, 1900

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art As women artists have long recognized, housework is work. So it is hardly surprising that, in 1900, roughly six decades before the start of the modern feminist movement, the American Impressionist Mary Cassatt painted a mother sewing with such concentration that she doesn’t even acknowledge the little girl on her lap. The scene is peaceful: Outside, light splashes across a grassy lawn, and inside, orange flowers bask in the sun. But this mother notices none of it, for she focuses only on the task at hand. Her unsentimental gaze seems at odds with the elegance of Cassatt’s alluring pastel colors.

Where to find it: American Wing

Tiffany Studios, Garden Landscape, ca. 1905–15

Image Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art Only at the Met can you find not one but several stained-glass windows produced by Tiffany Studios. A three-part window acquired in 2024 is the biggest, and an autumnal scene added to the collection nearly a century earlier is the lushest. But Garden Landscape is certainly the most extravagant of the bunch—it has a functional fountain in addition to mosaics depicting swans, cypress trees, and an overflowing bouquet. Made using the favrile glass that became Tiffany Studios’ calling card, the window’s iridescent tesserae catch the soft light that bathes the atrium of the American Wing.

Where to find it: American Wing

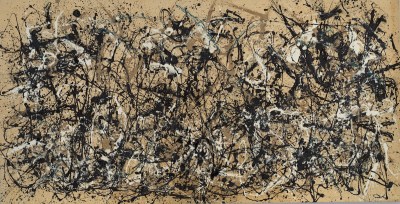

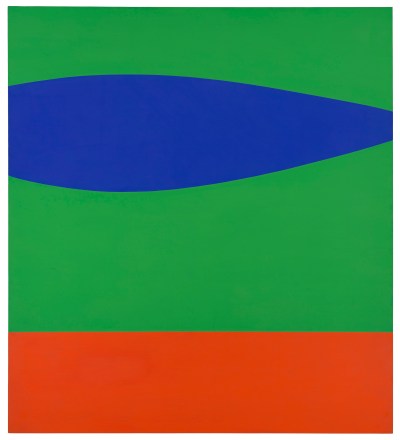

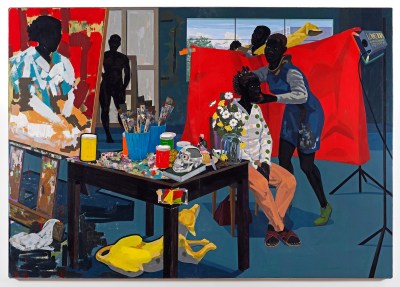

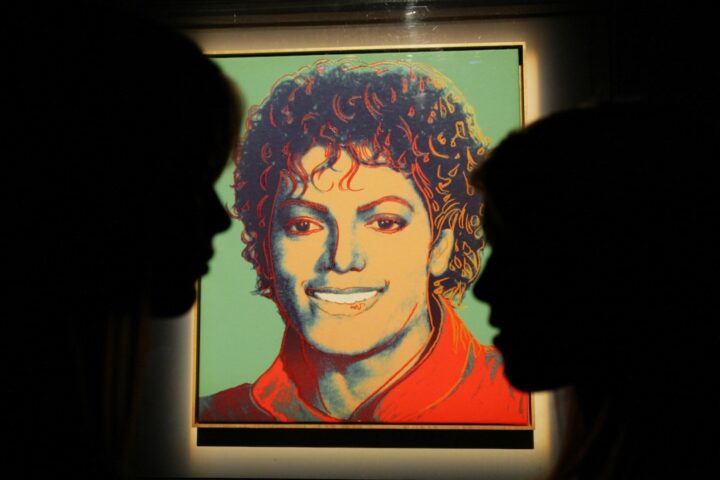

Frank Lloyd Wright, Living Room from the Francis W. Little House, 1912–14